Sacred Streams: Awareness and Intentionality in Druidry

NEW YORK – It was 1 p.m. in New York City and 6 p.m. in the United Kingdom, when Nick Gent, 44, a Druidic sound healer, began his virtual Druidry class on Friday, Feb. 2. The class was small — just one woman from Connecticut signed on — so Gent started right away.

The class, called Practical Druidry, was one of a series that Gent offers online. Though he encouraged reading books and other materials to learn about Druidry, the lessons he teaches in his class are from his lifetime of practical experience.

“I have always known the world to be alive and full of magic,” Gent said later.

Druidry is a spiritual practice and one form of neo-paganism that focuses on having a relationship with the natural world. Druidry is often practiced alone, but there are also groups of Druids around the world who do ceremonies together.

There is no definitive number of people who practice Druidry, but one of the largest Druid groups — the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, based in the U.K. — has more than 30,000 members in 50 countries.

Gent, from London, is a musician and has been a sound healer for over a decade. He has also been a druid his whole life. He offers one-on-one sessions for teaching Druidry, as well as his weekly Practical Druidry classes, which don’t often get a huge turnout. The people who do show up are typically from Europe and the U.S.

In this particular hour-long class, Gent talked his student through what he called the 10 mirrors of Awen, a step-by-step process to help someone see their own mind clearly and then relate to the external, natural world.

Each of the 10 steps involved a visualization, a three-syllable sound and breathwork, all guided by Gent. The second step, “the mirror of stream,” was about becoming aware of one’s emotions. Gent led his student to close her eyes and visualize herself walking by a clear, flowing stream.

“Each ripple, perhaps, could represent for us an emotion, arising from the depths and then naturally flowing on its path,” Gent said. “Here, the idea is to observe how the ripples form, travel to the water’s surface and then fade away, just like the natural flow of the emotions within us.”

Like a stream allows waves to pass through it, Gent encouraged his student to accept and understand her emotions, rather than try to change or resist them.

Gent then made a humming sound to follow the visualization, a sound he said he made up.

“The actual sound itself doesn’t matter,” he said.

Instead, what matters is the intention behind the sound.

“You can use any sound that feels right to you,” he said. “We can embed our intentionality, or consciousness, if you’d like, to some degree, on the waveform.”

Later in the class, Gent explained the significance of flowing water.

“In Druidry, in a practical sense, streams and rivers are very much seen as sacred,” Gent said.

“They symbolize life, healing, purification, the passage of time, the cycles of the earth, on a physical level. But the stream, like we just talked about, is also a metaphor for the flow of emotions, thoughts.”

As the class came to an end, Gent encouraged his student to practice the skills and concepts from the 10 mirrors and to integrate them into her daily practice, or in daily life.

“The lesson of the water is to help you navigate those thoughts and emotions, but also to understand how you might be able to manage them, using the principle of flowing, the natural flow,” Gent said.

“Let Everything That Has Breath Praise the Lord”: Chanting in the Orthodox Church

BROOKLYN — The Divine Liturgy at St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral in Brooklyn on a recent rainy Sunday morning overwhelms the senses. Incense hangs heavily in the air, and the icons are everywhere, painted on the walls and the ceiling. Sacred relics are set aside for viewing. Candles decorate the whole space. There are yellow candles in the back for parishioners to light. The red candles in front of the icons at the front of the sanctuary. There are rows of light wooden pews, but most people are standing. The chanting has already begun to the left side of the nave.

St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral is located at 355 State Street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. It’s an Antiochian Orthodox Church. The stone church was first built as an Episcopal church in the 1850s. It was made in the Gothic style with high arches. It became an Orthodox church in 1920. On Sundays, Matins is sung before Divine Liturgy begins at 10:30.

The liturgical chanters are primarily men, a single woman in their midst. They stand in a circle, surrounding a music stand with a golden cross at the center. Some men have iPads and others have sheets of paper. For the most part, they sing alone. The congregation does not sing along. The chanters go back and forth between English and Arabic. Dressed in shades of navy and black and gray and cream, their voices are deep. “Praise Him. Let everything that has breath praise the Lord,” they sing. As congregants enter the church, the chanters’ words are there to greet them. The chants are responsorial. The priest and the chanters are in conversation, and the congregation are the witnesses.

Among the chanters is George Zain. Five years ago, Zain started taking chanting lessons with a priest. He took lessons once a week for three years. Most of the men in the choir have classically Western backgrounds, but Zain favors the Byzantine style. For him, the Western style is more analytic, but with the Byzantine chanting, he said, there is more room to elaborate. “The beauty is you can play with it more.” He sings words like “Resurrection” and “Light,” and gestures upwards. But other words like “death” and “Hades,” he says, “it’s more chromatic, it’s down here.” The liturgical songs are meant to go beyond understanding, and directly engage your heart. There is a mystical quality to it.

Zain feels keenly his responsibility as a liturgical singer, recognizing he has had times where he would sing the words but his heart wasn’t engaged. He feels strongly that the chanting is best done, not with the most pleasing voice, but with an engaged spirit that feels deeply what they are saying. The purpose of liturgical songs is clear to him: “it’s to transcend the faithful, edify the faithful.”

The songs aren’t something you have to understand. “The musician can still speak to you even if you don’t understand. The text, it can transcend body and soul.” Chanting is a crucial part of the Orthodox service, a service that is all about the senses, according to Zain. The rich incense, the gold, the iconography, the chanting—the body is engaged so that the heart can be reached.

Desire for God: A Teaching on the Story of Zacchaeus

NEW YORK — The Rev. Thomas Zain of St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church in Brooklyn faces his congregation as the choir sings, “Intercede with Christ, He will save our souls.” Everyone is standing. A letter from Scripture is sung by one of the chanters after which, Zain sings, “The Holy Gospel” and makes the sign of the cross. The congregation does the same. Zain chants from the Gospel of Luke, the story of Zacchaeus.

St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral is located at 355 State Street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. It’s an Antiochian Orthodox Church made in the Gothic style.

The gospel tells of how Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector in the city of Jericho and a man of short stature but of pure faith, climbed a sycamore to see Jesus. When Zain finished reading, he made the sign of the cross, indicating the end of the gospel and the beginning of the teaching.

Zain first makes mention of the upcoming season of the church, Lent. The story of Zacchaeus’s climb up the tree, he jokes, is “a nice way to say he was short,” bringing a light tone to a more introspective story. Zacchaeus, he said, “desired to see God” and went to great lengths to witness Jesus in the crowd.

Zain invites the congregation to meditate and imagine themselves in a crowd longing to see something or someone. “He desired to see Christ so much.” He is urging the congregation to consider their desire to see Christ in their own lives. “Everything we want to do in this life begins with desire.”

Zain has notes in his hands, but mostly speaks unaided. He wants to make sure the parishioners are inspecting their own hearts, and prompts them with a question: “What do we really love and desire more than anything else?” He references a meme about people in the cold watching a football game and compares it to the struggle of making it to church, whether it’s the cold or being unable to find parking. He pauses. This invites the listener to take stock of their spiritual habits.

“Zacchaeus is an example, brothers and sisters, for all of us,” he says. References to “we” and “us” let the parishioner know that Zain struggles himself, despite being a priest.

“Imagine that if God said I want to come and eat in your home,” the priest says. He engages the imagination using the gospel story. “We have to let Him in, and it begins with desire.” Zain refers to the idea of God living in people versus having worldly desires that push Him away. Worldly desires, he says, are “those things [that] fill our hearts and there’s no room for Christ.” He pauses again, providing a moment for the parishioner to examine their hearts. He moves onto this idea of cleansing oneself to make room for Christ, and that it begins with desire. He glances at his notes and references Revelation, “Behold I stand at the door and knock.” Christ is the one who knocks at the door in our hearts.

Zain’s voice grows louder to emphasize, “Today salvation has come to this house.” Zain wants his congregation to realize they can only respond to Christ when their desires are pure. Then we can hear His knocking on our hearts. He sends by saying, “Let us take this lesson with Zacchaeus and ask ourselves ‘what is our desire?’ That we may one day be worthy of the kingdom.” He ends with the sign of the cross, and the congregation does the same.

Becoming an Adult at Temple Emanu-El

NEW YORK - “We are on the corner of Fifth and 65 Street in 2024. But now, we are going back to Mount Sinai,” Rabbi Sarah Reines said from the pulpit of Temple Emanu-El during a Shabbat service.

For at Mount Sinai, said Reines, Moses received a sacred scroll that would be passed down through the generations.

This was the cue for 13-year-old Gavin Matlin, who up until this point had been sitting in a chair to the right of the ark, wearing a suit and a tallit, his feet dangling a few inches above the floor. Gavin stood and moved to the front of the bimah.

Reines pulled open the doors of the ark and retrieved the Torah while Gavin’s family — his sister, parents and grandparents, all dressed in trim black suits and dresses — ascended the stairs to the bimah and lined up next to him.

“This is the Torah, a light for our eyes, a lamp for our way,” sang the congregation.

“Our ancestors roamed that desert so many thousands of years ago and they were given this great gift,” Reines said, carrying the Torah scrolls wrapped in a mantle of red velvet with gold tassels. “And you are all here now because someone in your family line loved Judaism and loved their children enough to pass on this gift. Gavin, now it comes to you.”

Reines presented the Torah to Gavin’s grandfather, who, in a sign of veneration, extended a hand to grasp the velvet mantle. Reines stepped forward to the boy’s grandmother, who did the same. The rabbi walked down the line of family, pausing so that each member could touch the Torah.

And so, from generation to generation, the Torah was handed down to Gavin on his Bar Mitzvah.

When the scrolls reached Gavin, he seemed to take in the weight of all that was wrapped in the mantle before him — physically, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible are contained in the scrolls, but in a broader sense, Jewish law and tradition and Matlin’s responsibility to the Jewish community are also there.

After a moment’s pause, he reached out to touch the mantle, before turning and springing toward his sister in a hug.

The boy, a boy no longer in Jewish eyes, embraced each member of his family and walked side by side with Reines to the pulpit, where he read a Torah portion from the Book of Exodus and gave a short speech. Reines then welcomed him as an adult member of the congregation.

Besties in Biblical Times

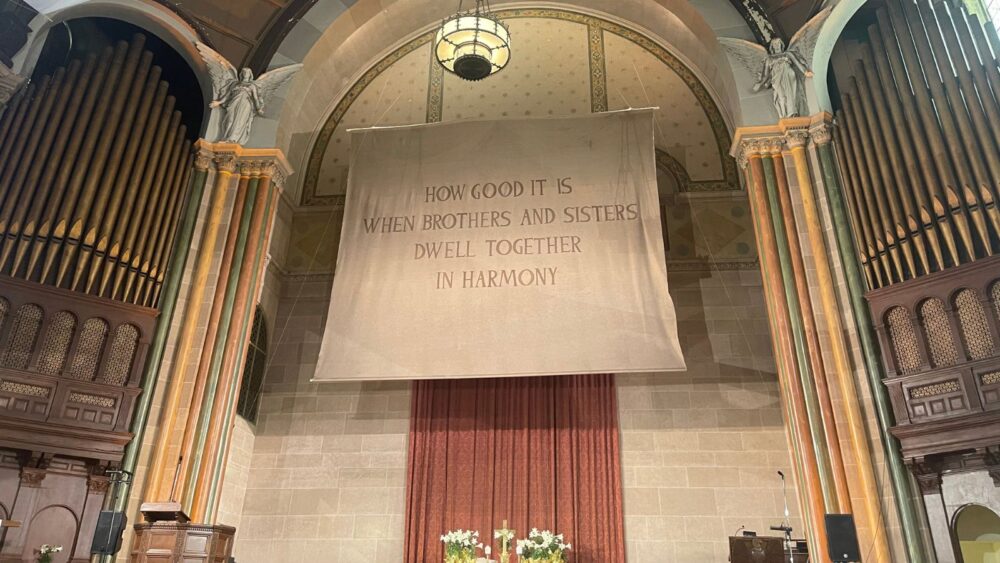

NEW YORK – Between two Christian spirituals, a rowdy group of seven kids run onto the stage during Sunday morning service at St. Paul & St. Andrew United Methodist Church on 86 Street on the Upper West Side.

A boy with a shaved head in a pink button-down takes the microphone and tells the congregation that he is going to his friend Jonah’s birthday party later that day. A coy girl in gingham with a long ponytail says her best friend Sophia always gives her presents. The congregation giggles.

However, the children’s chatty irreverence is not an interruption to the service. It’s time for the "Messages for All Ages" portion, during which the congregation’s youth and campus pastor, Ekama Eni, leads the children in a lesson before they head to the chapel for Sunday school. She teaches by example.

“I want to tell you about someone,” Eni says, leading off the message from the stage. She shows the children a photo of her friend Sam. “We cook together, we study together, we go to drag shows together. Would anyone like to tell me about their best friend?” What follows keeps the adults engaged, while the kids appreciate Eni saving them from the boredom of sitting quietly in a pew.

Eni tells the children that the Gospel reading they will hear while walking to Sunday school is about a man who is not feeling well and his four “besties.” The "besties" have heard that Jesus makes people better so they are going to take their friend to see him.

Theatrically retelling the story of Mark, chapter 2, when Jesus heals a paralyzed man, Eni says that the house where Jesus was at the time was very crowded, so the friends climbed onto the roof, cut a hole in the ceiling, and lowered their best friend into the house to see Jesus.

“That is dedication to being a bestie,” says Eni.

She emphasizes the importance of friends, those they can giggle with and do incredible things with, because Jesus loves them.

Eni, 30, graduated from Union Theological Seminary in 2021. She says that her approach to teaching kids is to invite mutual curiosity.

“I'm obsessed with the minds and thoughts of children,” she says after the service. “I'm always going to try and engage them most importantly as fellow human beings with thoughts and feelings.”

For Eni, it’s about making children feel like a part of the larger church community.

“Dear God, thank you for besties,” Eni says as she notices the children starting to get antsy. “Amen.” And the children scramble off to the chapel.