For Catholics, Sometimes the Body Is a Prayer

Countless embellishments compete for the visitor’s attention as she steps into the Church of St. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit house of worship in the Flatiron District of Manhattan. The décor is so distracting that she may miss her cue to stand in prayer or kneel in submission.

The early morning sunlight turns blue as it shines through stained glass windows, which have the color-scheme of a peacock. For every detailed oil painting of a saint, there is a corresponding warm glow emitting from lanterns or candles. The building is drenched in ornate, pious eye candy. However, the culmination of the basilica is the sizable, golden Gospel Book, resting on a slanted stand at the front of the church.

Behind the stand is the Rev. Ricardo da Silva, St. Xavier’s associate pastor, who recited the Lord’s Prayer with his arms stretched out and his palms facing the rotundas. This position is the “orans position,” which comes from the Latin word meaning pray. This position during Mass is symbolic of leadership in prayer. It is called for the priest alone during the Our Father prayer, with the elbows close to the sides of the body and with the hands outstretched sideways, palms up. The orans position exemplifies Catholic deference of the church hierarchy and the Church’s belief that the body is a necessary mechanism of communication for the spirit.

As the priest, da Silva is a representative of God, who utilized this body position to invite the Holy Spirit into the Church. The priest’s fingers, facing the heavens, are a privileged symbol of a leader’s power in prayer and praise.

Biblically, this position is a sign of surrender. An example of the orans position is in Exodus 17:11, which stated, “as long as Moses held up his hands, the Israelites were winning, but whenever he lowered his hands, the Amalekites were winning." Completely submitting to God by lifting the hands benefitted Moses, allowing the Hebrew prophet to protect and led his people.

During the prayer, a nearby mother swatted her seven-year-old’s little hands down, which were previously outstretched with palms up, mimicking Father Ricardo. The mother’s scold can be translated to mean that the orans position of prayer is reserved for the office of the priest. Justification for making this position exclusive lies in the Church’s liturgical documents, Instruction On Certain Questions Regarding the Collaboration of the Non-Ordained Faithful in the Sacred Ministry of Priests.

"In eucharistic celebrations, neither may deacons or non-ordained members of the faithful use gestures or actions which are proper to the same priest celebrant,” stated the Vatican in 1997. “It is a grave abuse for any member of the non-ordained faithful to ‘quasi preside’ at the Mass while leaving only that minimal participation to the priest which is necessary to secure validity.”

The child’s confusion was understandable. Not following the priest’s moves is an exception to customs. A general rule of thumb for an unconfirmed or unfamiliar person at a mass service is to imitate the posture of those around her. When others stand to pray, she rises to her feet. Standing in Catholicism is considered the appropriate position for prayer and is also a way to show awe to Jesus, who is represented by the priest during Mass. When the celebrant instructs the laity to sit, she takes the weight off her feet. When the laity kneels, she shifts to her knees. When worshippers genuflect, they submit to their Heavenly Father. The priest is a representative of Jesus, he leads the congregation to do gestures and rituals that are part of the Catholic Mass Order.

With all of that moving around, the role of the corporal body in the church’s body was paramount. But changing postures was not simply posturing. The physical positions symbolized believers’ spiritual pleadings - all in unison. The worshippers did so (or, in the case of the orans position, did not do so), to respect the church hierarchy, and in turn, God.

Even in the progressive doctrines of St. Francis Xavier, which is an inclusive church that regularly advocates for racial justice and LGBTQIA rights, da Silva still found use for principles of posture and ritual.

“A new perspective can reveal the sanctity of tradition,” he said.

A Sunday Langar Brings Together Sikhs in Queens

Midday on a recent Sunday, The Sikh Cultural Society in Richmond Hill, Queens, is packed with the faithful. They come to pray, to socialize and to eat in a religious ceremony called langar—the communal meal shared after the prayers.

Everyone in the gurdwara is barefoot and wears a head covering. As worshipers enter the main service room, known as the Darbar Sahib, a man in a white linen gown scoops up a healthy portion of a sacred treat called parshad and places it in my bare, cupped hands. I rise and make my way to the opposite side of the room. Women on the left. Men on the right.

This separation, I am told, is done at some gurdwaras out of respect, to avoid distraction and to allow worshipers to feel comfortable, should their shirts rise when kneeling to pray or if they need to breastfeed a child. “It’s a completely cultural practice,” one worshiper, Tandeep Kaur, told me in a phone conversation. “It doesn’t have any religious background.”

After exiting the room of worship, I go down the stairs with other worshipers for the langar.

I grab a metal tray that comes complete with a metal bowl, metal spoon and napkin. This begins my experience with langar. The basement of the gurdwara serves as a community kitchen where volunteers cook the multiple meals and wash the hundreds of dishes. The Sikh house of worship and its kitchen are open continuously to anyone regardless of their faith.

I am directed by an elder volunteer to a spot on a burgundy runner rug.

Clink!

That is the sound the metal tray makes on the floor before me. My feet and legs then fold into the sukhasana position. In the Sikh faith, everyone sits on the floor, regardless of their identification, to show that all are equal. The practice has its origins in deconstructing the idea of the caste system.

In the gigantic basement, a few single wooden benches and tables are around for those who can not physically descend to the ground. I sit in between a middle-aged man and woman who are unrelated. The wall in front of me is decorated with framed images of the gurus. My eyes track a little further where I spot a television broadcasting the prayers in the Darbar Sahib to those of us in the eating area.

In the gigantic basement, a few single wooden benches and tables are around for those who can not physically descend to the ground. I sit in between a middle-aged man and woman who are unrelated. The wall in front of me is decorated with framed images of the gurus. My eyes track a little further where I spot a television broadcasting the prayers in the Darbar Sahib to those of us in the eating area.

The lentil soup’s overpowering spices of cumin and cloves linger in my mouth. This is the dhal. Covering my plate is a sweet-tasting cheese and green pea curry called matar paneer, salad, peas pulao (lentil rice) and a dessert of rice pudding, called kheer. The pani, or water, sits in a metal bowl from the set awaiting consumption from the diners.

As we eat, the barefooted men make the rounds again with their vats of water, dhal, kheer, rice, parathas and salad asking those sitting if they would like additional servings.

After the meal, I get up and grab some hot chai (tea). I pace, unaware of where to stand or sit when a male volunteer gestures to me to have a seat at the end of yet another sliver of carpet. I thank him and seat myself at the far end of the reddish rug I have now grown accustomed to. I am in a row of men also sipping their chai and chatting or quietly contemplating. Around me are the voices of young children running around discussing their allowance, grades and what latest sneaker their good grades will allow their parents to buy for them.

In my stocking feet, I make my way up the stairs and through the long corridor before sharply turning right to retrieve my clothes. I get dressed and walk the pavements of Richmond Hill before stopping to visit the sign: Punjab Avenue.

Small acts of kindness

On Thanksgiving Day of 2020, eight months into the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, Susanne Walther, a palliative care nurse working in New Jersey, received a text message from the wife of a former patient who died in the early days of the pandemic. The wife said that she thought about Walther, 61, often and that she would never forget her.

The message was a reminder for Walther that “small acts of kindness stay with people forever.

”What had she done? She simply “didn’t let them throw away her husband’s belongings,” she recalled. “Even when people are acutely grieving the loss of someone they love, they still have the kindness in their hearts to reach out to the clinicians who have cared for them.”

As the director of the palliative care team at University Hospital, a 519-bed hospital in Newark, New Jersey, Walther works closely with patients close to death. This means that she often talks with families when her patients are near the end of their lives, which would sometimes wear on her mental health.

The year of the pandemic has taken a toll on health care staff. Many frontline workers have left their jobs because of the pressures. Those who continue this work, like Walther, report that they are sustained, in part, by the thanks and appreciation they get from patients and their families.

The message meant so much to Walther. It reminded her that while they could not always save those suffering from COVID, they could offer comfort to them and their families.

In the early days of the pandemic, nurses and other frontline workers were especially important because few visitors were allowed in hospitals. Family members dropped their loved ones at the door of the emergency room and might never see him or her again.

The wife who texted that she would never forget Walther was one of them. Her husband was sick at home last spring and did not come to the hospital until the last minute. The staff attempted resuscitation with CPR, breathing machines and life support, but he still died in less than an hour at the emergency room. Right before the staff took his body out of the emergency room, Walther noticed his bag of personal belongings underneath the stretcher, which would get thrown away soon.

During the pandemic family members often called the hospital about clothes, wallets or watches that belonged to deceased patients, but the items were already gone, Walther said.

“It was such a panic with COVID. People were so scared that sometimes the belongings would be thrown in the garbage,” Walther explained. “Nobody wanted to touch them. People thought if they opened up the bag, they would get infected.”

Walther did not want this to happen to the wife of this patient, so she took the man’s belongings and planned to return it to his wife.

A month later, the wife and Walther met outside of the hospital. She handed Walther the small tropical plant inside her husband’s bag of belongings and insisted on Walther keeping it.

She told Walther, “Your kindness was the only thing that pulled me through my husband’s death. I cannot thank you enough.”

Since then, Walther has been watering it once a week, and the plant is thriving in her office at the hospital.

Born in 1959, Walther graduated from Rutgers University in 1985 with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and started working as a nurse in New Brunswick. To search for more challenging work, she quickly transitioned into the intensive care unit and worked as an ICU nurse for nearly 20 years.

From 1987 to 1990, Walther worked as an agency nurse in Bergen County, NJ. As an agency nurse, she got staffed in ICUs and critical care areas of different hospitals over the county based on needs. In 1990, Walther joined University Hospital.

Working night shifts from 7pm to 7am, she rotated all around different units in intensive care units, including the medical unit, the surgical unit, the trauma unit, and the neurological unit.

Patricia Murphy served as the director of the palliative care team at University Hospital until her retirement in 2013. She said that Walther is “one of the most specialties you will ever meet when it comes to caring for patients… families would tell me about this wonderful nurse who took such good care of the person they loved.”

After working in ICUs for 17 years, Walther burned out: “I found myself working very, very hard to keep people alive at all, you know, even though it appeared as if they were not going to survive.”

“I was just overwhelmingly morally distressed by some of the work that we were doing on people’s bodies. And I felt a great need to be sitting with families and talking to them instead of taking care of the patients,” Walther explained.

Around that time, Walther was thinking about graduate school programs, and Murphy suggested palliative care. In Murphy’s opinion, Walther already had all the skills needed to be an ICU nurse, but the skill she was missing was how to be with families in times of crisis.

In the following three years, Walther continued to work night shifts, split the duty of raising two children with her husband, and received her master’s degree in palliative care from New York University in 2005. Shortly after her graduation, Murphy hired Walther to join her team full-time at University Hospital as an advanced practice registered nurse.

“It was extremely morally and professionally satisfying to be moving into palliative care, and setting myself up to work with families, having meaningful conversations, and empowering them to have options and choices and making decisions about their loved ones,” Walther said.

Recently, Walther worked with a young woman in her late 20s, both of whose parents were critically ill after contracting COVID. Her father, only in his 50s, was on a ventilator at the hospital, while her mother was also on a ventilator at another hospital.

Having conversations with family members on the end-of-life of their loved ones can be tough, but Walther never shies away from those conversations. She felt obligated to inform the daughter that some families would find this type of prolonged life support unacceptable and wanted their loved ones to die peacefully, liberating them from the machines and the tubes.

Later that day, the mother of this young woman died at the other hospital. The daughter called the hospital and said that she wanted her father taken off life support and any treatments to be discontinued. As the medical note suggests, the daughter wished his father to have a natural death and be at peace with his wife who had just passed.

Walther still choked up when talking about this case. “I really didn’t want to call her and have this conversation because I knew it was going to be a very hard conversation,” Walther said. “And yet, I feel like if I never told her this and never gave her this opportunity, she never would have been empowered to consider that she could actually let her parents die on the same day and be together wherever she thinks they are, after they die.”

Although Walther has many intimate conversations with patients and their family members, she does not keep in touch with them afterward the service. However, working in a small community where many people have limited health care resources, Walther has helped multiple families through multiple losses.

After Murphy retired in 2013, Walther became the new director of the palliative care team at University Hospital. Currently, the palliative care team has four people, including two advanced practice registered nurses, one social worker, and one licensed counselor.

When COVID first hit New York City last year, tens of thousands of people died. The operating rooms at the hospital were closed, and most of the staff got relocated. Despite relocations, the palliative care team supports not only patients and families but also their colleagues at the hospital.

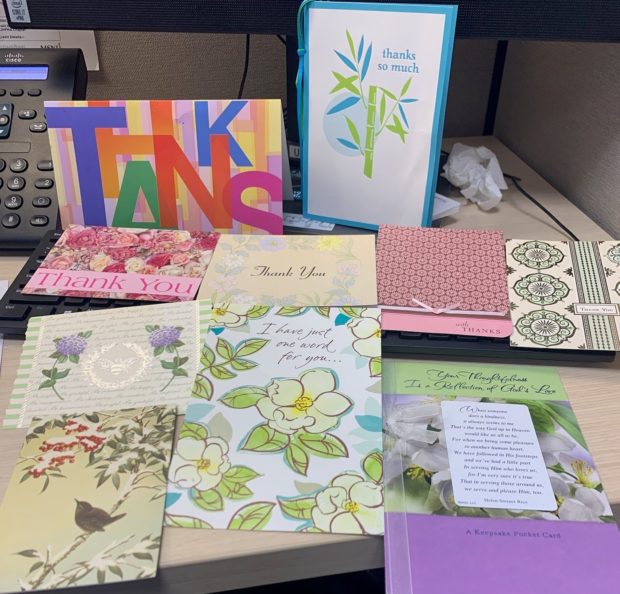

“One of the things our team was talking about, through the surge last year, was how little we felt that we could actually do for people,” Walther said. “But we have so many more thank you cards from families showing such appreciation for the smallest, tiniest way that we helped them connect with their loved ones.”

Christianity and natural farming in the Hudson Valley

Christianity and natural farming in the Hudson Valley

Sara Badilini

A tall wooden cross and an American flag announce the entrance to “Freedom Hill Farm,” in Otisville, a rural village in Orange County, N.Y, that is north of the city, but not quite upstate.

The owners of this 50-acres , Rick Vreeland and his wife Julie Vreeland, are born again Christians. By combining the principles of natural farming with those of Christianity, they hope to fulfill their mission of sharing the Gospel with others.

“We don’t own the farm, we simply take care of it,” said Rick Vreeland, 67. “It belongs to God.”

The cows and their calves mooing in the barn are the soundtrack of this holy land, which is dotted with colorful signs singing God’s praises.

Jewish, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and even atheists visit the farm frequently as well however, shopping their products and asking questions about the owners’ faith.

From the cows’ milk, the Vreelands produce yogurt, buttermilk, and kefir that they sell and distribute in retail locations from Albany to Brooklyn.

All of the employees — two full-time, five part-time — and the several volunteers are Christians. “We don’t ask for it, but God seems to send us only other Christians,” Julie Vreeland, 64, said.

Faith hasn’t always been so central to the Vreelands.

Julie Vreeland grew up in Otisville in a Roman Catholic family, but she “unconsciously fell away from religion,” right after receiving the sacrament of confirmation, at the age of 13.

Rick Vreeland never stepped into a church until he turned 38. “Everything changed that year. I was crossing a yard and I heard a voice telling me ‘You have to go to church,’” he said.

He doesn’t know why God picked that particular moment of his life to speak to him, but ever since, he has dedicated his life to what that voice called him to do.

After growing up on the family farm, not far away from where Freedom Hill Farm is today, he started farming in 1972, when he opened his own commercial farm with a colleague. His wife joined him in 1975, after they got married. Together they worked on their commercial farm for 26 years with more than 2,000 cows.

Despite the success of their business, they decided to quit and four years later they opened Freedom Hill Farm. The barn had been a property of the Vreeland family since the 1930s. After farming it for generations, the dairy farm shut down in the 1960s, and the barn sat empty until May 2007, when the Vreelands opened Freedom Hill and nine milking cows started calling the barn home.

“Before renovating the place we had been praying for years,” JulieVreeland said. “I wanted to do something for Jesus, but didn’t know what.”

Then they came up with the idea of a small dairy farm that could also be a Christian ministry for the youth.

The Vreelands understood they made the right choice when they met their neighbors, who run the Freedom Farm Community, a nonprofit that also happens to be a Christian ministry for young people in the form of an organic farm, where they grow tomatoes, cilantro, pumpkins and all sorts of vegetables.

Edgar Hayes, the nonprofit’s executive director, remembers when the Vreelands knocked on the door and announced the plan for their land. The Vreelands and Freedom Farm Community still cooperate today.

“We have our own program for the youths and they’re really busy with the dairy farm, but their cows come on our land, and we share a mission,” he said.

Lou Enoff, president of the Christian Farmers Outreach — a program based in Maryland that supports Christian farmers around the world with different initiatives — explains the connection between farming and Christianity using the parable of the sower explained in Matthew’s gospel.

“To sow the seeds of the gospel you talk to people to tell them about Christ,” Enoff, 78, said.

Christian farming became a popular concept in the United States in the 1980s. To respect God’s creation, devoted farmers started promoting organic agriculture and unprocessed foods, as opposed to more industrialized products, Enoff said.

Some Christian farmers gathered in organizations such as Christian Farmers Outreach, and the Christian Farmers fellowship. Others, like the Vreelands, carry out their Christian mission on their own.

“Once the seed is planted, if it falls on good ground, it grows and produces crops,” Enoff said. “If it falls in the weeds, then the weeds can choke it out. It's similar to evangelism.”

Today, the Vreelands own 36 milking cows and have around 1,000 clients, who come to the farm once or twice a week to collect their order or raw milk. Freedom Hill is one of only a few farms that sells raw, unpasteurized milk and products. They believe that producing whole foods, while respecting their animals and caring for the land is what makes their farming Christian.

The days at Freedom Hill Farm start early. Julie wakes up at 3.30 a.m., checking the milk orders, while her husband starts the day at 4 a.m. Once they are both awake, they study the Bible for about an hour before heading out into the fields.

“We pray for the cows, the land, the people we know. And we pray every day for divine meetings here at the farm,” said Rick Vreeland.

By 5 a.m. he is milking the cows, while his wife feeds the goats. The rest of the farm soon comes to life. The couple’s son shows up to gather the products and deliver them to the retail locations, and the store manager arrives to open the shop. Other employees and volunteers work in the barn, others fill the milk, and one makes the yogurt — which includes the pasteurization process, the culture of the yogurt with bacteria, and a 10-hour setting.

In the early afternoon Julie Vreeland takes the calves from the barn into the adjacent meadow, followed by some young visitors. Each child leads their own calf with a rope, teaching the calves how to follow instructions. One of them struggles more than others when a stubborn calf refuses to follow the young girl’s lead.

When bigger groups of young visitors come the Vreelands organize afternoon activities and games to entertain them, always starting with a prayer. But the rest of the time with the children is dedicated to games and activities, it’s not meant to be a religion class, explains Julie. Vreeland.

“We don’t want to overwhelm the children with a lesson on faith, we want them to witness our faith through natural farming. But when the subject of religion comes up we are happy to speak about it,” she said.

The Vreelands say they have found a way to combine the farmers’ lifestyle with the Christian ministry, but they don’t belong to any particular branch of Christianity. After trying a number of churches and denominations, they’ve found their own way to worship and praise God.

They hold weekly Bible study gatherings at their home — now on hold because of the pandemic. They also pour their faith and Christian values into how they care for the cows.

As they explain, one of the basic needs for cows to thrive is comfort. That’s why the cows at Freedom Hill Farm stay in the barn only while they’re getting milked and they spend the rest of their day in the fields, where they can take a dip in the pond and lay down.

That heavenly environment for the livestock prolongs their life expectancy, Rick Vreeland explains. On average, the cows at Freedom Hill live around 10 years, he says as he caresses the back of a cow whose box is in front of a poster of “The Last Supper” by Da Vinci, hanging on the barn’s wall.

“You cannot just go to church and think you’re going straight to heaven,” Rick Vreeland said. “You have to be born twice and then you secure yourself a place in heaven. This, instead, is cow’s heaven.”

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Kathleen Shriver

Some of the best views of New York’s Statue of Liberty are from a waterside park in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood. From there, visitors can see the broken shackles at Lady Liberty’s feet, the golden fire raging from her copper torch, and the words to “The New Colossus,” the sonnet at her pedestal.

Just a few blocks from New York’s Statue of Liberty, a nonprofit restaurant and school labors to keep the spirit of Lady Liberty alive. It is known as Emma’s Torch, a tribute to Emma Lazarus, the Jewish American poet whose verse -- “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe” – decorates Liberty’s pedestal. Founded by Kerry Brodie, Emma’s Torch aims to empower refugees, asylum seekers, and survivors of human trafficking through culinary education.

When launching the nonprofit, 27 year old Brodie, thought back to her highschool -- Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School -- where she learned about Jewish leaders. She says Lazarus was one of the “unsung female heroes of Jewish history” whose work always stuck with her.

“I felt like Emma never got to see what her poem would become,” Brodie said. “ So my hope is that Emma's Torch will also be able to create that sort of lasting legacy and those ripple effects of change as well.”

In the Jewish tradition, when speaking of a righteous deceased person, many will say Z"l (pronounced zal), which is an abbreviation for Zikronam L'bracha. This literally means “may their memory be for a blessing.” “I think this definitely applies to how we are trying to honor Emma's legacy and memory. We are working in her memory,” Brodie says.

While for many restaurants, reopening after the pandemic means staffing up, adding tables, expanding menus, opening the doors earlier and closing them later, for Brodie, it means reprioritizing. It means reconsidering the purpose of Emma’s Torch and drawing from her past and, as it turns out, her faith.

Since its founding in 2017, Emma’s Torch has become a beacon of hope for hundreds. The nonprofit offers a full-time paid training program, during which students receive instruction, mentorship, and work experience, while also developing English conversation skills and other “soft skills” such as resume development and computer literacy.

In 2020, Brodie was looking forward to formalizing and publishing her curriculum and opening new locations around the country.

“2020 was supposed to be the year of stability,” she said. Instead, she got a global pandemic, an economic crisis, and a racial reckoning.

While the pandemic threatened the lives and livelihoods of everyone, the toll it took on those working in the restaurant industry was especially dire. To make matters even worse, Emma’s Torch doubled as a training program for immigrant communities, some of the country’s most vulnerable. Even so, Brodie had faith.

Brodie’s Jewish faith has gotten her family through a profoundly difficult past. “My great grandparents are among the only people from their families, to survive the Holocaust,” she said.

She recalled that several years ago she joined her grandfather on a trip to Lithuania, where many members of his family were murdered by the Nazis. “Standing there was just such an eye-opening experience of what happens when we don't remember that our neighbors are not that different to us, and that's just always stuck with me,” she said.

Ever since this experience, Brodie has been particularly motivated by the Jewish practice of welcoming the stranger. A commandment that is repeated 36 times in the Torah, the scripture reminds Jews that they once “were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 19:33-34). “We hope to live up to this commandment and imperative in our work.” At the same time, Brodie doesn’t see these values as exclusive to Judaism.

She loves learning from her students how these same values can come from different life experiences, including other religious traditions.

“At Emma’s Torch, a lot of times either our students come from very strong backgrounds of faith, or are supported and have found friends through their religious community, whether that be a church or a synagogue or mosque,” she said. “Faith in general can be such a powerful tool to bring people together.”

These universal values of unity and welcome have motivated every step of Brodie’s career. After graduating from Princeton University with a degree in Near and Middle Eastern Studies, Brodie hoped to effect change through public policy.

Following two years of policy work at the Israeli Embassy in Washington DC, she became the press secretary for the Human Rights Campaign, a nongovernmental agency based in Washington D.C., where she publicized the organization’s international work. At the same time, she spent her free time meeting with women who inspired her next endeavor.

“I started volunteering at a homeless shelter and was really struck by the conversations about food that I would have with the women at the shelter,” she said.

Brodie wanted to cook with the women. She grew up learning to cook different dishes that connected her to her family’s religious and cultural history and inspired her pride in that history. She wanted to find a way to use food to do more than just feed these women. She wanted food to empower them, too.

“Recipes are not simply a list of ingredients. Each is wrapped in memories,” she said. “Cooking simultaneously defines and transcends our communities.”

Growing up, Brodie would visit her grandparents in South Africa, where they had found refuge during World War II. Both of Brodie’s parents were raised in South Africa and her grandparents still live there today. And during her earliest visits to her grandparents, Brodie learned to cook.

“My grandmother makes the most incredible milchika which are basically South African cinnamon buns. One of my earliest cooking memories is helping her make these.” While many American Jews have foods like bagels-and-lox to break their fasts on the Jewish High Holidays, South African Jews break their fast with milchika–a kind of cinnamon bun. Dishes like milkchika and the religious traditions around sharing them with family and friends has always inspired Brodie to see food as a powerful element in strengthening her faith and in enforcing a shared sense of identity amongst her community of faith.

For this reason, she encourages her students to embrace and celebrate their origins and home countries when they cook.

“Food helps our students understand that they’re not victims and that their work is valuable,” she says. Brodie says that she wants her students to see that each of their unique understandings of flavor and culture can actually enhance our communities and inspire our kitchens.

Inspired by her love of food and her conversations with the women at the homeless shelter, Brodie started reading about the restaurant industry. She read about widening labor gaps and about restaurants struggling to find talent to build out their kitchens.In May of 2016, Brodie left the HRC and began studying at the Institute of Culinary Education.

When she wasn’t learning to cook, Brodie was working to build out the organization of her dreams: a restaurant that would provide opportunities for the most vulnerable, a restaurant that would tell stories through its food.

She wanted to provide jobs for those who were left out. She wanted to bring people of different backgrounds and life experiences together in a space that felt comfortable to all of them; in a space where they could connect and realize that they could, in fact, work together. That space was the kitchen. And after graduating from culinary school in June of 2017, Brodie launched her first pilot program at Emma’s Torch.

Emma’s Torch began offering a free 12-week apprenticeship program with up to 500 hours of culinary and professional training. What’s more, students were paid to participate, allowing them to train full-time and cover expenses.

By the end of 2019, over 100 students had graduated from the program with professional culinary skills, English proficiency, and a community of support. Ninety-seven percent of the graduates had been placed in culinary jobs around the city.

And then, the pandemic hit. Like most people working in the hospitality industry in New York, many alumni were laid off or furloughed and Brodie was forced to close her training program and restaurant. She closed the doors of her restaurant and sent her students and staff home. But Brodie didn’t give up.

She turned her faith into action. The organization remained stable due to support from donors and a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Meanwhile, the Emma’s Torch staff began volunteering to work with students and alumni online. They hosted online cooking classes while also helping students and alumni apply for unemployment benefits. And Brodie innovated, working with old and new partners on her “Culinary Council” to restructure the business in response to the shifting industry.

After six months of solely online programming, Emma’s Torch reopened in October of 2020 with a three track program including the original culinary program in addition to two new tracks for alumni: the first being a community building program and the second a management-level leadership development fellowship for select program graduates.

Ruslan Abdraimov, a graduate of Emma’s Torch, participated in the fellowship. Abdraimov arrived in New York from Russia in 2016 with just $216 in his pocket and no understanding of the English language. Fleeing cultural and political persecution, he left everyone and everything he knew behind – for a chance to start over in America.

He knew one person in New York, who loaned him his sofa and told him about Emma’s Torch. Abdrainmov applied to the pilot program in 2017 and became a student in the first graduating cohort at Emma’s Torch.

Abdraimov remembers making 12 dishes on his graduation night. “I can’t choose a favorite,” he laughs. “It’s like asking [me] to pick [a] favorite child.”

But four of the dishes made him especially proud – a combination he calls “Winter’s Heat.” The roasted buckwheat katah, celery potato mash, sauerkraut stir fried with German sausage, and deep fried mushroom stuffed meatballs use all the vegetables available during winters in Russia. “Winters in a large part of Russia are long and cold. And you have to eat a lot to keep yourself warm,” he says with a smile.

Abdraimov describes his experience at Emma’s Torch as more than just an education in the culinary arts.“You know, it’s one thing when you hear about different countries and religions, but the other thing is, when you actually have a chance to meet that person and spend some time in a kitchen with that person, you know, and be around them every day, like for eight to 10 hours a day,” he said, nodding his head. “You learn a lot. And behind all that history, it’s something universal -- things like kindness, friendship.”

As Brodie shifts her focus to the students and alumni, the flames of Lady Liberty’s fire continue to burn at Emma’s Torch, which has transformed into a take-out cafe. As it was before the pandemic, the menu remains “New American cuisine,” cooked by New Americans.