Music as a Medium to Engage Young People in Church Life

DUBLIN — A recent Youth Mass at St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral in Dublin started with a song that seemed to fit better in an evangelical worship service than among the Catholic rituals. A five-piece band led the congregation in an upbeat version of “Blessed be the name of the Lord, Blessed be Your Name.”

The next day at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral, part of the Church of Ireland, a choir from the University of Richmond sang Sanctua, Oread Farewell and the Irish Blessing. A few miles away at Our Lady of Victories, primary school students dressed in plaid were practicing songs for their concert Emmanuel 2024. In an informal homily, they were encouraged to keep singing.

After the Youth Mass at St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, in the Oratory, a group of young adults, and on occasion a few older folks, gathered together in a circle, and after introductions began to sing. The community is called Shalom Dublin. It’s based on the original Shalom Catholic Community from Brazil. People were drawn into Shalom by its charismatic qualities of speaking in tongues or by the spontaneous worship music.

The sounds of music are everywhere these days in Dublin’s churches. While rates of religious affiliation are rapidly dropping in Ireland, the music continues. Church leaders believe that music can touch young people and keep them open to exploring faith.

Music is what drew Mirielle Abreu, 39, deeper into the Catholic community. Abreu is one of the singers in the band at the Shalom community in Dublin. Originally from Brazil, she found herself going to Shalom after a friend invited her. In 2016, while she was working in Brazil as an actress, she had a back injury. “And I thought: I cannot dance, I cannot act because of my back. I think I’m gonna sing and I would like to sing to the Lord, and I started.” She moved to Dublin in 2022, and has continued to sing.

In her experience, Shalom focused a lot on the youth. “They are the generation, they are the future,” Abreu said. She sang a song in Portuguese to demonstrate. The lyrics translate into “I want to offer my life and spend my days for love, for the church, for the youth.” A lot of the songs sung at Shalom Dublin were written at songwriting retreats by Shalom members. “In Brazil, every single church that you go, they are singing Shalom songs,” Abreu said.

In the Oratory, the room was dim except for the two candles lit at the front. Music missionary and co-founder of Shalom Dublin, Meggie Teixeira Correa and Leon Dominic Thomas, two of the other singers in the band, sang Ruah (translated to God’s Spirit), a Shalom song. The words were repeated over and over again. “Come Holy Spirit, inflame our hearts, Kindle in us the flame of your life. Come and renew us by the power of your love,” mirroring the Catholic prayer, “Come, Holy Spirit.”

Abreu noted that some of the things that weren’t common to others, like speaking in tongues, were familiar to her from her upbringing in Brazil. For her, Shalom is just “one way of being close to God. It’s a family.”

Another Shalom Dublin regular, Olivia Lívia Alencar, 23, recognized that people enjoyed the singing at Mass on Sunday nights. She recalled an elderly lady saying, “That was a beautiful ministry.” Olivia got to know Shalom in Rio after her best friend invited her to a prayer group. Many of the people at Shalom Dublin were foreigners, from different parts of Europe, and the charismatic element of the group was new to them, Olivia said.

Music is also a focus of Catholic efforts to reach the youth. One of the composers of contemporary Catholic music is Ciaran Coll, a music teacher at one of the schools that participated in Emmanuel 2024, the contemporary liturgical concert. Emmanuel is a big event, spanning three days and over 2,000 students all over Dublin. Coll has composed some of the pieces performed at Emmanuel the past five years. As a teacher, he teaches his students songs for the concert from early September to February. “If young people weren’t engaged in liturgy and the church or going to church, this was a way in that appealed to them,” said Coll.

At Catholic schools, events such as the first mass of the year and school graduations that revolved around the Eucharist needed music, but teachers were relying on secular music to reach their students. Emmanuel provided students with a greater variety of music, drawing on both traditional hymns and contemporary liturgical music. “I’ve seen, over the last number of years doing it, that students love the music so much that when it comes to school masses or graduation, they’re reaching for their Emmanuel book,” said Coll.

Coll led one of the practices for Emmanuel 2024 the afternoon before the concert, playing the piano as students sang “Amen.” The main goal with having students join groups or audition for a solo for Emmanuel is to open students to a wider world of what church music is really like and to engage them in the school setting. “By doing this, you have a group of students who are there and available to then hear from somebody, to have somebody to speak to them, to do a short reflection or homily with them,” he said.

Participating in the act of creating music with their classmates can also make them curious for more. That curiosity could trickle into other areas. “It may bring them to a deeper connection that they want to seek a little bit more and ask a few questions of their faith,” said Coll.

Coll has learned a lot about teaching his students liturgical music over the last five years. He strives to keep students engaged by choosing songs they like. "Is there a buy-in from them? Will it speak to them?" he said he asks himself. "And so, I think, it’s about listening to them and being open to see what really touches their hearts.”

“Let Everything That Has Breath Praise the Lord”: Chanting in the Orthodox Church

BROOKLYN — The Divine Liturgy at St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral in Brooklyn on a recent rainy Sunday morning overwhelms the senses. Incense hangs heavily in the air, and the icons are everywhere, painted on the walls and the ceiling. Sacred relics are set aside for viewing. Candles decorate the whole space. There are yellow candles in the back for parishioners to light. The red candles in front of the icons at the front of the sanctuary. There are rows of light wooden pews, but most people are standing. The chanting has already begun to the left side of the nave.

St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral is located at 355 State Street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. It’s an Antiochian Orthodox Church. The stone church was first built as an Episcopal church in the 1850s. It was made in the Gothic style with high arches. It became an Orthodox church in 1920. On Sundays, Matins is sung before Divine Liturgy begins at 10:30.

The liturgical chanters are primarily men, a single woman in their midst. They stand in a circle, surrounding a music stand with a golden cross at the center. Some men have iPads and others have sheets of paper. For the most part, they sing alone. The congregation does not sing along. The chanters go back and forth between English and Arabic. Dressed in shades of navy and black and gray and cream, their voices are deep. “Praise Him. Let everything that has breath praise the Lord,” they sing. As congregants enter the church, the chanters’ words are there to greet them. The chants are responsorial. The priest and the chanters are in conversation, and the congregation are the witnesses.

Among the chanters is George Zain. Five years ago, Zain started taking chanting lessons with a priest. He took lessons once a week for three years. Most of the men in the choir have classically Western backgrounds, but Zain favors the Byzantine style. For him, the Western style is more analytic, but with the Byzantine chanting, he said, there is more room to elaborate. “The beauty is you can play with it more.” He sings words like “Resurrection” and “Light,” and gestures upwards. But other words like “death” and “Hades,” he says, “it’s more chromatic, it’s down here.” The liturgical songs are meant to go beyond understanding, and directly engage your heart. There is a mystical quality to it.

Zain feels keenly his responsibility as a liturgical singer, recognizing he has had times where he would sing the words but his heart wasn’t engaged. He feels strongly that the chanting is best done, not with the most pleasing voice, but with an engaged spirit that feels deeply what they are saying. The purpose of liturgical songs is clear to him: “it’s to transcend the faithful, edify the faithful.”

The songs aren’t something you have to understand. “The musician can still speak to you even if you don’t understand. The text, it can transcend body and soul.” Chanting is a crucial part of the Orthodox service, a service that is all about the senses, according to Zain. The rich incense, the gold, the iconography, the chanting—the body is engaged so that the heart can be reached.

Desire for God: A Teaching on the Story of Zacchaeus

NEW YORK — The Rev. Thomas Zain of St. Nicholas Antiochian Orthodox Church in Brooklyn faces his congregation as the choir sings, “Intercede with Christ, He will save our souls.” Everyone is standing. A letter from Scripture is sung by one of the chanters after which, Zain sings, “The Holy Gospel” and makes the sign of the cross. The congregation does the same. Zain chants from the Gospel of Luke, the story of Zacchaeus.

St. Nicholas Antioch Cathedral is located at 355 State Street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. It’s an Antiochian Orthodox Church made in the Gothic style.

The gospel tells of how Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector in the city of Jericho and a man of short stature but of pure faith, climbed a sycamore to see Jesus. When Zain finished reading, he made the sign of the cross, indicating the end of the gospel and the beginning of the teaching.

Zain first makes mention of the upcoming season of the church, Lent. The story of Zacchaeus’s climb up the tree, he jokes, is “a nice way to say he was short,” bringing a light tone to a more introspective story. Zacchaeus, he said, “desired to see God” and went to great lengths to witness Jesus in the crowd.

Zain invites the congregation to meditate and imagine themselves in a crowd longing to see something or someone. “He desired to see Christ so much.” He is urging the congregation to consider their desire to see Christ in their own lives. “Everything we want to do in this life begins with desire.”

Zain has notes in his hands, but mostly speaks unaided. He wants to make sure the parishioners are inspecting their own hearts, and prompts them with a question: “What do we really love and desire more than anything else?” He references a meme about people in the cold watching a football game and compares it to the struggle of making it to church, whether it’s the cold or being unable to find parking. He pauses. This invites the listener to take stock of their spiritual habits.

“Zacchaeus is an example, brothers and sisters, for all of us,” he says. References to “we” and “us” let the parishioner know that Zain struggles himself, despite being a priest.

“Imagine that if God said I want to come and eat in your home,” the priest says. He engages the imagination using the gospel story. “We have to let Him in, and it begins with desire.” Zain refers to the idea of God living in people versus having worldly desires that push Him away. Worldly desires, he says, are “those things [that] fill our hearts and there’s no room for Christ.” He pauses again, providing a moment for the parishioner to examine their hearts. He moves onto this idea of cleansing oneself to make room for Christ, and that it begins with desire. He glances at his notes and references Revelation, “Behold I stand at the door and knock.” Christ is the one who knocks at the door in our hearts.

Zain’s voice grows louder to emphasize, “Today salvation has come to this house.” Zain wants his congregation to realize they can only respond to Christ when their desires are pure. Then we can hear His knocking on our hearts. He sends by saying, “Let us take this lesson with Zacchaeus and ask ourselves ‘what is our desire?’ That we may one day be worthy of the kingdom.” He ends with the sign of the cross, and the congregation does the same.

Day Four: Onto Derry, Where an Imperfect Peace Persists

LONDONDERRY - On Wednesday morning, we checked out of Gresham Hotel in Dublin, met our bus driver, Kevin, and began our trip to Derry. (Or is it Londonderry? More on that later.) Most students slept on the bus, curled up in their seats as the rain pattered down the windows. Others had a variety of conversations on journalism, the conflicts in Ireland and Israel-Palestine and Cadbury chocolate while we cruised through the hills of the Irish countryside.

Midway through the bus ride, Trisha Mukherjee broke out her white ukulele and played a variety of songs, accompanied by Professor Ari Goldman on the harmonica. Classmates sang along and took photos and videos of the spontaneous performance.

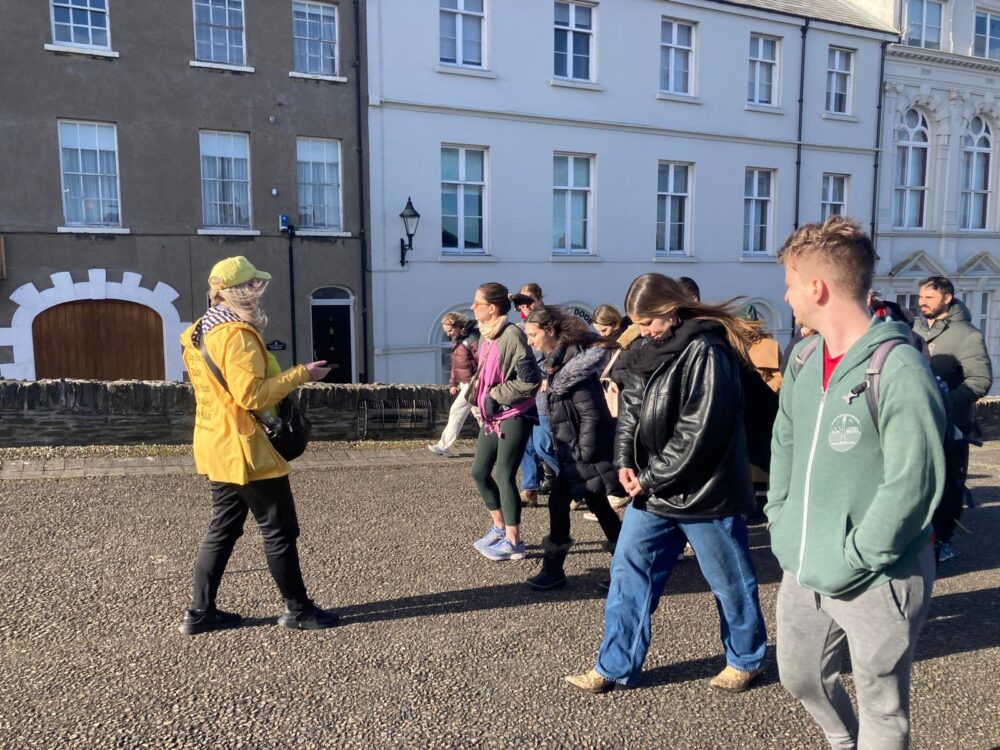

Around 2:20 p.m., we arrived at the Maldron Hotel in Derry and promptly embarked on a tour of the city led by Charlene McCrossan. Her late father, Martin, started Martin McCrossan City Tours during the Troubles. Charlene, who took over the business, is also the youngest tour guide in the United Kingdom to have received the Blue Badge, a prestigious certification for giving tours.

McCrossan led the tour around Derry, beginning with the River Foyle, which surrounds the city from almost all sides. She talked about the era of emigration from Ireland after the Great Famine. According to McCrossan, there are 75 million people in the world that claim Irish ancestry. “There’s an Irish pub in every capital in the world. Two or three if you’re lucky,” McCrossan said, echoing Ian Bermingham’s earlier point that celebrated the Irish people's diaspora culture.

She walked us through Derry’s founding from the 17th century, including the history of the building of the city’s infamous walls, making Derry the youngest fully intact walled city in the UK.

According to McCrossan, 72% of the current population of Derry is Catholic, and 28% is Protestant and other religious groups. But is it Derry or Londonderry? It’s clear even locals are undecided — with Catholic Irish nationalists mostly preferring the former and Protestant loyalists mostly the latter. Some signs show the “London” crudely scratched out (and on at least one sign, it had been written in again over the graffiti paint). Despite relative peace in the city for over 20 years, both loyalists and Irish nationalists still feel under attack in the city.

McCrossan peppered her tour with several references to the Netflix show Derry Girls. She spoke about the nostalgia it brought as she watched it and how it jogged her memory of the smaller details of her Protestant schooling as a Catholic during the 1990s. “More importantly, it’s educating our children as well,” she said. Later, the class even posed by a mural of the famous five protagonists!

McCrossan also broke down years of conflict between nationalist forces in Derry, showing us the cannons that remain in the walls from the siege of the city in 1689 and detailing the the Troubles, from the three-day riotous Battle of the Bogside in 1969 to Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British troops opened fire on unarmed protestors in the city, killing 13 at the scene.

Around 5, we got to tour the First Derry Presbyterian Church and hear more about the church's history from volunteer Joe Cuwan. He described the stained glass and how elaborate it is for a Presbyterian church. He then explained the reasoning behind why the burning bush is the symbol of Presbyterianism. There are hardships in life, but knowing that God is there gives comfort, Cuwan said.

We ended the day over a long, lingering dinner at the Walled City Brewery, in which Professor Greg Khalil proposed a “game” of answering questions about ourselves and our feelings about the trip thus far. It was enlightening and emotional to learn what our fellow classmates were experiencing. We walked back to the Maldron, noticing how the shape of the Peace Bridge over the river takes the form of a handshake: a wavy path to peace as imperfect and unpredictable as our journey through Ireland has been.

Edited by Samuel Eli Shepherd