The spirit of Moses shepherds displaced Christians and Jews nearly 4,000 years later

BUDAPEST — It is not yet 10 in the morning when the Ukrainian refugee children, many of them accompanied by their mothers and grandparents, enter through the main doors of the Jewish Community Center in downtown Budapest. They are welcomed by volunteers from Israel, who are costumed in tunics and fake beards. One Israeli college-aged girl, Yona Michal, is dressed as Moses. She is about to perform a play on the Book of Exodus, where Moses saves the Jews from slavery in Egypt and the armies of the Pharaoh.

Less than one mile away in the 1,000-year-old Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a priest reads a different part of the Moses story. He recounts Chapter 21 of the Book of Numbers, when Moses was struggling to keep the wandering Israelites on the path, both physical and spiritual, laid out for them by God. The priest used this tale to emphasize the importance of keeping the faith in bleak moments, that God would heal them if only they looked to him for help.

In both instances, Moses acted as a shepherd to the faithful as they sought a new home after fleeing violence in their previous one. In Budapest, religious nonprofits are taking on the role of Moses, acting as a shepherd to Ukrainian refugees fleeing Vladimir Putin’s war.

Less than three months earlier, on Feb. 24, Putin began a brutal military campaign bombing multiple cities in Ukraine, including the capital, Kyiv. Since the invasion, almost 5 million people have left their homes, according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Out of those 5 million, 530,000 have registered with the Hungarian government.

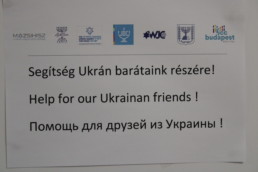

“We have joined forces to help refugees in any way we can, providing accommodation, clothing, supplies, whatever they need,” Marcel Kenesei, director of the JCC in Budapest said about the Jewish community’s contribution to Hungary’s response to the refugee crisis. “We also organize programs and we help them go to other countries like Israel or other European countries.”

While Kenesei speaks, an Israeli volunteer dressed up like a clown – complete with a red nose and rainbow-colored wig – is sitting down making balloon animals for young children around a plastic table at the JCC. The children squeal as the balloon slowly forms into its shape, and then deflates. As they play, most of their parents are sitting together, talking in hushed tones.

Kenesei estimates that the JCC has provided housing accommodation for 2,000 people just like the ones at the center that day, and resources to tens of thousands more. However, he said many do not stay in Budapest. Instead, they only spend a couple of days before flying to Israel.

“To get Israeli citizenship, that was an obvious choice for a lot of people,” Kenesei said. “The state of Israel decided to make it easier for Jews to enter, but the state of Israel decided to let non-Jewish people into Israel, so that’s an important piece of it.”

This crisis has caused a ripple effect of participation and activism within the Jewish community that Kenesei has never seen before. He said the JCC has worked with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish Agency and the Hungarian Jewish Federation.

“Organizations who have basically never spoken to each other, not to mention working together. They are the joint forces and cooperate in this crisis,” Kenesei said.

Many Ukrainian Jews, like Lyubov and her four-year-old daughter, Daniel, who withheld their last names for privacy reasons, do not want to stay in Budapest. Instead, they hope to travel to Israel where, according to Lyubov, it feels safer and there are no bombs. She chose Budapest instead of Poland, due to overcrowding.

New arrivals, Kenesei said, first go to the Budapest Olympic Center — called “BOK” by locals — an arena just 10 minutes from the nearest train station. There, they can get a warm meal, travel information and basic medical care. When the first bomb hit Kyiv eight weeks ago, government assistance for refugees fleeing to Budapest was practically non-existent.

Csaba Szabo, a member of the Catholic aid organization Caritas – the Latin word for “charity” – recalls the first few days of the crisis after Russia’s first airstrikes, how their expectations did not align with the real needs of the refugees.

Szabo agreed with Kenesei and said many aid organizations expected the incoming Ukrainians to seek shelter in Hungary until the end of the war. In reality, many Ukrainians chose to only stay in Budapest for a day or two before going elsewhere. The hotels and houses meant to shelter them went unused, and many of the first refugees had to sleep in a cold train station while they planned the next leg of their journey.

“The [relief center at the] stadium is a result of all the lessons we learned from those first days,” Szabo said.

Departure times for buses to the train stations are projected onto the wall in the stadium, as tall as the black and white banners honoring past Hungarian Olympic gold-medalists that stood next to them. Waiting areas are segregated by destination and marked out in Hungarian, Ukrainian and English. After the volunteers realized how many refugees fled with their four-legged companions, they set aside a roughly 100-foot square area for pet supplies.

The volunteers at BOK reported to Szabo that common language is the biggest issue they currently face. Many of the Ukrainians who could speak Hungarian came from the western border regions and arrived in the first few days, and have already left the city for their final destination elsewhere in Europe or in Israel, he said.

Now, new arrivals are coming from further East in Ukraine, Szabo said, and are unlikely to speak Hungarian at all, much less understand it well enough to navigate an unfamiliar city.

Szabo said finding volunteers who speak both Ukrainian and Hungarian are rare.

“Our job is different when we have the translators here,” he said.

According to Szabo, the language barrier has already caused misunderstandings about what documentation refugees need in order to receive aid. When translators are not available, aid workers must rely on English as a common language. For Jewish aid organizations, Kenesei said that Hebrew is often used instead.

Language is not the only reason Ukrainians are not keen to stay. Hungary leans towards authoritarianism, with a political system described as “illiberal democracy.” It is the only European Union nation to be rated as “partly free” by the media watchdog Freedom House.

A source who requested anonymity out of fear of government retaliation said that any entity that receives government funding is unable to talk about politics publicly, or they might lose their funding – or worse, become a target of the state-backed media.

Aid organizations cannot simply forgo government funding. A package of laws from 2018 requires any organization that aids migrants to secure a license from the government in order to operate. Doing so without a license can result in tax audits, investigations and fines, putting aid organizations in a bind.

This at least allows religious aid organizations to give more extensive care to the refugees that do arrive.

One of these aid organizations is the Jewish Charity Hospital, located just miles away from BOK, on the Pest side of the city. A couple exits on the highway away, the hospital is nestled next to a Jewish day school, surrounded by trees just beginning to grow leaves after a long winter.

In the lobby of the hospital, glass doors open to a recently renovated white tiled entryway. Even with the doors shut, the sounds of young children playing at recess combined with the high-pitched clicking of nurses’s shoes filled the hallway.

After the Holocaust, Stalinism and the state-mandated atheism of the Soviet Union, the Jewish Charity Hospital in Budapest is the only Jewish hospital left in Europe.

One of its patients, a Hungarian Jew named Pal Fezekas, is a Holocaust survivor. He spent the war hiding in the attic of a French aristocrat in Paris, where he was born. Now, Fezekas lives in a room with three other men on the second floor of the hospital. In his bed, he keeps cigarettes and his cell phone.

Downstairs, in the middle of the afternoon, Fezekas sat in a wheelchair, chain-smoking his cigarettes in the parking lot of the hospital. He said out loud what many were afraid to say – what is happening right now with Putin and Ukraine does not feel much different than what happened back then.

“The war is the continuation of the wars that happened in the twentieth century. There is war, always some war in the world,” he said. “I was five years-old when World War II ended, a kid like that does not really understand what a war means, especially when you spend your life in a protected environment, and yet, I knew what was happening. I was very much aware.”

Fezekas said both Putin and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán are mass murderers. His comments are a result of not only Orbán’s hostility towards migrants, but also the support and apparent friendship between the two leaders. Orbán has personally supported Putin’s war by buying Russian gas and blocking military aid to Ukraine. After living in the hospital for the past two months with other Holocaust survivors, Fezekas said it was Orbán’s recent re-election that made him physically feel worse.

As Fezekas spoke, he pointed at his recently amputated right leg, tied up in a pair of white-turned-gray pajama pants to emphasize how his physical health has been impacted by the beginning of Orbán’s fourth consecutive term.

The Jewish Charity Hospital, where Fezekas lives, has also provided medical resources for the Ukrainian refugees since the war began in February. The hospital’s CEO, Dr. Assaf Shemesh, estimated that it has provided medical care to more than twenty Ukrainian patients a day.

Shemesh told one story, while sitting at his desk in his top floor office overlooking the parking lot Fezekas was in, about a hotel where many refugees are living that had a gastroenteritis outbreak. Some children became so dehydrated they had to be sent to the Emergency Department. The hospital also struggled to fill prescriptions for medications that are available in Ukraine, but not approved in European Union countries, including Hungary.

“Mostly the people coming to our clinic are very old and very exhausted,” Shemesh said. “They didn’t want to go to Israel, but now they have no other chance. They have nowhere to go back to.”

Lyubov and her young daughter are among the millions of displaced people, wandering through a complex and foreign system while searching for a new home. Some, like the Israelites in the Bible, want to reach their promised land as soon as possible, despite the danger. Lyubov hopes to stay in Budapest while she gets her and Daniel’s travel documents sorted out, which can take weeks. Either way, refugees must rely on the continued help of religious aid organizations like the JCC and Caritas.

“You know, it’s difficult to say because of course she’s enjoying Hungary” Lyubov said of her daughter. “ It’s a very beautiful city but we changed four countries in two days.” Ultimately, she added, her daughter “needs stability, and she needs a home.”

Lyubov has little left to hang onto except what she could carry with her from Ukraine. Despite the differences in language, culture and heritage, there is at least a shared experience of hearing the scripture and finding comfort in the story of Moses.