Becoming an Adult at Temple Emanu-El

NEW YORK - “We are on the corner of Fifth and 65 Street in 2024. But now, we are going back to Mount Sinai,” Rabbi Sarah Reines said from the pulpit of Temple Emanu-El during a Shabbat service.

For at Mount Sinai, said Reines, Moses received a sacred scroll that would be passed down through the generations.

This was the cue for 13-year-old Gavin Matlin, who up until this point had been sitting in a chair to the right of the ark, wearing a suit and a tallit, his feet dangling a few inches above the floor. Gavin stood and moved to the front of the bimah.

Reines pulled open the doors of the ark and retrieved the Torah while Gavin’s family — his sister, parents and grandparents, all dressed in trim black suits and dresses — ascended the stairs to the bimah and lined up next to him.

“This is the Torah, a light for our eyes, a lamp for our way,” sang the congregation.

“Our ancestors roamed that desert so many thousands of years ago and they were given this great gift,” Reines said, carrying the Torah scrolls wrapped in a mantle of red velvet with gold tassels. “And you are all here now because someone in your family line loved Judaism and loved their children enough to pass on this gift. Gavin, now it comes to you.”

Reines presented the Torah to Gavin’s grandfather, who, in a sign of veneration, extended a hand to grasp the velvet mantle. Reines stepped forward to the boy’s grandmother, who did the same. The rabbi walked down the line of family, pausing so that each member could touch the Torah.

And so, from generation to generation, the Torah was handed down to Gavin on his Bar Mitzvah.

When the scrolls reached Gavin, he seemed to take in the weight of all that was wrapped in the mantle before him — physically, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible are contained in the scrolls, but in a broader sense, Jewish law and tradition and Matlin’s responsibility to the Jewish community are also there.

After a moment’s pause, he reached out to touch the mantle, before turning and springing toward his sister in a hug.

The boy, a boy no longer in Jewish eyes, embraced each member of his family and walked side by side with Reines to the pulpit, where he read a Torah portion from the Book of Exodus and gave a short speech. Reines then welcomed him as an adult member of the congregation.

A Sacred Moment Between Rest and Work: Havdalah at a Modern Orthodox Synagogue

NEW YORK — In 1941, a group of 61 Jewish refugees from Luxembourg arrived in New York City. Narrowly escaping the impending doom of Nazi-orchestrated extermination camps in East Germany, the group fled to Lisbon, then sailed across the Atlantic to seek refuge in the United States.

Despite pressures to assimilate fully into American culture, the refugees clung to their traditions, their community and their faith. The rabbi who coordinated their escape, Dr. Robert Serebrenik, found a half-completed Unitarian Church on the Upper West Side at 550 W 110th St. The church construction had been abandoned, and Serebrenik saw an opportunity. He purchased it and named the new synagogue Ramath Orah, “mountain of light” in Hebrew — a direct translation of Luxembourg, the home they had left behind.

In the looming space, the community gathered to pray, sing and eat. They rested from Friday evening to Saturday evening for Shabbat, and around sundown on Saturday, held maariv and havdalah to prepare for the week of work ahead.

Today, more than 80 years after the founding of the synagogue, those traditions continue. As the sun was setting on a recent Saturday evening, a 16-year-old named Ziv Siegel lights a thick white candle for Havdalah. Organ pipes from the unfinished church line the walls behind him, and the last rays of sunlight filter through a circular yellow and blue stained glass window gifted to the congregation by the government of Luxembourg.

Ziv begins to sing, and the small congregation who had gathered in the room, men and women separated by a cloth divider, joins in.

Baruch atah, Adonai Elohenu

Melech haolam

Borei p’ri hagafen

The melody is chillingly beautiful and drifts up to the high arching ceilings of the synagogue. The candlelight flickers on Ziv’s eyelids as he sings, his head bent down.

Congregants gather around him to observe the candlelight on their hands, flipping their palms back and forth and bending their fingers as if to beckon the light. The motion is a reminder of the light in the week and in life. To Ziv, this marks a departure from Shabbat, because lighting a candle is work that is forbidden during the prior day.

Ziv drinks the cup of wine, which seems to actually be grape juice, as a metaphor for the sweetness of the day of rest. Congregants sniff white mesh drawstring pouches filled with spices — one person says it’s cinnamon and cloves, another has no idea but says it smells nice — which fill the nostrils with a rich, earthy essence. During Shabbat, according to Ziv, the Talmud says a new soul comes to the body — a soul that brings peace, calm and rest. During havdalah, that soul departs. In order to rejuvenate the dormant souls tasked to work throughout the week, congregants smell the decadent spice. So begins the week ahead.

After Havdalah, Ziv and his father, Jonathan Siegel, say that the ceremony is a separation between holy time and the everyday. Ziv, who commutes an hour to an Orthodox Jewish school in Riverdale every day, says he feels deeply connected to the synagogue and the community. “It’s a lot of pressure,” he says about leading Havdalah. But the ritual, a quiet acknowledgement of the dichotomy of work and rest, peace and chaos, has given congregants over the decades a moment to acknowledge the passage of time, from the refugees who fled certain death in Europe to young practitioners like Ziv who are keeping their memories alive.

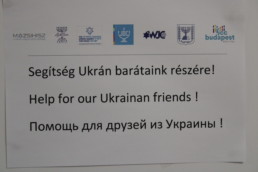

Fleeing War, a Ukrainian Flock Arrives in Budapest

The spirit of Moses shepherds displaced Christians and Jews nearly 4,000 years later

BUDAPEST — It is not yet 10 in the morning when the Ukrainian refugee children, many of them accompanied by their mothers and grandparents, enter through the main doors of the Jewish Community Center in downtown Budapest. They are welcomed by volunteers from Israel, who are costumed in tunics and fake beards. One Israeli college-aged girl, Yona Michal, is dressed as Moses. She is about to perform a play on the Book of Exodus, where Moses saves the Jews from slavery in Egypt and the armies of the Pharaoh.

Less than one mile away in the 1,000-year-old Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a priest reads a different part of the Moses story. He recounts Chapter 21 of the Book of Numbers, when Moses was struggling to keep the wandering Israelites on the path, both physical and spiritual, laid out for them by God. The priest used this tale to emphasize the importance of keeping the faith in bleak moments, that God would heal them if only they looked to him for help.

In both instances, Moses acted as a shepherd to the faithful as they sought a new home after fleeing violence in their previous one. In Budapest, religious nonprofits are taking on the role of Moses, acting as a shepherd to Ukrainian refugees fleeing Vladimir Putin’s war.

Less than three months earlier, on Feb. 24, Putin began a brutal military campaign bombing multiple cities in Ukraine, including the capital, Kyiv. Since the invasion, almost 5 million people have left their homes, according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Out of those 5 million, 530,000 have registered with the Hungarian government.

“We have joined forces to help refugees in any way we can, providing accommodation, clothing, supplies, whatever they need,” Marcel Kenesei, director of the JCC in Budapest said about the Jewish community’s contribution to Hungary’s response to the refugee crisis. “We also organize programs and we help them go to other countries like Israel or other European countries.”

While Kenesei speaks, an Israeli volunteer dressed up like a clown – complete with a red nose and rainbow-colored wig – is sitting down making balloon animals for young children around a plastic table at the JCC. The children squeal as the balloon slowly forms into its shape, and then deflates. As they play, most of their parents are sitting together, talking in hushed tones.

Kenesei estimates that the JCC has provided housing accommodation for 2,000 people just like the ones at the center that day, and resources to tens of thousands more. However, he said many do not stay in Budapest. Instead, they only spend a couple of days before flying to Israel.

“To get Israeli citizenship, that was an obvious choice for a lot of people,” Kenesei said. “The state of Israel decided to make it easier for Jews to enter, but the state of Israel decided to let non-Jewish people into Israel, so that’s an important piece of it.”

This crisis has caused a ripple effect of participation and activism within the Jewish community that Kenesei has never seen before. He said the JCC has worked with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish Agency and the Hungarian Jewish Federation.

“Organizations who have basically never spoken to each other, not to mention working together. They are the joint forces and cooperate in this crisis,” Kenesei said.

Many Ukrainian Jews, like Lyubov and her four-year-old daughter, Daniel, who withheld their last names for privacy reasons, do not want to stay in Budapest. Instead, they hope to travel to Israel where, according to Lyubov, it feels safer and there are no bombs. She chose Budapest instead of Poland, due to overcrowding.

New arrivals, Kenesei said, first go to the Budapest Olympic Center — called “BOK” by locals — an arena just 10 minutes from the nearest train station. There, they can get a warm meal, travel information and basic medical care. When the first bomb hit Kyiv eight weeks ago, government assistance for refugees fleeing to Budapest was practically non-existent.

Csaba Szabo, a member of the Catholic aid organization Caritas – the Latin word for “charity” – recalls the first few days of the crisis after Russia’s first airstrikes, how their expectations did not align with the real needs of the refugees.

Szabo agreed with Kenesei and said many aid organizations expected the incoming Ukrainians to seek shelter in Hungary until the end of the war. In reality, many Ukrainians chose to only stay in Budapest for a day or two before going elsewhere. The hotels and houses meant to shelter them went unused, and many of the first refugees had to sleep in a cold train station while they planned the next leg of their journey.

“The [relief center at the] stadium is a result of all the lessons we learned from those first days,” Szabo said.

Departure times for buses to the train stations are projected onto the wall in the stadium, as tall as the black and white banners honoring past Hungarian Olympic gold-medalists that stood next to them. Waiting areas are segregated by destination and marked out in Hungarian, Ukrainian and English. After the volunteers realized how many refugees fled with their four-legged companions, they set aside a roughly 100-foot square area for pet supplies.

The volunteers at BOK reported to Szabo that common language is the biggest issue they currently face. Many of the Ukrainians who could speak Hungarian came from the western border regions and arrived in the first few days, and have already left the city for their final destination elsewhere in Europe or in Israel, he said.

Now, new arrivals are coming from further East in Ukraine, Szabo said, and are unlikely to speak Hungarian at all, much less understand it well enough to navigate an unfamiliar city.

Szabo said finding volunteers who speak both Ukrainian and Hungarian are rare.

“Our job is different when we have the translators here,” he said.

According to Szabo, the language barrier has already caused misunderstandings about what documentation refugees need in order to receive aid. When translators are not available, aid workers must rely on English as a common language. For Jewish aid organizations, Kenesei said that Hebrew is often used instead.

Language is not the only reason Ukrainians are not keen to stay. Hungary leans towards authoritarianism, with a political system described as “illiberal democracy.” It is the only European Union nation to be rated as “partly free” by the media watchdog Freedom House.

A source who requested anonymity out of fear of government retaliation said that any entity that receives government funding is unable to talk about politics publicly, or they might lose their funding – or worse, become a target of the state-backed media.

Aid organizations cannot simply forgo government funding. A package of laws from 2018 requires any organization that aids migrants to secure a license from the government in order to operate. Doing so without a license can result in tax audits, investigations and fines, putting aid organizations in a bind.

This at least allows religious aid organizations to give more extensive care to the refugees that do arrive.

One of these aid organizations is the Jewish Charity Hospital, located just miles away from BOK, on the Pest side of the city. A couple exits on the highway away, the hospital is nestled next to a Jewish day school, surrounded by trees just beginning to grow leaves after a long winter.

In the lobby of the hospital, glass doors open to a recently renovated white tiled entryway. Even with the doors shut, the sounds of young children playing at recess combined with the high-pitched clicking of nurses’s shoes filled the hallway.

After the Holocaust, Stalinism and the state-mandated atheism of the Soviet Union, the Jewish Charity Hospital in Budapest is the only Jewish hospital left in Europe.

One of its patients, a Hungarian Jew named Pal Fezekas, is a Holocaust survivor. He spent the war hiding in the attic of a French aristocrat in Paris, where he was born. Now, Fezekas lives in a room with three other men on the second floor of the hospital. In his bed, he keeps cigarettes and his cell phone.

Downstairs, in the middle of the afternoon, Fezekas sat in a wheelchair, chain-smoking his cigarettes in the parking lot of the hospital. He said out loud what many were afraid to say – what is happening right now with Putin and Ukraine does not feel much different than what happened back then.

“The war is the continuation of the wars that happened in the twentieth century. There is war, always some war in the world,” he said. “I was five years-old when World War II ended, a kid like that does not really understand what a war means, especially when you spend your life in a protected environment, and yet, I knew what was happening. I was very much aware.”

Fezekas said both Putin and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán are mass murderers. His comments are a result of not only Orbán’s hostility towards migrants, but also the support and apparent friendship between the two leaders. Orbán has personally supported Putin’s war by buying Russian gas and blocking military aid to Ukraine. After living in the hospital for the past two months with other Holocaust survivors, Fezekas said it was Orbán’s recent re-election that made him physically feel worse.

As Fezekas spoke, he pointed at his recently amputated right leg, tied up in a pair of white-turned-gray pajama pants to emphasize how his physical health has been impacted by the beginning of Orbán’s fourth consecutive term.

The Jewish Charity Hospital, where Fezekas lives, has also provided medical resources for the Ukrainian refugees since the war began in February. The hospital’s CEO, Dr. Assaf Shemesh, estimated that it has provided medical care to more than twenty Ukrainian patients a day.

Shemesh told one story, while sitting at his desk in his top floor office overlooking the parking lot Fezekas was in, about a hotel where many refugees are living that had a gastroenteritis outbreak. Some children became so dehydrated they had to be sent to the Emergency Department. The hospital also struggled to fill prescriptions for medications that are available in Ukraine, but not approved in European Union countries, including Hungary.

“Mostly the people coming to our clinic are very old and very exhausted,” Shemesh said. “They didn’t want to go to Israel, but now they have no other chance. They have nowhere to go back to.”

Lyubov and her young daughter are among the millions of displaced people, wandering through a complex and foreign system while searching for a new home. Some, like the Israelites in the Bible, want to reach their promised land as soon as possible, despite the danger. Lyubov hopes to stay in Budapest while she gets her and Daniel’s travel documents sorted out, which can take weeks. Either way, refugees must rely on the continued help of religious aid organizations like the JCC and Caritas.

“You know, it’s difficult to say because of course she’s enjoying Hungary” Lyubov said of her daughter. “ It’s a very beautiful city but we changed four countries in two days.” Ultimately, she added, her daughter “needs stability, and she needs a home.”

Lyubov has little left to hang onto except what she could carry with her from Ukraine. Despite the differences in language, culture and heritage, there is at least a shared experience of hearing the scripture and finding comfort in the story of Moses.

How the Synagogue Hostage Crisis Changed the DNA of Colleyville, Texas

As Congregation Beth Israel reopens, interfaith efforts deepen and houses of worship intensify security measures, adapting to “a more violent world.”

COLLEYVILLE, Texas – On Jan. 15, Colleyville, a small suburb just miles from the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, was thrust into the national spotlight as a gunman, armed with a pistol, took four people hostage for 11 hours in the Congregation Beth Israel synagogue. All four hostages escaped unharmed before the suspect was shot, authorities said. The FBI labeled the incident as a terrorist act and hate crime.

But this acutely religious North Texas town with 28 houses of worship in its 13 square miles, did not retreat in fear and suspicion. Instead, it reconceived of the terror attack as a beacon of hope. Since the live-streamed standoff, religious leaders in Colleyville mobilized to ensure the safety of their believers and buttress the area’s robust interfaith system.

After nearly three months, the synagogue, which has been closed as a crime scene, is reopened to its 150 members on April 9. Since the incident, the congregation was hosted by the First United Methodist Church of Colleyville, one mile away. Now that it is back in its home, Congregation Beth Israel will have a police presence at every event. For Colleyville’s Jewish believers like Howard Rosenthal, former president of the Beth Israel Congregation, restarting services in the synagogue with reinstalled bulletproof windows feels like “moving forward.”

Interfaith activists in Colleyville, which is overwhelmingly comprised of Christians, said they want to set the record straight, referring to what they call the town’s mischaracterization in national press outlets. The scandals plaguing Dallas-Fort Worth have garnered media attention after the 2021 Capitol insurrection (which involved residents from DFW) and last year’s Critical Race Theory controversies at Colleyville public schools. Despite North Texas stereotypes, 21 religious community groups have been building interfaith bridges for four years under the umbrella of Peace Together, which was founded after racial and religious tensions unleashed at a 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, N.C.

“We will have a safe, loving and committed community so we can go forward and not focus on the past,” said Rosenthal.

Having lived in DFW for 19 years, Rosenthal leads Peace Together and organized interfaith healing ceremonies after Jan. 15. Rosenthal was teary-eyed while recalling how interfaith leaders rushed in to help during and after the crisis.

As Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker of Congregation Beth Israel wrote in The New York Times:

“My congregation and I received an outpouring of love and support from strangers. If we begin with that love of the stranger, but offer it not in response to violence, but encouraged by empathy, we might just change our world.”

Everyone from Muslims to Catholics to Mormons stepped up. The Colleyville Texas Stake of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a member of Peace Together, has a deep respect for people who worship in different ways because Mormons have a history of persecution, said Leslie Horn, the Media Specialist at the church. Horn described Jan. 15 as a defining violation for her church. Still, the subsequent press coverage “missed a lot of the good,” she said.

“In Texas, there tends to be this belief that we aren't diverse in thought, people and faiths,” Horn said. “But if you've spent any time living here, you quickly realize that’s not true. If you know anything about interfaith work, you know Colleyville is a leader.”

Horn said she could not fathom the juxtaposition of savagery in a sacred space. Horn, like so many religious observers in Colleyville, found herself in disbelief and kept asking herself, “Why Colleyville?”

Rev. Michael Higgins, the senior priest at Good Shepherd Colleyville, shared Horn’s shock. Even though the standoff was “hectic and surreal,” Good Shepherd Colleyville jumped into action. For ten hours during the standoff, Higgins’ church, just one block away from the synagogue, hosted the press, the four spouses of the hostages and the local police. After the dust settled, Good Shepherd continues to seriously consider beefing up its security measures, said Higgins. Still, he refused to cancel Sunday services the next day, opting to pray for the town.

“Despite all the evidence to the contrary, God loves us,” Higgins said.

It is unfortunate that an event like this would be the catalyst for the country to be introduced to Colleyville. But January 15, Higgins said, was an immediate rallying of all faith traditions, which brought to light the reality of the tight community in Colleyville. Higgins has led the interfaith alliance in Colleyville since 2020.

“We were just trying to be of service,” Higgins said. “This shouldn't be special.”

Abdul Rashid Khan, a founding member of Colleyville Masjid, said his house of worship is no stranger to the eerie sensation of looming danger. His gated mosque has had security since Sept. 11, 2001, and reactively increased its surveillance measures since Jan. 15. Khan, a friend to hostage Cytron-Walker and participant in interfaith meetings, said he could easily imagine a similar crime happening in his mosque. To cope and maintain hope, Khan has thrown himself into interfaith work.

“Our prophet Mohammed used to visit other religious spaces so that he could set an example of how his faith should be respected,” Khan said. “We follow that example.”

Katie Newkirk, a pastor at First United Methodist Church of Colleyville, reviewed her church’s safety policy after the “defining moment” of Jan. 15, installing new security systems and implementing training sessions for church staff. Still, she said Colleyville’s transformation in the past few months is twinged with optimism as local comradery has outshone religious differences.

“It’s been a beautiful time to come together,” Newkirk said. “I don’t think God causes bad things to happen, but God brings good outcomes from messed up situations.”

Learning Forgiveness in the Age of Cancel Culture

As the seventh Psalm wraps up, representing the seventh day of the week, the congregation at Stephen Wise Free Synagogue on 30 West 68th Street sits down. Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch approaches the front of the Bimah, where the Torah is read, to begin his weekly Friday night sermon.

Instead of focusing on a piece of scripture, Hirsch begins with a story from pop culture.

“I never met Whoopi Goldberg,” he began. “And I don’t watch The View.”

A couple members of the congregation reacted with nervous laughter at the mention of Goldberg in light of recent events. Hirsch waited a couple beats before continuing his speech. Earlier in the week, Whoopi Goldberg was suspended for two weeks from her daily talk show, The View, for saying that the Holocaust was “not about race” on air.

“Whoopi Goldberg said some truly offensive and ignorant things, but she apologized immediately and sincerely,” Hirsch said. “Repentance, forgiveness and atonement are central concepts in religion.”

As Hirsch spoke, his congregation nodded their heads slowly in agreement. They too believed that forgiveness is a crucial part of their worship and faith.

“Americans nowadays seem incapable of accepting apologies,” Hirsch continued.

For both the teacher and his students, the message was about how to face “cancel culture,” or the fear of societal backlash over a genuine mistake, as an observant Jew. Hirsch’s sermon used Goldberg’s offensive comment as an opportunity to talk about forgiveness and trust in God. Both of these tenets are core to Judaism, according to Hirsch.

Hirsch explained to his congregation that human nature resists wanting to own mistakes and apologize for them, emphasizing that “it is hard to do.”

Many quizzical looks filled the faces of Hirsch’s listeners then. If forgiveness was essential to their faith, but it was difficult to do, what were they supposed to do? Was there a way they could combat this human urge with their religion?

Hirsch had an answer: The High Holy Days.

According to Hirsch, the High Holy Days, also known as Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, are meant for repentance and forgiveness. In Hebrew, Rosh Hashanah means, “Beginning of the Year,” and Yom Kippur means “Day of Atonement.” Hirsch’s sermon focused on both the literal and spiritual meanings of each by explaining how to react and forgive Goldberg for her comment. Hirsch said he believes she should be forgiven because she genuinely apologized and atoned for what she said.

“Judaism is so insistent on contrition and forgiveness that our holiest season of the year, our highest of High Holy Days, is devoted to urging people to repent and forgive,” Hirsch said. “The reason we make such a big deal about it — ten full days of almost nonstop prayer and lamentation, beating our chests in sorrow — is that it is hard to do.”

Hirsch was teaching his worshippers to forgive Goldberg not because it is the easy thing to do, but because from his view, forgiveness is the right thing to do. The reason why forgiveness and acceptance are so important to human relationships is because without them, society will end up “nasty, brutish, violent and tribal,” Hirsch said.

Instead of using a reading or lesson from the Torah, which is the law of God as revealed to Moses and recorded in Hebrew, Hirsch used a news story to teach the Jewish values of forgiveness and atonement.

Cantor Daniel Singer explained that the Friday sermon is different from the Saturday sermon each week during Shabbat services. Singer said that the Rabbi, Hirsch, has never given the same sermon twice. At Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, the Torah is only read on Saturday and holidays, according to Singer.

Most Saturdays, the sermon or speech is given by a Bat or Bar Mitzvah, instead of Hirsch, after their Torah reading, Singer said. According to Singer, Hirsch draws from all areas of life for his weekly sermons, but enjoys preaching about Jewish heritage, history and social justice issues the most.