Meeting the Shabbat Bride

As the sun set on Friday evening, the congregation at Stephen Wise Free Synagogue sat at least six feet apart from each other, indicating a sign of the pandemic that’s engulfed the world for the past two years. The service began with six songs led by Cantor Daniel Singer, from the Kabbalat Shabbat, one to symbolize each day of the preceding week leading up to this service.

As the songs continued, everyone in attendance remained standing, facing the front of the Synagogue, where the Torah rests and the Cantor stands. Some participants clap to the beat of the song. Others gently rock back and forth. Some do a combination of both. Each song flows from one into another, with no break. The melodies merge from one to the next, with Cantor Singer saying which page to turn to in between the first verse of the songs.

On the seventh song, the service changes unexpectedly and without warning.

With no prompting from the cantor, everyone silently turns towards the back of the synagogue before they start singing, with no prompting from the Cantor. They all know what to do. Next steps and movements are all ingrained, as they slowly turn around while singing. The flow of the service up until this point could be analogized with the beginning of a traditional Western wedding. There is a prelude of songs, where everyone faces the front, and then when it is time for the bride to make her grand entrance, the crowd faces her. Each person smiles as they sing the seventh song, welcoming the long-awaited day of rest as if it were a young woman walking down the aisle.

Instead of focusing on the memorial plaques on the rear wall, all eyes are on the main door of the synagogue. For the remainder of the song, the door is the main focus. The clapping and rhythmic movement ceases, as they usher in the true beginning of Shabbat.

A small red light turns on next to some names on the memorial back wall. The lights symbolize an anniversary of death. But, death is not the focus in this ritual. Instead, the focus is the ultimate symbol of love and life, marriage.

In this case, the bride is the Shabbos everyone is welcoming. The lyrics of the song translate in English to, “Beloved, come to meet the bride; beloved come to great Shabbat.”

Singer explained that this tradition comes from the Jewish Mystical tradition, the Kabbalah. Welcoming Shabbat as a bride, he said, “is a metaphor for the time of redemption.” The Hebrew, “Boi Kallah,” means “come my beloved.” One day, the goal is to reach a day when the Messiah will come, and everyone will be peace.

“We pray for a day when we’ll be able to have Shabbat rest all the time,” Singer said.

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Kathleen Shriver

Some of the best views of New York’s Statue of Liberty are from a waterside park in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood. From there, visitors can see the broken shackles at Lady Liberty’s feet, the golden fire raging from her copper torch, and the words to “The New Colossus,” the sonnet at her pedestal.

Just a few blocks from New York’s Statue of Liberty, a nonprofit restaurant and school labors to keep the spirit of Lady Liberty alive. It is known as Emma’s Torch, a tribute to Emma Lazarus, the Jewish American poet whose verse -- “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe” – decorates Liberty’s pedestal. Founded by Kerry Brodie, Emma’s Torch aims to empower refugees, asylum seekers, and survivors of human trafficking through culinary education.

When launching the nonprofit, 27 year old Brodie, thought back to her highschool -- Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School -- where she learned about Jewish leaders. She says Lazarus was one of the “unsung female heroes of Jewish history” whose work always stuck with her.

“I felt like Emma never got to see what her poem would become,” Brodie said. “ So my hope is that Emma's Torch will also be able to create that sort of lasting legacy and those ripple effects of change as well.”

In the Jewish tradition, when speaking of a righteous deceased person, many will say Z"l (pronounced zal), which is an abbreviation for Zikronam L'bracha. This literally means “may their memory be for a blessing.” “I think this definitely applies to how we are trying to honor Emma's legacy and memory. We are working in her memory,” Brodie says.

While for many restaurants, reopening after the pandemic means staffing up, adding tables, expanding menus, opening the doors earlier and closing them later, for Brodie, it means reprioritizing. It means reconsidering the purpose of Emma’s Torch and drawing from her past and, as it turns out, her faith.

Since its founding in 2017, Emma’s Torch has become a beacon of hope for hundreds. The nonprofit offers a full-time paid training program, during which students receive instruction, mentorship, and work experience, while also developing English conversation skills and other “soft skills” such as resume development and computer literacy.

In 2020, Brodie was looking forward to formalizing and publishing her curriculum and opening new locations around the country.

“2020 was supposed to be the year of stability,” she said. Instead, she got a global pandemic, an economic crisis, and a racial reckoning.

While the pandemic threatened the lives and livelihoods of everyone, the toll it took on those working in the restaurant industry was especially dire. To make matters even worse, Emma’s Torch doubled as a training program for immigrant communities, some of the country’s most vulnerable. Even so, Brodie had faith.

Brodie’s Jewish faith has gotten her family through a profoundly difficult past. “My great grandparents are among the only people from their families, to survive the Holocaust,” she said.

She recalled that several years ago she joined her grandfather on a trip to Lithuania, where many members of his family were murdered by the Nazis. “Standing there was just such an eye-opening experience of what happens when we don't remember that our neighbors are not that different to us, and that's just always stuck with me,” she said.

Ever since this experience, Brodie has been particularly motivated by the Jewish practice of welcoming the stranger. A commandment that is repeated 36 times in the Torah, the scripture reminds Jews that they once “were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 19:33-34). “We hope to live up to this commandment and imperative in our work.” At the same time, Brodie doesn’t see these values as exclusive to Judaism.

She loves learning from her students how these same values can come from different life experiences, including other religious traditions.

“At Emma’s Torch, a lot of times either our students come from very strong backgrounds of faith, or are supported and have found friends through their religious community, whether that be a church or a synagogue or mosque,” she said. “Faith in general can be such a powerful tool to bring people together.”

These universal values of unity and welcome have motivated every step of Brodie’s career. After graduating from Princeton University with a degree in Near and Middle Eastern Studies, Brodie hoped to effect change through public policy.

Following two years of policy work at the Israeli Embassy in Washington DC, she became the press secretary for the Human Rights Campaign, a nongovernmental agency based in Washington D.C., where she publicized the organization’s international work. At the same time, she spent her free time meeting with women who inspired her next endeavor.

“I started volunteering at a homeless shelter and was really struck by the conversations about food that I would have with the women at the shelter,” she said.

Brodie wanted to cook with the women. She grew up learning to cook different dishes that connected her to her family’s religious and cultural history and inspired her pride in that history. She wanted to find a way to use food to do more than just feed these women. She wanted food to empower them, too.

“Recipes are not simply a list of ingredients. Each is wrapped in memories,” she said. “Cooking simultaneously defines and transcends our communities.”

Growing up, Brodie would visit her grandparents in South Africa, where they had found refuge during World War II. Both of Brodie’s parents were raised in South Africa and her grandparents still live there today. And during her earliest visits to her grandparents, Brodie learned to cook.

“My grandmother makes the most incredible milchika which are basically South African cinnamon buns. One of my earliest cooking memories is helping her make these.” While many American Jews have foods like bagels-and-lox to break their fasts on the Jewish High Holidays, South African Jews break their fast with milchika–a kind of cinnamon bun. Dishes like milkchika and the religious traditions around sharing them with family and friends has always inspired Brodie to see food as a powerful element in strengthening her faith and in enforcing a shared sense of identity amongst her community of faith.

For this reason, she encourages her students to embrace and celebrate their origins and home countries when they cook.

“Food helps our students understand that they’re not victims and that their work is valuable,” she says. Brodie says that she wants her students to see that each of their unique understandings of flavor and culture can actually enhance our communities and inspire our kitchens.

Inspired by her love of food and her conversations with the women at the homeless shelter, Brodie started reading about the restaurant industry. She read about widening labor gaps and about restaurants struggling to find talent to build out their kitchens.In May of 2016, Brodie left the HRC and began studying at the Institute of Culinary Education.

When she wasn’t learning to cook, Brodie was working to build out the organization of her dreams: a restaurant that would provide opportunities for the most vulnerable, a restaurant that would tell stories through its food.

She wanted to provide jobs for those who were left out. She wanted to bring people of different backgrounds and life experiences together in a space that felt comfortable to all of them; in a space where they could connect and realize that they could, in fact, work together. That space was the kitchen. And after graduating from culinary school in June of 2017, Brodie launched her first pilot program at Emma’s Torch.

Emma’s Torch began offering a free 12-week apprenticeship program with up to 500 hours of culinary and professional training. What’s more, students were paid to participate, allowing them to train full-time and cover expenses.

By the end of 2019, over 100 students had graduated from the program with professional culinary skills, English proficiency, and a community of support. Ninety-seven percent of the graduates had been placed in culinary jobs around the city.

And then, the pandemic hit. Like most people working in the hospitality industry in New York, many alumni were laid off or furloughed and Brodie was forced to close her training program and restaurant. She closed the doors of her restaurant and sent her students and staff home. But Brodie didn’t give up.

She turned her faith into action. The organization remained stable due to support from donors and a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Meanwhile, the Emma’s Torch staff began volunteering to work with students and alumni online. They hosted online cooking classes while also helping students and alumni apply for unemployment benefits. And Brodie innovated, working with old and new partners on her “Culinary Council” to restructure the business in response to the shifting industry.

After six months of solely online programming, Emma’s Torch reopened in October of 2020 with a three track program including the original culinary program in addition to two new tracks for alumni: the first being a community building program and the second a management-level leadership development fellowship for select program graduates.

Ruslan Abdraimov, a graduate of Emma’s Torch, participated in the fellowship. Abdraimov arrived in New York from Russia in 2016 with just $216 in his pocket and no understanding of the English language. Fleeing cultural and political persecution, he left everyone and everything he knew behind – for a chance to start over in America.

He knew one person in New York, who loaned him his sofa and told him about Emma’s Torch. Abdrainmov applied to the pilot program in 2017 and became a student in the first graduating cohort at Emma’s Torch.

Abdraimov remembers making 12 dishes on his graduation night. “I can’t choose a favorite,” he laughs. “It’s like asking [me] to pick [a] favorite child.”

But four of the dishes made him especially proud – a combination he calls “Winter’s Heat.” The roasted buckwheat katah, celery potato mash, sauerkraut stir fried with German sausage, and deep fried mushroom stuffed meatballs use all the vegetables available during winters in Russia. “Winters in a large part of Russia are long and cold. And you have to eat a lot to keep yourself warm,” he says with a smile.

Abdraimov describes his experience at Emma’s Torch as more than just an education in the culinary arts.“You know, it’s one thing when you hear about different countries and religions, but the other thing is, when you actually have a chance to meet that person and spend some time in a kitchen with that person, you know, and be around them every day, like for eight to 10 hours a day,” he said, nodding his head. “You learn a lot. And behind all that history, it’s something universal -- things like kindness, friendship.”

As Brodie shifts her focus to the students and alumni, the flames of Lady Liberty’s fire continue to burn at Emma’s Torch, which has transformed into a take-out cafe. As it was before the pandemic, the menu remains “New American cuisine,” cooked by New Americans.

‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

As published in the Columbia News Service

‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

Lily Lopate

Kosher cooking has a lot of rules, but that doesn’t mean that learning kosher cooking isn’t fun. During a pastry workshop at the Kosher Culinary Center in Brooklyn in July, the students — six women, one teenage boy and one man — were tasting bite-sized cocoa pear muffins that had just emerged from the oven. “These muffins are perfect for a ladies’ brunch, bridal shower or bris,” said Avram Wiseman, 64, the Center’s co-founder and chef. As the class inspected the flecks of melted chocolate and grated pears, the teenage student looked despondently at a muffin that overflowed in the baking tray. Wiseman noticed. “What do we do with our mistakes?” he asked. “We eat them!”

There’s plenty of humor at the Kosher Culinary Center, especially since it reopened to full capacity cooking classes this summer. Located in Sheepshead Bay, between Marine Park and Mill Basin, the center offers recreational cooking classes, a catering business and a professional culinary training program.

Because people experience faith at varying degrees, the center’s aim is inclusivity, and its students make up an eclectic mix of Orthodox, Conservative and Reconstructionist Jews. “We cater to everyone regardless of how religious they are,” said the center’s director and co-founder, Perline Dayan, 53. “One does not need to have knowledge of kashrut laws prior to starting our program.”

This attempt to create common ground, through food, among segments of the Jewish population that may otherwise be isolated from each other has made the center a place for members of the Jewish Brooklyn community to connect or reconnect. Recreational and professional classes are open to men and women, ages 16 and older. And things are getting busy again now that in-person gatherings are less restricted than they were last summer. “Once people got vaccinated, our class size shot up,” said Dayan.

The increased number of students has inspired the school to apply for full accreditation, which would grant it an added degree of recognition as an educational institution. It’s currently the only trade school licensed by the state of New York to teach the skills needed to work in the kosher food industry.

In addition to its classes, the center’s also seen an increase of customers who book the venue for social events. People come for Jewish Singles Night or Culinary Date Night. “The date nights always fill up fast,” said Dayan. “A few couples meet for the first time and make a signature cocktail, kalamata olive focaccia and the chef’s choice of hors d’oeuvres.” The center has also resumed catering for large party events up to 50 people, a significant increase from the 10-person average last summer.

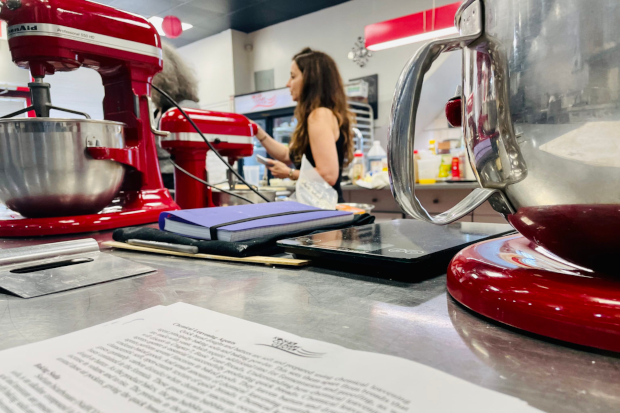

The center certainly has the look of a place where serious cooking happens. In the airy, industrial-sized teaching kitchen are red cupboards filled with baking tools, large pieces of cookware hang from a pot rack that wraps around the ceiling and students wearing black aprons work at long silver tables. A Star of David and printouts of Hebrew prayers are taped to the entryway wall. Opposite the sink, a framed plaque displays the kosher certification signed by two rabbis from the Northern American Kosher Supervision. If it weren’t for these hints of Judaism, the Kosher Culinary Center — which founders say is the only school outside of Israel to offer professional training in the kosher culinary arts — looks just like any professional cooking school.

Wiseman’s classes are the most popular, said Dayan. “Students love him,” she said. It is easy to see why: his sense of humor and playfulness in the kitchen allows him to quote apt lessons from the Torah as he’s teaching. In a class on “quick dry breads,” Wiseman asked, “What is the origin of unleavened bread?” And when students answered “Passover,” he explained further. “When Pharoah agreed to let the Israelites go, they hurried out of Egypt. They were in such a hurry they could not let their bread rise all the way so they took it with them just as it was starting to rise. So, there you go — quick bread.”

Wiseman teaches classes in both the professional and recreational tracks. Recreational classes are shorter and focus on one theme, like breads, desserts or meats. Professional classes are much more intensive. They include 216 hours (or 54 days) of hands-on training in technical professional skills and techniques. Courses last 11-16 weeks, and participants must enter with a high school diploma or equivalent degree to obtain a certificate from the culinary program. Students are drilled on how to cook safely and skillfully in a kosher environment, and the course’s difficulty escalates from knife skills to breads, starches, stocks, fish and meat.

The school also provides counseling, networking opportunities and interview preps to help students make the transition into a full-time culinary job. Come the end of the term, students in the professional classes must take a final exam to test their knowledge of kosher rules.

Before co-founding the center with Dayan in 2015, Wiseman had been teaching for several years, most recently at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts in Brooklyn, which closed in November 2015. He had also worked in a variety of settings, including the United Nations, where he was the executive sous chef. In that role, he said, “I cooked for several presidents: Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon. Each one had their quirky favorites.” He also cooked there for Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen.

Though he keeps kosher, Wiseman’s years in the culinary industry were spent cooking in non-kosher kitchens at a large, restaurant scale. His vast career network allows him to connect students with colleagues in the industry. “I’m doing this so people can gain a parnassah [the tools to make a decent living],” Wiseman said. It’s a way of passing on the trade through generations.

Dayan met Wiseman when she took a class of his in 2013 at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts. “It opened up a whole new world. I had never tasted a beet before,” she said. Dayan, like many of Wiseman’s students, is a career switcher. After years working in the trading firm Ladenburg Thalmann and Co., she wanted a change.When the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts was forced to close because it was operating without a license, Wiseman and Dayan decided to form a partnership. “I come from accounting and he’s a professional chef,” she said. “We decided to start our own school.”

Their vision was to create a modern twist on kosher cooking. “We do traditional Jewish foods, but we do them with style,” said Wiseman. “It’s not your mother’s potato latkes. We make it gourmet.” To stay relevant, they also teach a range of global cuisines including French, Italian, Vietnamese and Greek. Recently, at the request of one student, Sephardic dishes were added such as cassola (sweet cheese pancakes), buñuelos (puffed fritters with an orange glaze), keftes de espinaka (spinach patties), and keftes de prasa (leek patties).

For Dayan, an observant Jew, the kosher component was critical to the partnership. “If it wasn’t going to be a kosher school then I wouldn’t be here,” she said. To be fully compliant as “kashrut” (kosher), the kitchen must be supervised by a rabbi, and a certified “mashgiach” (the kitchen supervisor), must always be present. The kashrut rules are strict and unyielding: no meat can coexist with dairy in the kitchen and even meat and dairy utensils must be separated. Recently, a younger student entered class with a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and, when asked whether it contained milk, was directed to go outside and immediately throw it away. It is common practice to toss out or “tear” food that is out of order. (The Yiddish word “treif” derives from the Hebrew word for torn).

Across the spectrum of Judaism, the level of piety in the kitchen may vary. A nostalgic relationship to Jewish cuisine is sometimes described derisively as “Kitchen Judaism,” referring to Jews for whom religion revolves mainly around food. At the center, the connection between faith and food is clearer. “There’s more to Judaism than just being Jewish and cooking at the same time,” said Dayan. “So, if we have someone who is new to Judaism, we educate them on aspects of the religion.”

But regardless of the degree of piety, once students come to the center, they are part of the “whole mishpachah” (family) as Leah Waronker, a recent high school graduate and volunteer at the center, described it. “To cook kosher is to have faith in Judaism,” she said. “There’s a real intimacy that comes from working inside this community. From the moment I first put on my apron, I was welcomed with warmth. I literally fell in love.”

Back in the kitchen classroom, the smell of baked apple and cinnamon fills the room as the students begin preparing country-style biscuits. “Gentlemen,” Wiseman said to the two males in the class, “when you’re working with the flaky dough, bring out your feminine side. Be tender.” If the dough lacks moistness, he recommended more kosher butter (a non-dairy substance akin to margarine). “We grab the block of frozen butter, and we grate it like mozzarella cheese into the bowl. Now, we add vanilla. Say it with me,” he said, waving a wooden spoon like a conductor. The class recited the words after him “van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a.”

For Alla Dorch, an architect and student in the pastry class, baking kosher started as a peripheral activity and is now central to her life. “Cooking is usually something I do on the way to doing something else, you know?” she said. “I have my own design studio, so this started as something I could do with my family. But now I realize the crossover with architecture and pastry — both are very precise.” As Dorch’s interest in kosher culinary arts has grown, she is now considering starting a baking business. “It’s funny,” she said. “I used to go to synagogue to think about what comes next in my life. Now I come here.”

Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

As published in Columbia Journalism

Dispatch from a Pandemic Passover

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

This year, Passover is stripped to its essence.

This has always been my favorite holiday: a weeklong religious ritual with grand, universal themes anchored by a Seder meal that encourages song, schmoozing, discussion, debate, and inter-generational sharing.

Passover is spring and renewal. It is brisket and matzo ball soup. It is, if you keep a kosher home and host two big Seders, as I traditionally have, utterly exhausting and absolutely worth it.

But this year, the very commandment to gather has been erased. Our family once held Seders with 25 people in our spacious, suburban dining room, arranging four tables to fashion a huge circle, unwieldy and glorious. Even in a New York City apartment, we managed to cram 18 people around a long, extended table, friends and family and the occasional stranger, all taking the journey together late into the night.

Not this year. This year, it’s just me and my husband, hoping to connect with children, siblings and friends across spotty Internet lines.

A family member is living in our city apartment and we are in our upstate home without all our usual Passover paraphernalia, and I miss it terribly. The English cutlery I inherited from my parents and only use this special week will stay in its locked cabinet. The elegant Elijah’s cup my late father gave me on the shelf. I won’t bring out the plague puppets and noisy toy frogs I’ve collected over the years for children’s entertainment, nor the colorful matzo covers the kids made in day school.

These precious objects represent the holiday, but they are not its essence.

I used to spend hours setting the table. It will take a mere moment when we sit down on Wednesday night, just the two of us.

And so what? I cannot lament the loss of things when all around us people are losing lives and loved ones. We still have the Seder. We still have the story.

The questions raised by the Exodus story, recounted in the Haggadah, take on added urgency and relevance in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. What does it mean to be free when we are confined? How do we maintain our identity and our communal associations in isolation? How do we nourish hope when we may well face the modern-day equivalent of wandering the desert for forty more years?

The Haggadah is infused with gratitude to God for enabling an oppressed people to break free. Many of us are grateful simply to breathe each morning. What are we learning about ourselves? How will we make our society healthier, kinder and more just when this is finally over?

I’ve never experienced a Passover of such hardship, but the Jewish people have endured worse, and there’s comfort in knowing that.

I fervently hope we will gather next spring, that I will fuss about the price of brisket and the state of my matzo balls, that I will spend hours setting the cutlery and decorating the table with all the items I’ve collected, that we will study the text and dream of drawing new meanings from it.

It won’t be the same, because we won’t be the same. Once we have had to focus on the essence of the holiday, we will know that what matters most is the story we recite year after year, together.

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

As published in Columbia Journalism

#WhenThisIsOver I’ll Actually Appreciate Matzo

Jane R. Eisner | jre17@columbia.edu

It is known as the “bread of affliction” for good reason. Matzo, the unleavened flatbread that Jews eat during the week of Passover in place of bread and other leavened food, is intended to remind us of hardship and flight. The ancient Israelites baked this bread quickly, before it had time to rise, as they hastily prepared to leave Egypt for their long march to freedom.

With a texture like corrugated cardboard and a taste to match, matzo is the bane of anyone trying to keep a home clean during this holiday. It crumbles as easily as Donald Trump’s ego, and leaves such an unappetizing mess that even our dogs wouldn’t touch it when it sprinkled on the floor.

Around this time in the holiday cycle — day five, or so — I would usually tire of eating this mandated mouthful. Really, how many times could I melt cheese on a matzo sheet and pretend I was eating a gourmet sandwich?

But the experience of this Passover has turned my hardened heart into a grateful one. Matzo, I now realize, is the perfect pandemic pantry item.

It lasts, well, forever. (I never understood the notion of “fresh matzo.” How could it taste less stale?)

It can be combined with other stay-at-home staples — eggs for matzo brei, peanut butter for something sticky, jam for something sweet, melted chocolate for something really sweet. In the morning, I break it up in tiny pieces, dry roast it on the stove, add raisins and nuts, and voila — an ersatz granola that will never see its expiration date.

The bread of affliction has become the manna of rescue. I used to scoff at my husband when, during the year, he kept an extra box of matzo to use in an emergency. No more. #WhenThisIsOver, I will appreciate that crumbly cracker anew. And I’ll think twice before ever buying bread again.