“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs”

“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs”

Meenketan Jha | mj2930@columbia.edu

It wasn’t meant to be like this, Swami Satyanand says.

In fact, since he became the head priest of a Hindu temple in Flushing, Queens 10 years ago, the festival of Chaitra Navaratri was always celebrated with dozens of devotees eating, drinking, praying and singing together. The children would clap along, he remembered, competing with one another to see who could make the loudest noise.

But this year, the festival, which celebrates the Goddess Durga and started on March 25th, was greeted with the soft chants of a handful of priests sitting a safe distance away from one another in the desolate confines of the temple.

Unimaginable, the swami says. With a majority of the world under quarantine and under self-isolation after the outbreak of Covid-19, community locations like mandirs have become ghost towns. Even the Hindu Gods have been forced to bend their backs to this modern-day pandemic. While Christian churches have managed to adapt to this unforeseen series of events by bringing the communion to the homes of the worshippers through technology, small-scale Hindu temples find themselves struggling to cope.

“There hasn’t been one soul permitted within temple compounds in the last two weeks,” says the Swami, who heads the Geeta Mandir at 92-11 Corona Avenue in Flushing. “It’s only been me,” he adds with a little sigh as he ends. Police have been surveilling the mandir from time-to-time, checking to see if it has remained closed. In the times of constant vigilance, these places of worship risk losing its core value of community.

Hindu temples in the United States have become like a weekend destination where parents take their children to for educational activities like shloka and traditional dance or singing classes. In a way, visiting a temple has been bred into the Indian-American lifestyle as a way of life. For young, new generation Indian-Americans, temples are like a telescope providing a glimpse into their heritage and ancestry.

The eeriness within the mandir halls has grown with passing time as self-isolation and quarantining become ever more paramount. The elongated hours of silence, which were previously sporadic, have become a part of everyday routine. The evening aartis are conducted by a solitary priest without the band of devotees singing and clapping along, the energy and vibrancy drained with them.

“It’s like faith has lost one of its legs,” says Satyanand explaining the role of a devotee. “Without people, religion is only texts, stories are just words and fragments. There is no emotion and vigor.”

The onset of the pandemic has put the Geeta Mandir in a troublesome position. With the situation only expected to get worse with proposed plans of an indefinite lockdown in place, the temple is at the risk of using up all of its resources like bhog, the offerings made to the God, often brought by the devotees as a way of saying thanks. Usually, bhog is a mixture of richly curated range of diverse food items, but with the restrictions in place Swami Satyanand says that they are limited to presenting God with rice and dal, or lentil soup.

Despite the challenges that the temple faces, Swami Satyanand says that health and safety of the devotees remain an utmost priority. “Once this passes, we’ll all come back stronger and serve God with a truer devotion than we had been before,” he assures me.

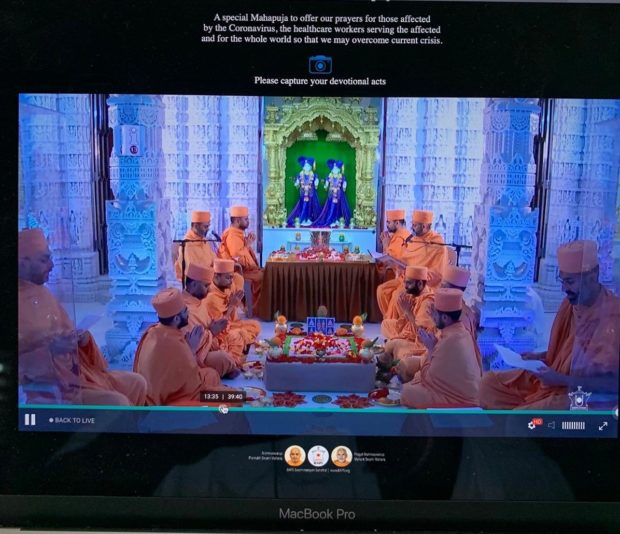

Hinduism in the United States has come a long way. The country is now home to more than 400 Hindu temples and not every temple has been tested like the Geeta Mandir. The BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, which has more than 3,800 centers across the world, has taken the aartis to its followers through technology. One of the most influential centers of Hinduism, BAPS provides spiritual nourishment to those who need their faith at this time virtually through venerations that are broadcasted live for other devotees to follow through their website.

“While we can’t recreate the human touch and the personal connections through these virtual sessions, we do try to reduce the physical distance,” says Kashyap Patel, a member of the BAPS community. The organization runs a weekly program for young children, teenagers, college students, and adults.

On this week’s agenda was the topic of positivity. High school students discussed together on how to remain optimistic as these unprecedented times pass us by. The students were asked to always look for the source of light, no matter how small, in the dark.

A Symbol of Sikh Identity

A Symbol of Sikh Identity

Meenketan Jha | mj2930@columbia.edu

I stood there stranded, clueless as to where to go. On either side of me, a crowd of men and women rushed past to take their place. I was visiting a Sikh temple in Queens, a house of worship as a Gurudwara. Right in front of me was the Guru Granth Sahib, the central religious scripture in Sikhism. I peered around to pick the best location to sit. Hair uncovered I was sticking out like a blue bowl sitting in a cupboard full red dinnerware. Aside from my phone buzzing at maximum volume, the space was filled only with the subtle noise of the hymns of kirtan.

Men and women sat separately on either side of the room; even the young children were separated by gender. While the gender split is a common part of religions originating from the Asian subcontinent, a lot of such unsaid rules are rarely a part of modern-day practices. Although this isn’t an obligation, Sikhism is one of the few faiths where original gurus teach on equality between the sexes giving women equal rights in all spheres of the belief. One can view the segregation as a sign of balance between the two sexes – not one needing to be dependent on the other.

All those gathered at the Temple, on Broadway and 61st in Flushing, Queens, regardless of gender, had covered their hair. Men wore the Sikh turban and women used their shawls to cover their hair. The turban has always been an essential part of daily attire for a Sikh male. The head of the Gurudwara, Brahm Das ji, wore the look of horror as he scurried towards me.

“Cover your hair, son!” he said as he pulled me to the outside of the hall handing me over a handkerchief with a picture of the khanda, a symbol of Sikhism, adorned on it. “Have you never been to a Gurudwara before?”

Although I lived most of my life in India, I had never been to a Gurudwara before. In a Hindu temple, which I frequent, men do not have to cover their heads though the same rule doesn’t apply for women.

I scampered to cover my hair. Those who did not have a turban took handkerchiefs from around their heads, before giving me an odd look as I struggled with mine. Seeing my fruitless attempt, Amitoj Singh, a man in his early 30s came to help me.

“Your first-time son?” he asked. I nodded asking him why it was imperative that I cover my hair. “It’s maryada (modesty),” he replies. “An act of benevolence towards the Higher Being who dictates my life and makes miracle happen every day, I am bowing to the almighty in thanks and gratitude.”

One of the world’s newer religions, Sikhism derives its principles from faiths all over while adding a few uncompromising components like cleanliness. Unlike other religions, Sikhism’s core values call for cleanliness, respect, valor, perseverance, and equality. The turban houses and protects uncut hair, a sacred custom for those who follow the faith, the hair is tied up to the important spiritual center of your body – the Dasam Duar (7th Chakra). Crossing the pressure points on our temples, the turban helps an individual keep calm and reserved in times of turmoil and prayer.

“Nowhere in the Guru Granth Sahib does it say you have to wear a turban, but we do it. Why? Because the turban is a symbol of pride, valor, and distinction (naira), the last of the Sikh gurus is said to have his blessings on all those who stay naira,” says Brahm Das Ji in a conversation with me once the ceremony is over.

Brahm Das adds that because the turban makes Sikhs stand out, it also makes them accountable for their actions. The faith says that everybody is equal in God’s eyes and sex does not hinder your relationship with God. It also disregards, in theory at least, Hinduism’s rigid, structural caste system where people are subjected to a position on four-tier based social strata.