Besties in Biblical Times

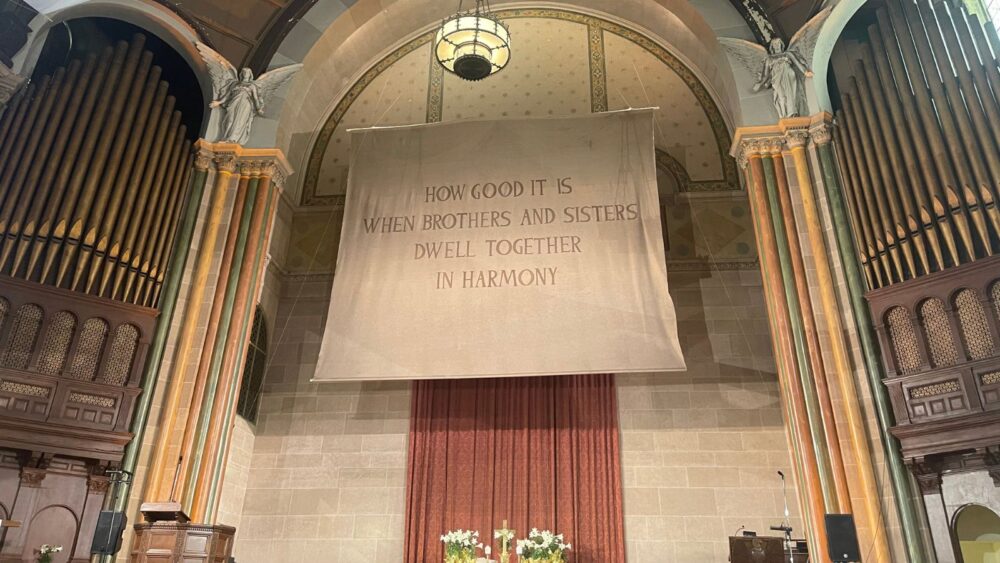

NEW YORK – Between two Christian spirituals, a rowdy group of seven kids run onto the stage during Sunday morning service at St. Paul & St. Andrew United Methodist Church on 86 Street on the Upper West Side.

A boy with a shaved head in a pink button-down takes the microphone and tells the congregation that he is going to his friend Jonah’s birthday party later that day. A coy girl in gingham with a long ponytail says her best friend Sophia always gives her presents. The congregation giggles.

However, the children’s chatty irreverence is not an interruption to the service. It’s time for the "Messages for All Ages" portion, during which the congregation’s youth and campus pastor, Ekama Eni, leads the children in a lesson before they head to the chapel for Sunday school. She teaches by example.

“I want to tell you about someone,” Eni says, leading off the message from the stage. She shows the children a photo of her friend Sam. “We cook together, we study together, we go to drag shows together. Would anyone like to tell me about their best friend?” What follows keeps the adults engaged, while the kids appreciate Eni saving them from the boredom of sitting quietly in a pew.

Eni tells the children that the Gospel reading they will hear while walking to Sunday school is about a man who is not feeling well and his four “besties.” The "besties" have heard that Jesus makes people better so they are going to take their friend to see him.

Theatrically retelling the story of Mark, chapter 2, when Jesus heals a paralyzed man, Eni says that the house where Jesus was at the time was very crowded, so the friends climbed onto the roof, cut a hole in the ceiling, and lowered their best friend into the house to see Jesus.

“That is dedication to being a bestie,” says Eni.

She emphasizes the importance of friends, those they can giggle with and do incredible things with, because Jesus loves them.

Eni, 30, graduated from Union Theological Seminary in 2021. She says that her approach to teaching kids is to invite mutual curiosity.

“I'm obsessed with the minds and thoughts of children,” she says after the service. “I'm always going to try and engage them most importantly as fellow human beings with thoughts and feelings.”

For Eni, it’s about making children feel like a part of the larger church community.

“Dear God, thank you for besties,” Eni says as she notices the children starting to get antsy. “Amen.” And the children scramble off to the chapel.