On Thanksgiving Day of 2020, eight months into the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, Susanne Walther, a palliative care nurse working in New Jersey, received a text message from the wife of a former patient who died in the early days of the pandemic. The wife said that she thought about Walther, 61, often and that she would never forget her.

The message was a reminder for Walther that “small acts of kindness stay with people forever.

”What had she done? She simply “didn’t let them throw away her husband’s belongings,” she recalled. “Even when people are acutely grieving the loss of someone they love, they still have the kindness in their hearts to reach out to the clinicians who have cared for them.”

As the director of the palliative care team at University Hospital, a 519-bed hospital in Newark, New Jersey, Walther works closely with patients close to death. This means that she often talks with families when her patients are near the end of their lives, which would sometimes wear on her mental health.

The year of the pandemic has taken a toll on health care staff. Many frontline workers have left their jobs because of the pressures. Those who continue this work, like Walther, report that they are sustained, in part, by the thanks and appreciation they get from patients and their families.

The message meant so much to Walther. It reminded her that while they could not always save those suffering from COVID, they could offer comfort to them and their families.

In the early days of the pandemic, nurses and other frontline workers were especially important because few visitors were allowed in hospitals. Family members dropped their loved ones at the door of the emergency room and might never see him or her again.

The wife who texted that she would never forget Walther was one of them. Her husband was sick at home last spring and did not come to the hospital until the last minute. The staff attempted resuscitation with CPR, breathing machines and life support, but he still died in less than an hour at the emergency room. Right before the staff took his body out of the emergency room, Walther noticed his bag of personal belongings underneath the stretcher, which would get thrown away soon.

During the pandemic family members often called the hospital about clothes, wallets or watches that belonged to deceased patients, but the items were already gone, Walther said.

“It was such a panic with COVID. People were so scared that sometimes the belongings would be thrown in the garbage,” Walther explained. “Nobody wanted to touch them. People thought if they opened up the bag, they would get infected.”

Walther did not want this to happen to the wife of this patient, so she took the man’s belongings and planned to return it to his wife.

A month later, the wife and Walther met outside of the hospital. She handed Walther the small tropical plant inside her husband’s bag of belongings and insisted on Walther keeping it.

She told Walther, “Your kindness was the only thing that pulled me through my husband’s death. I cannot thank you enough.”

Since then, Walther has been watering it once a week, and the plant is thriving in her office at the hospital.

Born in 1959, Walther graduated from Rutgers University in 1985 with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and started working as a nurse in New Brunswick. To search for more challenging work, she quickly transitioned into the intensive care unit and worked as an ICU nurse for nearly 20 years.

From 1987 to 1990, Walther worked as an agency nurse in Bergen County, NJ. As an agency nurse, she got staffed in ICUs and critical care areas of different hospitals over the county based on needs. In 1990, Walther joined University Hospital.

Working night shifts from 7pm to 7am, she rotated all around different units in intensive care units, including the medical unit, the surgical unit, the trauma unit, and the neurological unit.

Patricia Murphy served as the director of the palliative care team at University Hospital until her retirement in 2013. She said that Walther is “one of the most specialties you will ever meet when it comes to caring for patients… families would tell me about this wonderful nurse who took such good care of the person they loved.”

After working in ICUs for 17 years, Walther burned out: “I found myself working very, very hard to keep people alive at all, you know, even though it appeared as if they were not going to survive.”

“I was just overwhelmingly morally distressed by some of the work that we were doing on people’s bodies. And I felt a great need to be sitting with families and talking to them instead of taking care of the patients,” Walther explained.

Around that time, Walther was thinking about graduate school programs, and Murphy suggested palliative care. In Murphy’s opinion, Walther already had all the skills needed to be an ICU nurse, but the skill she was missing was how to be with families in times of crisis.

In the following three years, Walther continued to work night shifts, split the duty of raising two children with her husband, and received her master’s degree in palliative care from New York University in 2005. Shortly after her graduation, Murphy hired Walther to join her team full-time at University Hospital as an advanced practice registered nurse.

“It was extremely morally and professionally satisfying to be moving into palliative care, and setting myself up to work with families, having meaningful conversations, and empowering them to have options and choices and making decisions about their loved ones,” Walther said.

Recently, Walther worked with a young woman in her late 20s, both of whose parents were critically ill after contracting COVID. Her father, only in his 50s, was on a ventilator at the hospital, while her mother was also on a ventilator at another hospital.

Having conversations with family members on the end-of-life of their loved ones can be tough, but Walther never shies away from those conversations. She felt obligated to inform the daughter that some families would find this type of prolonged life support unacceptable and wanted their loved ones to die peacefully, liberating them from the machines and the tubes.

Later that day, the mother of this young woman died at the other hospital. The daughter called the hospital and said that she wanted her father taken off life support and any treatments to be discontinued. As the medical note suggests, the daughter wished his father to have a natural death and be at peace with his wife who had just passed.

Walther still choked up when talking about this case. “I really didn’t want to call her and have this conversation because I knew it was going to be a very hard conversation,” Walther said. “And yet, I feel like if I never told her this and never gave her this opportunity, she never would have been empowered to consider that she could actually let her parents die on the same day and be together wherever she thinks they are, after they die.”

Although Walther has many intimate conversations with patients and their family members, she does not keep in touch with them afterward the service. However, working in a small community where many people have limited health care resources, Walther has helped multiple families through multiple losses.

After Murphy retired in 2013, Walther became the new director of the palliative care team at University Hospital. Currently, the palliative care team has four people, including two advanced practice registered nurses, one social worker, and one licensed counselor.

When COVID first hit New York City last year, tens of thousands of people died. The operating rooms at the hospital were closed, and most of the staff got relocated. Despite relocations, the palliative care team supports not only patients and families but also their colleagues at the hospital.

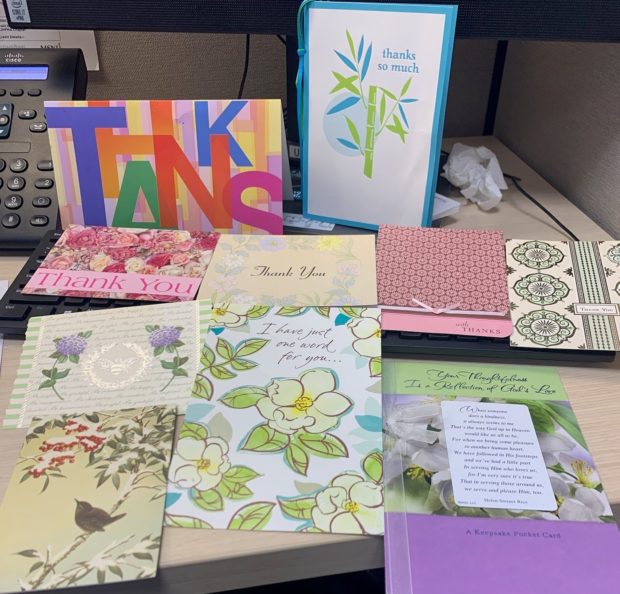

“One of the things our team was talking about, through the surge last year, was how little we felt that we could actually do for people,” Walther said. “But we have so many more thank you cards from families showing such appreciation for the smallest, tiniest way that we helped them connect with their loved ones.”