Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

As published in Columbia Journalism

Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

This year, Passover is stripped to its essence.

This has always been my favorite holiday: a weeklong religious ritual with grand, universal themes anchored by a Seder meal that encourages song, schmoozing, discussion, debate, and inter-generational sharing.

Passover is spring and renewal. It is brisket and matzo ball soup. It is, if you keep a kosher home and host two big Seders, as I traditionally have, utterly exhausting and absolutely worth it.

But this year, the very commandment to gather has been erased. Our family once held Seders with 25 people in our spacious, suburban dining room, arranging four tables to fashion a huge circle, unwieldy and glorious. Even in a New York City apartment, we managed to cram 18 people around a long, extended table, friends and family and the occasional stranger, all taking the journey together late into the night.

Not this year. This year, it’s just me and my husband, hoping to connect with children, siblings and friends across spotty Internet lines.

A family member is living in our city apartment and we are in our upstate home without all our usual Passover paraphernalia, and I miss it terribly. The English cutlery I inherited from my parents and only use this special week will stay in its locked cabinet. The elegant Elijah’s cup my late father gave me on the shelf. I won’t bring out the plague puppets and noisy toy frogs I’ve collected over the years for children’s entertainment, nor the colorful matzo covers the kids made in day school.

These precious objects represent the holiday, but they are not its essence.

I used to spend hours setting the table. It will take a mere moment when we sit down on Wednesday night, just the two of us.

And so what? I cannot lament the loss of things when all around us people are losing lives and loved ones. We still have the Seder. We still have the story.

The questions raised by the Exodus story, recounted in the Haggadah, take on added urgency and relevance in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. What does it mean to be free when we are confined? How do we maintain our identity and our communal associations in isolation? How do we nourish hope when we may well face the modern-day equivalent of wandering the desert for forty more years?

The Haggadah is infused with gratitude to God for enabling an oppressed people to break free. Many of us are grateful simply to breathe each morning. What are we learning about ourselves? How will we make our society healthier, kinder and more just when this is finally over?

I’ve never experienced a Passover of such hardship, but the Jewish people have endured worse, and there’s comfort in knowing that.

I fervently hope we will gather next spring, that I will fuss about the price of brisket and the state of my matzo balls, that I will spend hours setting the cutlery and decorating the table with all the items I’ve collected, that we will study the text and dream of drawing new meanings from it.

It won’t be the same, because we won’t be the same. Once we have had to focus on the essence of the holiday, we will know that what matters most is the story we recite year after year, together.

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

As published in Columbia Journalism

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

It is known as the “bread of affliction” for good reason. Matzo, the unleavened flatbread that Jews eat during the week of Passover in place of bread and other leavened food, is intended to remind us of hardship and flight. The ancient Israelites baked this bread quickly, before it had time to rise, as they hastily prepared to leave Egypt for their long march to freedom.

With a texture like corrugated cardboard and a taste to match, matzo is the bane of anyone trying to keep a home clean during this holiday. It crumbles as easily as Donald Trump’s ego, and leaves such an unappetizing mess that even our dogs wouldn’t touch it when it sprinkled on the floor.

Around this time in the holiday cycle — day five, or so — I would usually tire of eating this mandated mouthful. Really, how many times could I melt cheese on a matzo sheet and pretend I was eating a gourmet sandwich?

But the experience of this Passover has turned my hardened heart into a grateful one. Matzo, I now realize, is the perfect pandemic pantry item.

It lasts, well, forever. (I never understood the notion of “fresh matzo.” How could it taste less stale?)

It can be combined with other stay-at-home staples — eggs for matzo brei, peanut butter for something sticky, jam for something sweet, melted chocolate for something really sweet. In the morning, I break it up in tiny pieces, dry roast it on the stove, add raisins and nuts, and voila — an ersatz granola that will never see its expiration date.

The bread of affliction has become the manna of rescue. I used to scoff at my husband when, during the year, he kept an extra box of matzo to use in an emergency. No more. #WhenThisIsOver, I will appreciate that crumbly cracker anew. And I’ll think twice before ever buying bread again.

Jacuzzi Baptisms

Jacuzzi Baptisms

Kate Cammell | kac2261@columbia.edu

With the whirlpool setting off, the pastor enters a hot tub set up in the center of the church stage. One-by-one members, dressed in cotton tee shirts and athletic shorts, enter the tub for their baptism. Music swells from the praise band as the pastor guides each person through the process of dipping under water. With each dunk, the congregation erupts in applause.

This is the playbook of the monthly baptism services I grew up attending at Ada Bible, a nondenominational megachurch in Grand Rapids, Mich. Home to over 8,000 congregants, the church has four campuses scattered throughout the 200,000-person city. Each has been shuttered indefinitely as COVID-19 spreads across the nation.

These baptism services, slightly camp but moving, were always my favorites to attend. Kyle Pierpont, the Campus Pastor of the church’s Cascade Campus, often conducts the rite. He affirmed my sentiment as we talked the other day by phone saying, “yeah, people love them.”

Pierpont is a tattooed fourth-generation pastor with a grown-out brown beard and hair pulled into a bun that gives him an uncanny likeness to the Western iconography of Jesus. He’s in charge of pastoral care for the church and noted that it’s been difficult to uplift the community during this pandemic. Congregants are losing their jobs, loved ones are dying in isolation and everyone seems scared.

When Ada Bible closed its doors and went fully virtual on March 13, church leaders were hoping to reopen by Easter. Since then, the State of Michigan has enacted an executive order directing residents to stay at home through April 13, the state’s public schools are closed for the remainder of the academic year and the federal government has extended their social distancing recommendations through April 30. As of my writing this on Thursday April 2, cases in the state have risen past 9,000 and President Donald Trump is in the midst of public spat with Michigan’s governor, Gretchen Whitmer, that’s delaying medical aid to the region.

Returning to normalcy anytime soon is looking increasingly unlikely.

Ada Bible leadership is attuned to this. They’re preparing for a virtual Easter service. The church has been offering online sermons for over a decade, so adjusting to the technology and the congregation’s embrace of virtual pastoring were no problem. But still, there’s a void.

Pierpont said that he didn’t realize how much community took place in the liminal spaces of the physical building. Suddenly gone are things like saying hellos in the hallways, grabbing coffee in the atrium or striking up a conversation with the person who passes you the Half and Half. Gone also are the people who sit side-by-side as they cheer on those submerging in water on stage.

Those moments are now on hold indefinitely.

Pierpont has been thinking more lately about the meaning of baptism. Water washing away worldly sin, the act reminding those who partake that God invites them to an afterlife in heaven. On Easter he’s hoping to baptize people over Zoom. The recorded rite would then be featured during the church’s service. He thinks it’s a small way to remind people of the hope God offers even in difficult times.

While sitting at his kitchen table in front of the banana plant his wife got from Costco, Pierpont hopes to recite a blessing over Zoom as congregants dunk themselves in a body of water at their home, preferably a hot tub. Bathtubs could work too, though he confessed, “I don’t know I feel a little weird about the bathtub thing.”

Though I’m not particularly religious anymore, there’s something comforting during this time about returning to the church where I grew up, now by live stream in my East Harlem apartment. I’m stuck between needing to find meaning in this moment and wondering if I can. But I’m discovering, perhaps in an effort to etch some semblance of normalcy, moments of peace in reconnecting with a familiar community from afar.

One that I’d lost touch with until this pandemic.

Returning to church, I’m remembering that feeling of communion I had sitting at those hot tub baptisms of my youth. Cheering in chaotic unison for people as they cry and stumble off-stage smiling produces a connection that’s difficult to describe.

It’s easy for me to imagine the absurdity of it all to an outside eye—God being present in a hot tub on the pulpit of a warehouse-style church nestled in Midwestern woods. Now maybe even a clawfoot bathtub at someone’s home.

But in these moments of baptism, my church celebrates the idea that the people around us might find release and respite from the mortal world, a place where disease is real and no water can easily wash it away. As we watch the baptisms this Easter, there’s newfound hope that we might feel ourselves uplifted, too.

And, perhaps some congregants, like me, will find a much needed and special kind of levity that only comes from thinking about Jesus administering divine rescue via a Jacuzzi.

“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs”

“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs”

Meenketan Jha | mj2930@columbia.edu

It wasn’t meant to be like this, Swami Satyanand says.

In fact, since he became the head priest of a Hindu temple in Flushing, Queens 10 years ago, the festival of Chaitra Navaratri was always celebrated with dozens of devotees eating, drinking, praying and singing together. The children would clap along, he remembered, competing with one another to see who could make the loudest noise.

But this year, the festival, which celebrates the Goddess Durga and started on March 25th, was greeted with the soft chants of a handful of priests sitting a safe distance away from one another in the desolate confines of the temple.

Unimaginable, the swami says. With a majority of the world under quarantine and under self-isolation after the outbreak of Covid-19, community locations like mandirs have become ghost towns. Even the Hindu Gods have been forced to bend their backs to this modern-day pandemic. While Christian churches have managed to adapt to this unforeseen series of events by bringing the communion to the homes of the worshippers through technology, small-scale Hindu temples find themselves struggling to cope.

“There hasn’t been one soul permitted within temple compounds in the last two weeks,” says the Swami, who heads the Geeta Mandir at 92-11 Corona Avenue in Flushing. “It’s only been me,” he adds with a little sigh as he ends. Police have been surveilling the mandir from time-to-time, checking to see if it has remained closed. In the times of constant vigilance, these places of worship risk losing its core value of community.

Hindu temples in the United States have become like a weekend destination where parents take their children to for educational activities like shloka and traditional dance or singing classes. In a way, visiting a temple has been bred into the Indian-American lifestyle as a way of life. For young, new generation Indian-Americans, temples are like a telescope providing a glimpse into their heritage and ancestry.

The eeriness within the mandir halls has grown with passing time as self-isolation and quarantining become ever more paramount. The elongated hours of silence, which were previously sporadic, have become a part of everyday routine. The evening aartis are conducted by a solitary priest without the band of devotees singing and clapping along, the energy and vibrancy drained with them.

“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs,” says Satyanand explaining the role of a devotee. “Without people, religion is only texts, stories are just words and fragments. There is no emotion and vigor.”

The onset of the pandemic has put the Geeta Mandir in a troublesome position. With the situation only expected to get worse with proposed plans of an indefinite lockdown in place, the temple is at the risk of using up all of its resources like bhog, the offerings made to the God, often brought by the devotees as a way of saying thanks. Usually, bhog is a mixture of richly curated range of diverse food items, but with the restrictions in place Swami Satyanand says that they are limited to presenting God with rice and dal, or lentil soup.

Despite the challenges that the temple faces, Swami Satyanand says that health and safety of the devotees remain an utmost priority. “Once this passes, we’ll all come back stronger and serve God with a truer devotion than we had been before,” he assures me.

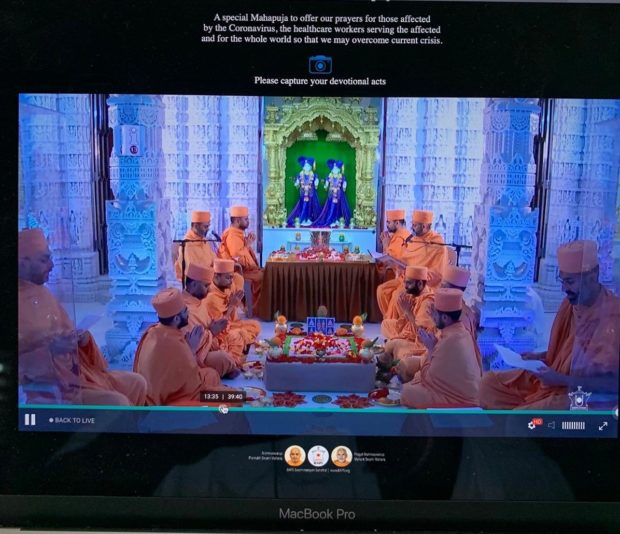

Hinduism in the United States has come a long way. The country is now home to more than 400 Hindu temples and not every temple has been tested like the Geeta Mandir. The BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, which has more than 3,800 centers across the world, has taken the aartis to its followers through technology. One of the most influential centers of Hinduism, BAPS provides spiritual nourishment to those who need their faith at this time virtually through venerations that are broadcasted live for other devotees to follow through their website.

“While we can’t recreate the human touch and the personal connections through these virtual sessions, we do try to reduce the physical distance,” says Kashyap Patel, a member of the BAPS community. The organization runs a weekly program for young children, teenagers, college students, and adults.

On this week’s agenda was the topic of positivity. High school students discussed together on how to remain optimistic as these unprecedented times pass us by. The students were asked to always look for the source of light, no matter how small, in the dark.

Community Never Dies, it Just Evolves

Community Never Dies, it Just Evolves

Esohe Osabuohien | eco2132@columbia.edu

Attending church online was not a new concept for me. Many of the mega churches back home would conduct online services with the option to stream via their websites or Facebook. Even my church home, Russell Street Missionary Baptist, a relatively small Detroit based church with a congregation of about 50 adults over the age of 65 and their grandchildren, would stream service through Facebook live for members to tune into from the comfort of their homes.

However, what was new to me was the need to tune into service frequently.

Before moving to New York, I might have watched our streaming services once or twice; video lag would often keep me from enjoying the Word. Nevertheless, I would always connect to my faith in some other shape or form be it: reading my Daily Devotional on the Bible app, listening to religious and spiritual podcasts, reading a religious WhatsApp message from Nigerian Aunties, or just listening to gospel music. But, since moving to New York City and starting grad school, I must admit that I had fallen off with keeping my faith.

In the last nine months I had gone to church four times, once in September 2019 when I was trying to find a new church home in New York City, once in January 2020 when I went back home to Detroit, and twice in February for reporting assignments. My Bible app and WhatsApp messages went unopened, taking my 362-day reading streak in the Bible app back down to day one. I rarely felt inclined to tune into church service be it through my church’s Facebook live, listening to Bishop T.D. Jakes’ podcast, or attending the virtual service of another popular Detroit based church.

I felt as though God knew my heart. I was still a member of the flock, following and trying to lead by example, but I was also busy.

However, this all changed in March. As the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) started sweeping through the nation, I felt the need to reconnect.

On Sunday March 15, I attempted to tune into my church’s Facebook livestream, the lag bothered me so I tried a different service and called my mom to see if she was tuned in as well. She was. She was also trying to help my 91-year old grandmother who lives alone and does not have a smartphone, but knows all about what’s trending on Facebook and social media listen in. Despite some technical difficulties, we were connected. On Tuesday of that same week, I tuned into an Instagram live tarot reading hosted by TatiannaTarot, a New Orleans based Diviner, spiritualist and Iyanifa – a priestess of the Yoruba tradition. I wanted to see if she had any messages for the week, or anyone I could connect to for follow-up on my story about followers of the Yoruba tradition. During her four-hour or more session, there were at least 500 people tuned in and asking questions or seeking guidance from either her or their ancestors, she responded and gave a reading for almost every question.

Both the Sunday service with my family, and her reading gave me something that I had been missing for a while, spiritual restoration and a globalized sense of community.