Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

As published in Columbia Journalism

Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

This year, Passover is stripped to its essence.

This has always been my favorite holiday: a weeklong religious ritual with grand, universal themes anchored by a Seder meal that encourages song, schmoozing, discussion, debate, and inter-generational sharing.

Passover is spring and renewal. It is brisket and matzo ball soup. It is, if you keep a kosher home and host two big Seders, as I traditionally have, utterly exhausting and absolutely worth it.

But this year, the very commandment to gather has been erased. Our family once held Seders with 25 people in our spacious, suburban dining room, arranging four tables to fashion a huge circle, unwieldy and glorious. Even in a New York City apartment, we managed to cram 18 people around a long, extended table, friends and family and the occasional stranger, all taking the journey together late into the night.

Not this year. This year, it’s just me and my husband, hoping to connect with children, siblings and friends across spotty Internet lines.

A family member is living in our city apartment and we are in our upstate home without all our usual Passover paraphernalia, and I miss it terribly. The English cutlery I inherited from my parents and only use this special week will stay in its locked cabinet. The elegant Elijah’s cup my late father gave me on the shelf. I won’t bring out the plague puppets and noisy toy frogs I’ve collected over the years for children’s entertainment, nor the colorful matzo covers the kids made in day school.

These precious objects represent the holiday, but they are not its essence.

I used to spend hours setting the table. It will take a mere moment when we sit down on Wednesday night, just the two of us.

And so what? I cannot lament the loss of things when all around us people are losing lives and loved ones. We still have the Seder. We still have the story.

The questions raised by the Exodus story, recounted in the Haggadah, take on added urgency and relevance in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. What does it mean to be free when we are confined? How do we maintain our identity and our communal associations in isolation? How do we nourish hope when we may well face the modern-day equivalent of wandering the desert for forty more years?

The Haggadah is infused with gratitude to God for enabling an oppressed people to break free. Many of us are grateful simply to breathe each morning. What are we learning about ourselves? How will we make our society healthier, kinder and more just when this is finally over?

I’ve never experienced a Passover of such hardship, but the Jewish people have endured worse, and there’s comfort in knowing that.

I fervently hope we will gather next spring, that I will fuss about the price of brisket and the state of my matzo balls, that I will spend hours setting the cutlery and decorating the table with all the items I’ve collected, that we will study the text and dream of drawing new meanings from it.

It won’t be the same, because we won’t be the same. Once we have had to focus on the essence of the holiday, we will know that what matters most is the story we recite year after year, together.

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

As published in Columbia Journalism

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

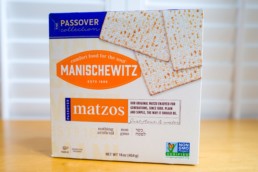

It is known as the “bread of affliction” for good reason. Matzo, the unleavened flatbread that Jews eat during the week of Passover in place of bread and other leavened food, is intended to remind us of hardship and flight. The ancient Israelites baked this bread quickly, before it had time to rise, as they hastily prepared to leave Egypt for their long march to freedom.

With a texture like corrugated cardboard and a taste to match, matzo is the bane of anyone trying to keep a home clean during this holiday. It crumbles as easily as Donald Trump’s ego, and leaves such an unappetizing mess that even our dogs wouldn’t touch it when it sprinkled on the floor.

Around this time in the holiday cycle — day five, or so — I would usually tire of eating this mandated mouthful. Really, how many times could I melt cheese on a matzo sheet and pretend I was eating a gourmet sandwich?

But the experience of this Passover has turned my hardened heart into a grateful one. Matzo, I now realize, is the perfect pandemic pantry item.

It lasts, well, forever. (I never understood the notion of “fresh matzo.” How could it taste less stale?)

It can be combined with other stay-at-home staples — eggs for matzo brei, peanut butter for something sticky, jam for something sweet, melted chocolate for something really sweet. In the morning, I break it up in tiny pieces, dry roast it on the stove, add raisins and nuts, and voila — an ersatz granola that will never see its expiration date.

The bread of affliction has become the manna of rescue. I used to scoff at my husband when, during the year, he kept an extra box of matzo to use in an emergency. No more. #WhenThisIsOver, I will appreciate that crumbly cracker anew. And I’ll think twice before ever buying bread again.