‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

As published in the Columbia News Service

‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

Lily Lopate

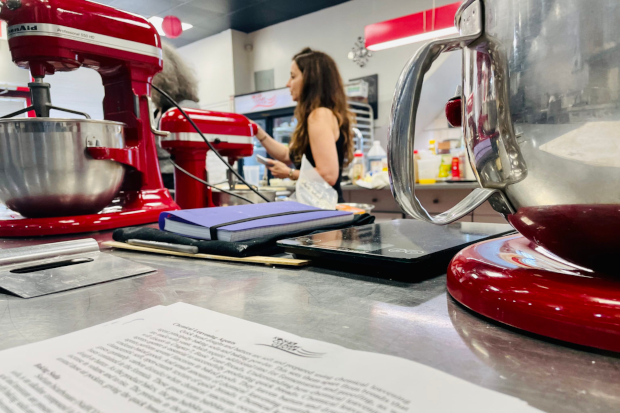

Kosher cooking has a lot of rules, but that doesn’t mean that learning kosher cooking isn’t fun. During a pastry workshop at the Kosher Culinary Center in Brooklyn in July, the students — six women, one teenage boy and one man — were tasting bite-sized cocoa pear muffins that had just emerged from the oven. “These muffins are perfect for a ladies’ brunch, bridal shower or bris,” said Avram Wiseman, 64, the Center’s co-founder and chef. As the class inspected the flecks of melted chocolate and grated pears, the teenage student looked despondently at a muffin that overflowed in the baking tray. Wiseman noticed. “What do we do with our mistakes?” he asked. “We eat them!”

There’s plenty of humor at the Kosher Culinary Center, especially since it reopened to full capacity cooking classes this summer. Located in Sheepshead Bay, between Marine Park and Mill Basin, the center offers recreational cooking classes, a catering business and a professional culinary training program.

Because people experience faith at varying degrees, the center’s aim is inclusivity, and its students make up an eclectic mix of Orthodox, Conservative and Reconstructionist Jews. “We cater to everyone regardless of how religious they are,” said the center’s director and co-founder, Perline Dayan, 53. “One does not need to have knowledge of kashrut laws prior to starting our program.”

This attempt to create common ground, through food, among segments of the Jewish population that may otherwise be isolated from each other has made the center a place for members of the Jewish Brooklyn community to connect or reconnect. Recreational and professional classes are open to men and women, ages 16 and older. And things are getting busy again now that in-person gatherings are less restricted than they were last summer. “Once people got vaccinated, our class size shot up,” said Dayan.

The increased number of students has inspired the school to apply for full accreditation, which would grant it an added degree of recognition as an educational institution. It’s currently the only trade school licensed by the state of New York to teach the skills needed to work in the kosher food industry.

In addition to its classes, the center’s also seen an increase of customers who book the venue for social events. People come for Jewish Singles Night or Culinary Date Night. “The date nights always fill up fast,” said Dayan. “A few couples meet for the first time and make a signature cocktail, kalamata olive focaccia and the chef’s choice of hors d’oeuvres.” The center has also resumed catering for large party events up to 50 people, a significant increase from the 10-person average last summer.

The center certainly has the look of a place where serious cooking happens. In the airy, industrial-sized teaching kitchen are red cupboards filled with baking tools, large pieces of cookware hang from a pot rack that wraps around the ceiling and students wearing black aprons work at long silver tables. A Star of David and printouts of Hebrew prayers are taped to the entryway wall. Opposite the sink, a framed plaque displays the kosher certification signed by two rabbis from the Northern American Kosher Supervision. If it weren’t for these hints of Judaism, the Kosher Culinary Center — which founders say is the only school outside of Israel to offer professional training in the kosher culinary arts — looks just like any professional cooking school.

Wiseman’s classes are the most popular, said Dayan. “Students love him,” she said. It is easy to see why: his sense of humor and playfulness in the kitchen allows him to quote apt lessons from the Torah as he’s teaching. In a class on “quick dry breads,” Wiseman asked, “What is the origin of unleavened bread?” And when students answered “Passover,” he explained further. “When Pharoah agreed to let the Israelites go, they hurried out of Egypt. They were in such a hurry they could not let their bread rise all the way so they took it with them just as it was starting to rise. So, there you go — quick bread.”

Wiseman teaches classes in both the professional and recreational tracks. Recreational classes are shorter and focus on one theme, like breads, desserts or meats. Professional classes are much more intensive. They include 216 hours (or 54 days) of hands-on training in technical professional skills and techniques. Courses last 11-16 weeks, and participants must enter with a high school diploma or equivalent degree to obtain a certificate from the culinary program. Students are drilled on how to cook safely and skillfully in a kosher environment, and the course’s difficulty escalates from knife skills to breads, starches, stocks, fish and meat.

The school also provides counseling, networking opportunities and interview preps to help students make the transition into a full-time culinary job. Come the end of the term, students in the professional classes must take a final exam to test their knowledge of kosher rules.

Before co-founding the center with Dayan in 2015, Wiseman had been teaching for several years, most recently at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts in Brooklyn, which closed in November 2015. He had also worked in a variety of settings, including the United Nations, where he was the executive sous chef. In that role, he said, “I cooked for several presidents: Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon. Each one had their quirky favorites.” He also cooked there for Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen.

Though he keeps kosher, Wiseman’s years in the culinary industry were spent cooking in non-kosher kitchens at a large, restaurant scale. His vast career network allows him to connect students with colleagues in the industry. “I’m doing this so people can gain a parnassah [the tools to make a decent living],” Wiseman said. It’s a way of passing on the trade through generations.

Dayan met Wiseman when she took a class of his in 2013 at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts. “It opened up a whole new world. I had never tasted a beet before,” she said. Dayan, like many of Wiseman’s students, is a career switcher. After years working in the trading firm Ladenburg Thalmann and Co., she wanted a change.When the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts was forced to close because it was operating without a license, Wiseman and Dayan decided to form a partnership. “I come from accounting and he’s a professional chef,” she said. “We decided to start our own school.”

Their vision was to create a modern twist on kosher cooking. “We do traditional Jewish foods, but we do them with style,” said Wiseman. “It’s not your mother’s potato latkes. We make it gourmet.” To stay relevant, they also teach a range of global cuisines including French, Italian, Vietnamese and Greek. Recently, at the request of one student, Sephardic dishes were added such as cassola (sweet cheese pancakes), buñuelos (puffed fritters with an orange glaze), keftes de espinaka (spinach patties), and keftes de prasa (leek patties).

For Dayan, an observant Jew, the kosher component was critical to the partnership. “If it wasn’t going to be a kosher school then I wouldn’t be here,” she said. To be fully compliant as “kashrut” (kosher), the kitchen must be supervised by a rabbi, and a certified “mashgiach” (the kitchen supervisor), must always be present. The kashrut rules are strict and unyielding: no meat can coexist with dairy in the kitchen and even meat and dairy utensils must be separated. Recently, a younger student entered class with a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and, when asked whether it contained milk, was directed to go outside and immediately throw it away. It is common practice to toss out or “tear” food that is out of order. (The Yiddish word “treif” derives from the Hebrew word for torn).

Across the spectrum of Judaism, the level of piety in the kitchen may vary. A nostalgic relationship to Jewish cuisine is sometimes described derisively as “Kitchen Judaism,” referring to Jews for whom religion revolves mainly around food. At the center, the connection between faith and food is clearer. “There’s more to Judaism than just being Jewish and cooking at the same time,” said Dayan. “So, if we have someone who is new to Judaism, we educate them on aspects of the religion.”

But regardless of the degree of piety, once students come to the center, they are part of the “whole mishpachah” (family) as Leah Waronker, a recent high school graduate and volunteer at the center, described it. “To cook kosher is to have faith in Judaism,” she said. “There’s a real intimacy that comes from working inside this community. From the moment I first put on my apron, I was welcomed with warmth. I literally fell in love.”

Back in the kitchen classroom, the smell of baked apple and cinnamon fills the room as the students begin preparing country-style biscuits. “Gentlemen,” Wiseman said to the two males in the class, “when you’re working with the flaky dough, bring out your feminine side. Be tender.” If the dough lacks moistness, he recommended more kosher butter (a non-dairy substance akin to margarine). “We grab the block of frozen butter, and we grate it like mozzarella cheese into the bowl. Now, we add vanilla. Say it with me,” he said, waving a wooden spoon like a conductor. The class recited the words after him “van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a.”

For Alla Dorch, an architect and student in the pastry class, baking kosher started as a peripheral activity and is now central to her life. “Cooking is usually something I do on the way to doing something else, you know?” she said. “I have my own design studio, so this started as something I could do with my family. But now I realize the crossover with architecture and pastry — both are very precise.” As Dorch’s interest in kosher culinary arts has grown, she is now considering starting a baking business. “It’s funny,” she said. “I used to go to synagogue to think about what comes next in my life. Now I come here.”

“The Whole Situation was Soaked in Love”

“The Whole Situation was Soaked in Love”

Lucy Soucek

When Hope Fried first received the text from her staff chaplain, she burst into tears. Pacing her Manhattan apartment, her mind was racing. It was spring of 2021 and she was working the on-call shift of her chaplaincy residency at nearby Mt. Sinai hospital. The message came in at around nine in the evening explaining that a mother in the labor and delivery unit was preparing to give birth to a baby either stillborn or expected to pass away soon after birth. The mother was Roman Catholic, Spanish speaking, and she was asking for her child to be baptized.

Fried, 32, is Jewish. Normally, she would have called for a Catholic priest to conduct the baptism, but this was during the overnight shift. If the baby was born alive and they waited for the priest to make it over to the hospital, they ran the risk that the baby might die before the priest arrived.

Fried wasn’t allowed at the hospital during the overnight shift because of Covid restrictions. She had never been to a Catholic baptism, and now she would have to talk a doctor or a nurse through one from her living room on the phone in Spanish in the middle of the night during a pandemic. After her initial bout of panic, she realized that she had a choice to make. And that choice was experienced by many chaplains over the past year and a half.

“COVID made it so that in the times where you would call for a priest or you'd try to call for an Imam, that wasn't available,” said Fried. “So it asked more of us because just the logistics weren't really possible. I think a lot of chaplains were like, okay, we just have to show up with our full humanity.”

In hospitals across New York City, pandemic restrictions have forced chaplains to navigate novel and potentially uncomfortable situations in their attempts to administer care. But what has guided them through the last year and a half is training that prepares them to honor the belief systems of their patients, even when those belief systems are dramatically different from their own. Now, chaplains and chaplain educators are focusing on how to care for themselves so that they can care for others as they continue to practice both in person and remotely.

For Fried, growing up in a multi-religious household influenced her eventual path to chaplaincy. Her mom is Catholic and her dad is Jewish. Ever since she was young, she’s felt more connected to Judaism, although she’s never had a strong belief in God. That’s where her humanism comes in. She identifies as a Jewish Humanist, which means she is ethnically Jewish, but in terms of spiritual beliefs, she doesn’t believe in a higher power.

When deciding what she wanted to pursue in her career, religion felt important. She thought, if she was meant to become a rabbi, God would reach out. But that just never happened. And so she turned to chaplaincy. It was a way for her to still feel connected with her faith, despite not believing in a higher power, and it allowed her to just sit with people and help them navigate hardships.

“I thought, ‘maybe I should try chaplaincy,’” said Fried. “It doesn't have to be super religious, but you get to be with people; you get to accompany people.”

She attended Union Theological Seminary, graduating in the spring of 2020. After taking four units of Clinical Pastoral Education to become board certified and participating in a yearlong residency. She is now a staff chaplain at the Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan.

It was during her residency that she navigated the baptism. And so on that night, Fried spoke with the doctor, who also happens to be Jewish, and they decided to make it happen. “We were both very firm,” Fried said. “I remember that feeling of being really grounded in our intention of like, we've been asked to do this; we are going to do this.”

After they made the decision, it was all about talking through logistics. Fried’s staff chaplain and clinical supervisor emailed her a guide to performing an emergency baptism, with details outlining the protocol, sample prayers and information on how to provide support over the phone.

She didn’t know Spanish, so she pulled up YouTube videos and practiced it with her husband over and over again, then walked the doctor through the ritual instructions on the phone. The doctor would need a little pill cup of sterilized water, which would act as holy water. Typically, holy water is water that has been blessed by a member of the clergy, but in the hospital, the protocol is different.

Dabble water on the baby’s forehead, and say:

“[Patient’s name,] Bautizo a ti en el nombre del Padre,” [I baptize you in the name of the Father].

Drop of water.

“y del Hijo.” [and the Son].

Drop of water.

“Y del Espiritu Santo,” [and the Holy Spirit].

Drop of water.

“Amen.”

The baby was born at around 4:30am, alive. A nurse performed the baptism, though Fried doesn’t know their personal religion or language preference. And then, at 4:45am, Fried called the on-call priest to come to the hospital to bless the baby and provide an official document. The baby survived for a couple of hours and then died later that morning.

In the Catholic church, baptism is seen as a way to cleanse infants from the original sin they were born with, and to welcome them into the Catholic faith. So Fried says the family was deeply appreciative that they were able to perform the ritual and receive the certificate.

“I think sometimes we attend to the worst moments in people's lives,” said Fried. “We try to be present and accompany and we try to lessen, slightly, their spiritual distress, and I think having their baby baptized was able to slightly lessen some of that spiritual distress.”

Throughout this whole situation was the tension between Fried’s Jewish Humanism and the Catholic ritual that she was being asked to lead someone through. But Fried, relying on what she learned about being a hospital chaplain where they often have to navigate interfaith situations, thinks of it as an expression of love.

“If a family has this request and this is their ultimate expression of love and will provide some sense of spiritual relief to know that their baby has been baptized and blessed by God and will be accepted into heaven, I think that's an ultimate expression of love and I will perform it,” said Fried.

Hospital chaplains navigate these complicated situations every day, but many also benefit from a system of training called Clinical Pastoral Education that is in place to guide them. During her yearlong residency, Fried was guided by her education supervisor, Rev. David Fleenor. He is the director of education for the Center for Spirituality and Health and the Assistant Professor of Medical Education at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai. He is also ordained as an Episcopal priest.

One idea that Fleenor, 46, taught Fried to keep at the forefront of her mind was to think about the context of the situation and how that determines her role as the chaplain. For Fried, the pandemic, the timing of the birth, the support she received from educators and other chaplains, and the importance of this ritual to the family all drove her decision to make sure it would happen.

“The whole situation was soaked in love,” Fleenor said. “People have their own convictions, but the beautiful work that she did was to dig deeper within herself and find that love was a deeper value; that love and care and compassion compelled her more to facilitate this meaningful ritual for this family, at such a profound time of loss in their life.”

Profound loss was ubiquitous throughout the pandemic. And hospital chaplains spent much of their time caring for not only patients and families, but staff as well. At Mount Sinai, chaplains had the option to administer care throughout the pandemic in person, and many did. Fleenor said their role of caring for staff at the hospital was vital and is too valuable for the field to be replaced by services done over the phone.

“What happens with chaplains is that they are embedded on units and they walk around and staff informally say, ‘Man I'm really struggling,’” said Fleenor. “They're not necessarily gonna reach out to the employee assistance program. But when the chaplain happens to be there, then they open up.”

But to be able to provide staff support, hospital chaplains also need to know how to take care of themselves.

At Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the staff chaplains were able to administer care in person throughout the pandemic, just not in the rooms of COVID-19 patients. Figuring out how to sustain care and avoid compassion fatigue is now one of their primary concerns.

“It’s like everyone's taking a vacation or is sick or something,” said Rev. Christine Davies, ordained Presbyterian minister and the director of pastoral care at Robert Wood Johnson. “They're all dropping like flies just because of the sheer amount of suffering that they witnessed; It’s unparalleled. And so I think they’re still carrying a lot of that.”

Davies, 38, teaches Clinical Pastoral Care Education courses as well, and she says that much of what she teaches her students has to do with learning how to maintain their own emotional wellbeing so that they can care for others. Especially after this past year.

“Even right now, when we're not in a surge, I'm cognizant of my students’ cumulative exhaustion since the pandemic started,” said Davies. “A lot of it is helping them to see and acknowledge and be aware of their own feelings and emotions so that they can honor the emotions in others.”

For Fried, practicing chaplaincy during the pandemic will stay with her for a long time, and she’s learned to recognize when she might not be able to give the care she wishes she could. “I think it just really made me aware of how long lasting the intensity of the pain that we're asked to witness and hold is, and that that can become sort of ingrained in your body and needs to be processed over a longer period of time,” Fried said.

When she got home from her shift the day after the baptism, her husband ordered her favorite takeout dish, Pad Thai, and she spent the afternoon watching The Real Housewives and taking moments to cry. Fleenor and she have a running joke that she’s the crying chaplain.

“Your body needs to release the anguish and the fear and uncertainty,” Fried said. “All that needs to come out, and my way is through crying.”

Is online dating a more permissible option for Muslims?

Is online dating a more permissible option for Muslims?

Ammal Hassan

The Muslim dating app Muzmatch has one of the boldest taglines in the world of online dating: “Muslims don't date – they marry.”

In one breath the statement encompases the views of Musim scholars’ Islamic interpretation of dating: unless it is done the right way, it is haram–forbidden by Islamic law.

With the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic last March, Muzmatch saw a massive surge in use, with a 45% increase in user downloads globally within the week of March 15 to March 22 2020. The app can be argued to have shown young Muslims a more halal–or permitted_way to form romantic connections online rather than in person. However, with cities opening up as COVID infection rates subside and populations receive their vaccines, will young Muslims continue meeting each other online?

That is the question that many Muslims are asking but the answer is not at all clear. It turns out that there are both advantages and disadvantages to the new dating technology. Some say that these apps are certainly more halal because of the way in which they limit physical contact, some say there are still ways to sin through the usage of the app.

Most agree, however, that the apps are certainly convenient. How permissible they are, ultimately all comes down to the intention of users.

Fahmida Rashid is a Long Island native who self describes as a “kind of quirky, weird person.” She believes her personality and unique sense of humor do not come across as well online as they do in person. But the pandemic forced her to limit her social interactions, so she took a chance on meeting a partner through dating apps like Muzmatch.

Now though, she and many others prefer to revert back to dating in person.

“I think I do prefer dating in person – have I done that before, or have experience with that? That's probably a no,” Rashid, 27, said, “[but] like going to the mosque, or like going to events, going for yoga, going to things I like and just trying to meet people that way, so that there's at least a commonality.”

In Islam, modern, Western definitions of dating should not exist. Islamic rules dictate a man and a woman should not be left alone for fear of committing physical sin. In fact, the Prophet Muhammad once said “whenever a man is alone with a woman, Satan is the third among them." Therefore, instead of modern ideas of dating, Islam encourages “dating” as a chaste, focused courtship with the purpose of marriage, which is not just between two people, but also with their families involved.

According to Islamic teachings, that is what should exist, however, despite the rulings, many Muslims have still dated alone, without the involvement of families and not always with the purpose of marriage. Apps like Muzmatch have tried to change this and create a more acceptable way for Muslims to date and marry.

Through the Muzmatch nature of being online, its marriage-focused marketing enables couples to add a third person to their private chat, the app caters to three important islamic rules around dating:

- It must always be done with the purposes of marriage.

- A mahram or chaperone must be present while a man and a woman get to know each other for marriage.

- By being online men and women do not risk the chance of pre-marital sexual relations.

Salams (formerly Minder) is another Muslim dating apps that has halal-friendly features such as a “stealth” mode where a user can pick who sees their profile. Both apps offer the option to have your photos blurred in an effort to guard modesty, a virtue that is highly encouraged in Islam. In effect, these newer Muslim dating apps create an experience more in line with Islamic practices, and Muzmatch founder Shahzad Younas agrees.

“The app is quite unashamedly, for Muslims looking to find a life partner, you know, and it's quite unashamedly not if you're just looking to date or mess around.” said Younas. “We make it quite clear, even when you build up your profile, of what isn't acceptable.”

While the experience may be close to Islam, the reality for many Muslims can be quite different.

“I may be a cynic, but I think it's a little bit naive to think that it makes [dating] more halal because in my experience, it hasn't,” said Rashid.

This is not the case for all Muslims who began using dating apps during the pandemic. Halima Aweis, a Muslim woman from Rochester, whose videos on her experiences using dating apps like Muzmatch and Salams, are popular on Tik Tok amongst many other young Muslims. For Aweis, the pandemic showed her a more halal and convenient way to date, especially with long-distance, which she prefers. Aweis says that she intends to stick to Muslim dating apps even as New York opens up from pandemic restrictions.

“Because of not being able to be around each other in person for long periods of time, the fact that the vast majority of your communication is virtual, whether it's on FaceTime or on the phone, and that you're kind of limited because of proximity because your ‘x thousand’ miles away, you're not given the opportunity to do lots of free mixing and engage in things that like aren't permissible,” she said.

The benefit of these apps, as the six people interviewed for this story have agreed, is that it is certainly a convenient way to meet potential partners. Chastity McFadden, a Muslim woman who both converted to Islam and tried out Muslim dating apps during the pandemic, found that the apps broadened her reach.

“I think what apps could do is help you date outside of your small circle, which tends to be like, one culture, one area, one idea of what Islam is and sometimes that [is hard to do] in your space, so finding people that don't exist in that space might make it actually easier,” said McFadden.

The apps certainly do their best to try to create a halal environment, but at the end of the day, it all ultimately comes down to the intent of users – a point that Younas was sure to make.

Farwah Sheikh, a nutritionist and host of Spill the Chai podcast, which discusses dating as a Muslim, adds onto this by explaining that connecting on dating apps still holds some haram elements as they are based off of physical attraction, but what comes of that is the intention of users.

“You are swiping based off of someone's aesthetic, like right off of their physical appearance, because you're attracted to them to some extent and then the conversation can lead to a place where when you do meet you do want to become physical because you've built up that [attraction],” said Sheikh, “or, it really just eliminates that physical factor [of meeting] and you just get to know someone and then you know you move from there – I think it's the intention of the person, of how they're going in talking to somebody.”

Though some may argue that dating online is still a much more innocent option than dating in-person because of the reduced risk to physically sin, Salwa Ameen a Muslim marriage life coach said that dating digital does not actually reduce the risk of sinning. Conversation on the app may still be inappropriate, including the exchange of elicit photos.

Because of the subjective nature of human intention, despite the apps’ purposes to create a more halal environment for dating, many Muslims, particularly women, have had to deal with inappropriate advances. Because of this they agree with Rashid’s point of view.

Sanjida Rashid, who is the twin-sister to Fahima and has used several Muslim dating apps, spoke about how her own personal experiences with inappropriate behavior on the apps is what makes her prefer prefer dating in person.

“In person I feel that there's still a level of decorum, but online, people feel brave enough to say whatever they want,” Rashid, 27, said. “I had one guy straight up ask me to send nudes and it’s like I just couldn't even believe I was on a Muslim dating app.”

In addition to this, more features like the option for a chaperone or the option to blur a user’s photos do exist to allow a user to make their experience more halal, however, they are optional.

Rashid also expressed that though the feature of a chaperone was not available to her while she was using the Muslim dating apps, she would not have opted for the feature anyway because for her, privacy is necessary from the beginning.

“I don't know who the chaperone would be, whether it would be my parents or my sister, but I just feel that's weird because when you put a third person in the circle, it changes the dynamics of the communication,” she said.

Further, many Muslims believe that dating in person is the way to go simply because it is the best way to truly know the other person.

“I think the apps have this way of hiding who people fully are and you can’t understand even simple things like if your energies mesh well,” said McFadden. “It’s easier to hide the bad stuff about yourself on an app than it is in person.”

As things stand, many Muslims plan to revert back to dating in-person, however, the convenience of the apps has shown to be beneficial. For that reason Ameen believes that even with more people dating in person, dating online is still here to stay.

“I don't think that seeking a partner online will ever really go away,” said Ameen.

High Life: Christians and Cannabis Legalization

High Life: Christians and Cannabis Legalization

Jessica Mundie

When the Rev. James T. Roberson was a defensive tackle for the James Madison University football team he took part in his school’s pro day, when NFL scouts travel to recruit new talent. But, during tryouts, he pulled his hamstring and had to drop out.

“After that I just started reeling,” he said. Roberson turned to cannabis to numb the pain. Before he would go out for dinner with his friends, he would smoke. Before he went to the movies, he would smoke.

“It got to a point where I was doing it every day,” Roberson, 44, said.

Eventually, Roberson, a pastor’s son, began to examine and question the role faith could play in his life. He was skeptical, he said, mostly of Christianity’s racist and patriarchal elements, but as he read the Bible, he started to pray and grow in his newfound faith.

Eventually, Roberson ended up becoming a pastor at a church in North Carolina. Now he runs Bridge Church NYC in Park Slope, Brooklyn, which he has branded as a “a church for people who don’t go to church.”

Roberson is using his platform as a church leader to talk about the legalization of marijuana and other important cultural issues that are not usually discussed in faith spaces. He does not use marijuana anymore or encourage others to partake, but he, and an increasing number of Black church leaders, see efforts to legalize the controlled substance as a path to religious redemption for Black Americans.

Earlier this year, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the New York State Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, which legalized recreational use of cannabis for people over 21 and made New York the sixteenth state to permit the possession of the controlled substance. The law also allows for those who have been convicted of marijuana related convictions to have their records expunged.

Amid the legalization discussion, Roberson is one of many pastors reconsidering their message about marijuana. Of course, pastors don't want to push a controlled substance from the pulpit, but they see opportunities for economic development in hurting communities, a remedy to historic injustices and a new way to reach lost souls.

For Black religious leaders like Roberson, legalization is an important stepping stone in the fight for racial justice. A report by the American Civil Liberties Union found that in 2018, even though white and Black Americans consumed marijuana at the same rate, Black people were almost four times more likely than white people to be arrested for possession. That disproportionate ratio has not changed even as the overall number of arrests for possession has gone down in the last decade.

“From a legal standpoint, this is a good thing for the Black and brown communities to no longer have this as one of the primary reasons we see Black men disappear into prison,” said Roberson.

His position contradicts how most American clergy feel.

According to a LifeWay Research poll, the majority of Protestant pastors say getting high is morally wrong. Since before legalization, mainstream Christian denominations have had differing opinions on cannabis legislation.

Certain denominations approve the use of medical marijuana, like the Episcopal Church, Presbyterian Church, and United Methodist Church. The Roman Catholic Church considers drug use an offense if it is not used “on strictly therapeutic grounds.” Other religious organizations, like Concerned Women for America, an evangelical Christian group, and Focus on the Family, a conservative Christian ministry, oppose legalization under any circumstances.

Roberson is not the only church leader in New York City considering the importance of social justice and equity in legalization. The Rev. Anthony L. Trufant, senior Pastor of Emmanuel Baptist Church in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, said he sees the legalization of recreational cannabis as an opportunity for his community to thrive.

In February 2021, the Baptist megachurch held its second annual cannabis summit. The two-day Business of Cannabis Summit discussed how Black and Latinx communities can benefit from the growing cannabis industry through business opportunities while also addressing issues of social justice and reinvesting in communities.

This year’s summit participants heard from Niambe McIntosh, whose father Peter Tosh played guitar with Bob Marley. Tosh was severely beaten by police after lighting a joint and advocating on stage for legalization. She spoke about her brother who was arrested and served time for cannabis possession. While the summit was remote this year due to the coronavirus pandemic, it still attracted over 2,000 guests, Trufant said.

The summit is a partnership between the church and Women Grow, an organization that hopes to connect, educate, empower, and inspire the next generation of cannabis leaders, said Gia Moron, President of Women Grow. Trufant said their partnership was formed based on their shared understanding of what the possibilities of legalization meant for communities of color, the Black community in particular. They see it as an opportunity for economic justice.

“Pastor Trufant had the foresight to understand that this was information that needed to be shared with his congregation and with the greater community,” said Moron, who is now a member of Emmanuel Baptist Church.

While the summit was an opportunity to address issues of social justice, Trufant also wanted it to be an opportunity for members of his community to learn about how they can benefit from the growing cannabis industry. There were sessions about career and business opportunities involving cannabis and real estate, CBD products, investing, and health and wellness.

According to the Rev. Alexander Sharp, founder of Clergy for a New Drug Policy, the church is an important place for conversations to start around cannabis policy, and the bigger issue of drug addiction.

“Churches are shamefully silent,” said Sharp.

He explained that they should be used as places for education and debate about drug policy. Hopefully, he added, if a church is seen as welcoming, those who suffer from addiction or want to change their dependent relationship with marijuana, will find a welcoming and nonjudgmental community within a congregation that could help them change.

Founded in 2015, Clergy for a New Drug Policy aims to bring clergy across different faiths together to join the fight to end the war on drugs by promoting education, safety, and treatment. Sharp, an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, started the organization because of his background in theology and public policy. Sharp’s overarching goal is to mobilize religious leaders to think of drug use as a health issue and not a criminal one.

Sharp offers several different reasons why religious organizations should advocate for drug policy reform. He writes that at the center of Christian faith “is a loving God of mercy and forgiveness, seeking always to heal and yearning for us to be united as brothers and sisters in God’s love.”

To him, the war on drugs does not meet these criteria. Through Clergy for a New Drug Policy, Sharp supports policies that aim to decriminalize all drugs and shift the culture of punishment to one centered on public health solutions.

In terms of marijuana prohibition, Sharp argues that it “stigmatizes people; it brands and marginalizes them. It stands in opposition to God’s love, healing, and forgiveness.”

Not only does legalization help correct historic injustices against minority communities, but Sharp says it is a distinctly religious stance – one of forgiveness and compassion.

Before Emmanuel Baptist Church’s first summit in 2019, Moron said there was some hesitancy within the congregation. She said some members thought it meant people would be consuming and selling cannabis on the property. But after congregation members heard keynote speakers and attended discussions with political leaders, doctors, nurses, entrepreneurs, and advocates, the majority of them Black people, they changed their tone, she said.

Trufant said even though some members of his 4,000-person congregation were skeptical of the summit, the church was proud to address an issue that is pertinent to its community.

“Emmanuel Baptist Church has always been unafraid to step into the public square, and address issues that others might find to be taboo,” said Trufant.

While the Business of Cannabis Summit at Emmanuel Baptist Church was an opportunity for congregation and community members to gather and discuss social justice issues and business opportunities, it was not meant to open discussion on the moral or religious reaction to legalization.

Roberson said he is hesitant to say Christians should start consuming cannabis. While the Bible does not explicitly forbid the use of cannabis, Roberson said, it does offer a framework for avoiding intoxication as it relates to alcohol and entering states of mind that would alter your relationship with God.

In the Bible, the use of alcohol is celebrated, explained Roberson. The Lord’s communion and Jesus’s first miracle, turning water into wine, are indications of how Christians should consider alcohol use in their lives.

“The principle is everything being done in moderation,” he said. But he admits he’s not 100% positive that the same rule applies to marijuana. “Now, can you smoke weed in moderation? I don’t know.”

Todd Miles, a theology professor at the evangelical Western Seminary in Portland, Oregon suggests other areas of ethical concern when considering cannabis use in his book Cannabis and the Christian. Christians are not to be mastered by anything other than God, he writes. Cannabis also can dampen a Christian’s dedication to discipleship and stewardship as well as their responsibility to their faith, he said.

Miles and Roberson share similar views on the religious use of cannabis. “I do think that the case can be made that the biblical prohibitions on alcohol intoxication apply to marijuana intoxication,” said Miles.

He also believes that while the Bible may not have the answer to every potential ethical question answered explicitly, it does offer all the divine words that a Christian needs to live faithfully before God. The framework he offers for ethical decision-making on cannabis consumption in his book takes biblical wisdom and discipleship into consideration.

Some of the questions he asks Christians to consider are: is there any reason to smoke pot recreationally other than to get high? Can you be sober-minded while you're using marijuana? Will THC, the main psychoactive compound in cannabis, diminish my ability to live a life that honors Christ?

The legalization of cannabis will continue to be a nuanced issue for Christians, said Miles. While the legislation will be beneficial for communities of color and offer economic opportunities for those historically affected by prohibition, Christians need to consider if this substance will bring them closer to God. Roberson offers an answer to the question, should Christians consume marijuana. He concluded that without moderation, weed becomes a master.

“We want the spirit life to be our life,” said Roberson. “Not the blunted life, not the stoned life, not the high life, not the baked life. If a Christian tells you it's cool to get high all the time, they’re wrong.”

An organist for the king

An organist for the king

Pablo Argüelles Cattori

On a Sunday in early July, 10 minutes before the 10 a.m. mass, a murmur fills the Church of St. Paul the Apostle, a Roman Catholic parish in midtown Manhattan. It is not the distant sound of rain; It’s sunny outside. It’s not the whispers of the parishioners, as the pews have not yet been filled. It’s the murmur of a pipe organ’s blower.

Hidden below the main altar, it is a gigantic machine, more suited to a steamship than a church’s basement, and it’s pumped a steady amount of pressurized air into the lungs of the towering instrument standing still on the apse.

The murmur announces music to come, and signals that Dan Ficarri, a young, thin man wearing an ocean-blue shirt and dark-grey pants, is about to sit down at the organ’s console and play for Mass. When he does, the nave fills with music, and the organ begins to breathe.

Ficarri, 25, has been an organist since he was a boy. While other kids his age were playing ball in middle school, he was already playing music at funerals and weddings. He quickly learned to accompany the happiest and saddest moments of people’s lives.

“Playing music at church is different from making music in a concert hall or outside in an amphitheater,” he said. “There’s a certain solemnity and spiritual quality to it.”

Ficarri is quick to acknowledge that his profession can sometimes be seen as obscure. He's had to defend it, even from classical musicians who think that pipe organs are nothing more than old instruments to play slow hymns in half-empty churches.

Ficarri knows better. Organ music is alive and thriving. Later this month, he will become the next Associate Organist at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the seat of New York’s Episcopal church in Morningside Heights.

Beyond denominations, Ficarri has faith in organ music.

Mozart called the pipe organ the king of instruments. Pipe organs are, in a way, omnipotent. They are capable of producing the softest and loudest of sounds, and the highest and lowest of pitches. Its pipes can be as large as trucks and as small as pencils. They can produce voices that mirror the world –there are even pipes meant to imitate a human singer’s voice. If needed, they can replace a full orchestra.

They are also kings in an atavistic sense. Up until the Industrial Revolution they were among the most complex machines ever built. They’ve also been around for a while, since Hellenistic times, well before the birth of Christ. Thanks to the powerful sounds they produce, pipe organs have been used in arenas, fairs, and theater halls, and it was not until fairly recently –five centuries, more or less– that pipe organs slowly found their ways into churches.

And a Catholic church in Franklin Park, a suburb north of Pittsburgh is where Ficarri expressed his talent for music. He played the violin there every Sunday and started playing the church’s digital organ around middle school. It was a tough place to learn the obscure art of organ playing, so he relied on his own work and instinct. He listened to recordings and watched people play on YouTube. It was a more n instructive than inspiring period.

Then, when he was 15 years old, Ficarri had an epiphany. Paul Jacobs, a Grammy Award-winning organist and Chair of Juilliard's organ department, performed at Pittsburgh’s Heinz Memorial Chapel. It was a French Romantic program, with pieces by Louis Vierne and Maurice Duruflé. Ficarri listened in awe. “I had a realization of what the organ could do.”

He found Jacobs’ email and contacted him. Jacobs, an organ apostle of sorts, offered to give Ficarri a lesson. In 2014, two years after he discovered the organ, Ficarri became a student at Juilliard, with a partial scholarship. He arrived at a small department, with only a dozen students, most of whom were already finishing their master’s degrees or getting their doctorates.

Ficarri was taken aback by the bright lights, big buildings and diversity of New York City. But the city also captivated Ficarri in a more personal sense. It is one of the most densely populated cities in the world when it comes to pipe organs. According to the American Guild of Organists’ New York City chapter, there are pipe organs in at least 100 Christian and Jewish houses of worship across the five boroughs, from the Armenian Church of America and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Manhattan to Greek Orthodox churches in Queens and Moravian congregations in The Bronx.

The list is an impressive, multifaceted testament to the religious history of the city, born of waves of immigrants bringing their lives and faiths. A wealth of treasures, most of them hidden, was waiting for Ficarri to find them.

“One of the things that organists often do whenever they're in a new place is to go around and see and hear all of the different pipe organs,” he said. He found his favorite instruments at St. Mary the Virgin, a Catholic parish near Times Square, at St. Ignatius Loyola, another Catholic parish on the Upper East Side and at St. John the Divine.

Meanwhile, he found his first job as an organist at Hitchcock Presbyterian Church in suburban Scarsdale. His tenure there prepared him for his arrival to St Paul the Apostle in 2015.

Ficarri knows St. Paul the Apostle better than any other church in the city. It’s located on Columbus Avenue, two blocks away from Juilliard and Lincoln Center, and it was one of the first Catholic churches to welcome him as a gay man.

The church of St. Paul the Apostle, built in 1859, is administered by the Paulist Fathers, the first men’s religious order established in the United States, now known for its progressive stances. He plays for its parish regularly, when he’s not studying his craft.

The instrument at St. Paul is not old in comparison to other organs in the city, but a 1964 Möller with a four-keyboard console, plus the pedals. It’s a workhorse that, blowing, puffing and huffing, gets the musical job done. But Ficarri knows that it can falter at any moment. Parts of the organ have been held together by duct tape for years.

To the untrained ear, though, the organ sounds superb in the hands of Ficarri. Five minutes before a Mass begins, Ficarri sits down at the Möller’s console.

He starts with a prelude and an opening hymn. Then, following the reading of scriptures, he accompanies the congregation for the Kyrie, the Gloria, the responsorial psalm, and the Alleluia, which preceded the reading of the Gospel. After the homily, he plays the offertory hymn, the Sanctus and the Agnus Dei. He finishes with the postlude. The music fills the whole ceremony. And in turn, Ficcari wraps his entire mind and body around the music.

“You're always thinking about how you're operating the instrument mechanically, how you're executing the music, technically, with your fingers and with your feet,” he said. “Then, of course, you're thinking abstractly, musically, with your mind. And the brain obviously controls all of those things. Different parts of the body are always doing different tasks.”

Performing for mass is only a small portion of Ficarri’s duties as an organist. He also conducts the choir, planned weddings and funerals, and organized concerts.

Ficarri plays, but he also listens: both to the capricious Möller organ –which needs constant care and calibration– and to his fellow musicians, as well as to the church’s parishioners.

“He’s incredibly easy to work with,” said Luisa Torres, a soprano and former cantor at St. Paul. She now sings for the Archdiocese of Newark. “He anticipates where I’m going, and I know where he’s going.”

For a recent funeral at St. Paul the Apostle, he sat down with the family members of the deceased. He talked to them about the different options of music he could play, and then they shared with him the music that was special to the deceased. “I worked with them on planning something that was meaningful to them,” he said.

In the last week of July, shortly before finishing his tenure at St. Paul, Ficarri got a call from Kent Tritle, the Director of Cathedral Music and Organist at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, in uptown Manhattan. He wanted Ficarri to audition for associate organist. He got the job.

“I'm still in disbelief,” he said. “It's as wonderful an opportunity as I could have ever imagined.” He will start his tenure on August 20.

According to Paul Jacobs, Ficarri's former teacher at Juilliard, to be appointed Associate Organist at St. John the DIvine is an honor. The Episcopal church is a New York City landmark and one of the most famous cathedrals in the world.

“Involvement in such a robust, visible music program will require extraordinary musical and personal skills,” said Jacobs. “Fortunately, Dan possesses them."

Juilliard organ students hold the strongest record for job placement immediately upon graduation. Some of them go to teach at college level, and others are appointed to posts at houses of worship in the United States and abroad. One year after graduating from Juilliard, Ficarri got one of the best positions available.

While happy for the opportunity brought by St. John, Ficarri has never been overly worried about the prospects of finding a new job.

"Obviously, everybody has certain worries and anxieties," he said. "But the perk to being an artist is that when you're in doubt, you just create."

Indeed, Ficarri decided to leave St. Paul to bring balance to a prolific and versatile career. He performs regularly, his work is published by Morning Star and E.C. Schirmer, and he self- publishes through Sheet Music Plus, an online retailer of sheet music.

He also writes organ pieces on commission for churches of all denominations.

"I try to make music that is inviting and not something that's just for an exclusive group or only speaks to people of a certain kind or a certain background or religion."

As a church organist, he knows that the music he plays is universal.

“It creates incredible vibrations in the building,” he said. “And whether you're conscious of it or not, you're always surrounded by it, and can feel to a certain extent those vibrations. There's a mystical quality to the organ because it can be incredibly loud. For a long time in history it was one of the loudest sounds that anyone ever heard. And while it's being played, outside of the keys moving, the pipes are just standing still.”

And perhaps that’s why, after the mass had ended last month and people had left the building, Ficarri kept playing the old, puffing Möller organ. After all, for him, playing is a matter of faith.