Day Seven: History, Hope and Homecoming

BELFAST - The last day of our trip through Ireland started again with a traditional Irish breakfast in the Europa Hotel. The rainy, gray morning skies of Belfast contrasted the occasional green on the streets: a reminder that it was the eve of St. Patrick’s Day. Our class departed each our own way as our day was dedicated to individual reporting and some sightseeing.

Dina Katgara went to Best of 3, a live comedy show at the Black Box in Belfast, to report on comedians who weave the aftermath of the Troubles into comedy. It gave her a thought-provoking perspective into how people in Northern Ireland cope with stereotypes about religion, as well as trauma. There were some dark jokes that we have come to expect from Irish humor. One of the comedians held up his favorite toilet paper brand, Regina Blitz, and made a joke about cleaning up the blood from Bloody Sunday with it.

Renata Carlos Daou interviewed an asylum seeker from Iraq who works as a photojournalist in Belfast. They talked about his experience as a Muslim and immigrant in a country that still predominantly consists of both Catholics and Protestants.

Natalie Demaree and Genevieve Charles spent the day reporting in County Down at a St. Patrick’s Day Prayer pilgrimage. More than 150 people from all over the world attended the rainy two-mile walk from Saul Church, the first church in Ireland, to Down Cathedral, where St. Patrick’s tombstone is located. This pilgrimage has roots dating back to the 1950s and was led by a combined clergy of both Catholics and Protestants. The walk was followed by a church service at Down Cathedral where both Catholics and Protestants participated.

Other students explored Belfast and other areas in Northern Ireland. Daniel O’Connor wandered around the city and was intrigued by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) paramilitary murals he stumbled upon at Donegall Pass in South Belfast. After wandering through a few blocks in the quiet neighborhood, O’Connor crossed the train tracks and soon realized he was back in a Catholic neighborhood, just by seeing a Palestinian flag and a Gaelic school.

Samuel Shepherd visited a recently completed mural on a peace wall — or, more accurately, a separation wall — in the predominantly Catholic area of Falls Road. It conveyed a poem by the late Palestinian poet Rafaat, who was killed in an Israeli airstrike in December. One section of the mural portrayed a child with a shamrock T-shirt, a child with a Palestinian keffiyeh and a girl with a South African flag holding hands in solidarity. On the other side of the wall, the West Belfast Cultural Society commissioned a placard honoring the close political friendship between the United Kingdom and Israel. While these etchings were physically close to each other on the wall, they were worlds apart in messaging.

Meanwhile, Katie Moody, Meghnad Bose and Trisha Mukherjee took a bus tour along the northern coast of the country. Driving by shining green pastures and a turquoise ocean rippling with waves, our reporters were overwhelmed by the beauty of Northern Ireland. They saw natural sites that appeared as settings in the popular HBO series "Game of Thrones." They also visited an Irish whiskey distillery and saw the outline of Scotland in the distance. Eventually, they arrived at the Giant’s Causeway, a seemingly magical area with basalt columns formed by an ancient volcanic eruption. An Irish legend tells another story, of a giant named Finn McCool who built a path to cross the Irish Sea to face the Scottish giant Benandonner, his rival. Benandonner, afraid of the meeting, ripped up the path and fled back to Scotland — leaving the scene as how it looks today. Despite the rain and wind, walking along the cliffs and the many stairs of the Giant’s Causeway was one of the highlights of their time in Ireland.

I dedicated my last day to interviewing people who experienced personal loss during the Troubles. It was part of an article I am writing about a law enacted by the British government in September. It says that Troubles-related inquests that are not finished by May 1 will be shut down. During my time in Derry and Belfast, I spoke to both loyalists and Republicans on their losses.

In the morning, I sat down in the Piano Bar of the Europa Hotel with Susanne McKerr, whose grandfather John was killed by the British Army during the Ballymurphy massacre. “Regardless of who the perpetrator was, what the incident was, what your identity is, the trauma is the same for us all,” said McKerr.

I then headed down to southwest Belfast, which is one of the Catholic hubs of the city. I interviewed Paul Crawford, whose father was killed by the UVF in 1974. In 1977, a man with UVF connections was arrested for the murder of his father, but it was only last year that Crawford received an acknowledgement that the UVF was responsible. After an hour of talking, Crawford showed me around the Catholic neighborhood, home to one of the hunger strikers during the Troubles.

During my journey back to the Europa Hotel, I crossed the “peace walls,” which flew Palestinian flags. I thought about the aftermath of the conflict in Northern Ireland and how it relates to ongoing conflict today — the intergenerational trauma, the mental health struggles and substance abuse problems individuals told me about. It made me contemplate: Do we as journalists report on the aftermath of conflict enough? What does it mean to go back to normal?

In the late afternoon, Dr. William Kitchen, a member of the political party Traditionalist Unionist Voice and an acquaintance of our guide Dr. Barbara McDade, came to the Europa Hotel to speak to some of us about the economics of Northern Ireland and the process of integration in the education system. Kitchen discussed the complexities of reaching a stable peace in Northern Ireland due to ongoing conflicting ideologies and economic conditions.

That evening, the class reunited for dinner at Deanes restaurant, where we were accompanied by Dr. Gladys Ganiel, who is a professor in the sociology of religion at Queen’s University Belfast. Ganiel talked about trends of religion and secularism in Ireland, after which we enjoyed our three-course meal in the private backroom of the restaurant.

During dinner we each shared our most significant moment from the trip, and we toasted our fellow classmates and faculty. Dr. McDade ended our evening by reading a poem by Seamus Heaney about war and peace:

Human beings suffer,

They torture one another,

They get hurt and get hard.

No poem or play or song

Can fully right a wrong

Inflicted and endured

…

History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracle

And cures and healing wells.

After a week traveling in Ireland and Northern Ireland, we learned about religious identity, conflict and the rocky path to reconciliation from a wide variety of speakers and local residents. The poem was a powerful reminder of the responsibility for us as journalists and storytellers to bear witness to other people’s stories and, while hoping for a “great sea-change” in the future, to keep on reaching for that further shore.

Edited by Samuel Eli Shepherd

Day Six: In Belfast, a City Still Learning Peace and Healing from the Past

BELFAST – After another traditional Irish breakfast buffet of eggs, beans and black pudding, we departed Londonderry for Belfast. This time, the ride was sleepier, as we watched the countryside roll by and reflected on the trip so far.

Like Londonderry, memories of the conflict were alive in Belfast, with the majority Protestant city, the largest in Northern Ireland, draped in Orange Order flags and Irish tricolors alike.

Our bus arrived early at the Europa Hotel, billed as “the most bombed hotel in Europe.” Driver Ben took us on a quick loop through a nearby Protestant neighborhood, Sandy Row, where we were greeted by murals of the Protestant King William of Orange and Queen Elizabeth II. The pubs in the area flew Israeli flags — a stark difference from what we saw in the predominantly Catholic Derry, where sympathies were heavily pro-Palestine.

As we pulled back around to the Europa, our driver cautioned us not to wear any political memorabilia from Derry while walking around Belfast, lest we offend anyone. He said we’d be able to know if we were in a Protestant or Catholic neighborhood by the art and flags.

“[It is] totally crazy, but that’s just the way things are,” he said.

Charity in ‘No Man’s Land’

After dropping off our bags at the Europa, we set out for Youth Link NI, a peace-building youth organization that is unique in that it officially involved both the Catholic and mainline Protestant church leaders, according to our guide, Dr. Barbara McDade, who once chaired the organization.

The charity’s headquarters sit in a “no man’s land” area of West Belfast, near a Protestant enclave of the predominantly Catholic part of the city. “Peace walls,” like we saw in Londonderry, divide Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. Here though, some stand over 40 feet high. Although the risk of petrol bombs and missiles was less of a threat than during the Troubles, both McDade and our driver insisted that the barriers provided psychological protection to both communities.

The walls were not the only harsh barriers in the neighborhood. McDade led us on a walk that included a stop outside an Orange Order lodge, blocked off by high fences with spikes that curved outward at the top.

She then led us to a walled-off building, complete with additional high metal barriers, watchtowers and cameras. What looked like a military outpost was simply the local police station in Belfast, McDade explained. On the same road, was a gate that McDade said was manually closed each night to prevent Catholics from crossing into the Protestant neighborhood.

Here, McDade shared with us the history of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, the police force during the Troubles that was 97 percent Protestant. The peace process led to several changes in the police force, now called the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). Affirmative action increased the number of Catholic officers. Still, Catholic PSNI officers often face violence from dissidents of their own communities, McDade said.

“It’s still considered too dangerous for [PSNI officers] to be on foot,” she said of the neighborhood. “The threat, particularly from dissident republicans, is still quite high.”

We saw a memorial to the Springhill Westrock Massacre across the road, commemorating another tragedy at the hands of the British Army.

Youth Link makes a point to employ asylum seekers for its catering services — including the lunch of curried chicken, vegetables and rice we shared. We also sipped tea and coffee while mingling with Youth Link employees.

After lunch, we gathered in a circle with Joe McKeown, a Catholic and the director of Youth Link, around an eclectic pile of flags, clothing and religious regalia from Ireland and around the world. A portrait of Queen Elizabeth sat over a Palestinian flag. A Gaelic football jersey was beside a Ulster Volunteer Force banner — an illegal symbol of the Protestant paramilitary in most contexts. And an American flag was right beside a Confederate flag — something that he said once made a group of visiting Americans so uncomfortable, they wouldn’t enter the room.

“These symbols do have power,” said McKeown. A few people winced as he accidentally stepped on the U.S. flag, proving his point.

McKeown told us that his grandfather was killed by a British soldier’s crossfire. Soon after, papers reported that he was an IRA agent. The trauma that impacted his family in the wake of the tragedy had a significant impact on his life. By his teen years, the sight of a British flag would cause him anxiety, he said.

“My body would go into shivers, I would feel threatened,” he said. Since then, he’s been on a “journey of reconciliation.”

He even tried to meet the soldier who’d killed his grandfather. The soldier had been 18 at the time.

“Kids with guns, trained to kill,” he said.

'How Do We Remember?'

Next, an interfaith panel joined us to talk about Ireland’s minority faiths. With representation from the island’s Baha’i, Romanian Orthodox, Muslim and Hindu communities, we discussed how the growing diverse groups fit within the Irish story.

“It’s still being written,” said Adrian Cristea, a Romanian Orthodox leader of the Dublin City Interfaith Forum.

After the panel, McKeown brought us to Clonard Monastery, in a neighborhood with deep Catholic roots. On the way there, we passed another gate that separates the neighborhood and locks from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. Beside a towering “peace wall” we stopped at a memorial to IRA members and civilians killed in the conflict.

“My mother would not be comfortable with me standing here,” McDade, a Protestant, said.

McKeown said there are two difficult questions Belfast residents have to ask themselves: How do we recognize the dead, and how do we also acknowledge that there are victims on the other side of the wall? “How do we remember?”

In the monastery, some students lit a memorial candle for peace, at McKeown’s suggestion.

After a quick dinner on our own, we headed to Belfast Cathedral for a St. Patrick’s Day concert by Anúna, the original musicians behind the ’90s Irish hit Riverdance. Toward the end, the group’s leader, Michael McGlynn, from Dublin, introduced the song Pie Jesu. His version, composed in 1998, commemorates a bombing in Omagh, in the Northern Ireland county of Tyrone. The bombing killed 29 people, months after the Good Friday Agreement was signed on April 10, 1998.

“I don't particularly want to talk about the context,” he said. “Everyone here has a story about the Troubles.”

Edited by Ann W. Schmidt

Day Five: Northern Ireland's Journey Towards Peace and the Bloody Sunday Legacy

LONDONDERRY – Today, our class began exploring tumultuous divisiveness and violence in Londonderry's recent history — and ended with an uplifting message of unity and friendship across religious divides.

After breakfast at the Maldron Hotel, we followed Northern Ireland guide, Dr. Barbara McDade, into the Bogside to learn more about the somber echoes of past conflict and the resilience of its people.

Our first stop of the day was The Museum of Free Derry. Walking down a slope into the Bogside neighborhood, we immediately noticed political posters and slogans in every direction. The streets were filled with flags from nations with which locals identify, including Palestine, Basque, Catalonia and Bosnia. Murals paid tribute to the innocent lives lost during Bloody Sunday when British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march in the Bogside. There were also posters opposing the Good Friday Agreement and supporting the 32 County Sovereignty Movement, a political movement that is against the British rule of Northern Ireland.

McDade explained that members of the group ask “What are the 30 years of war if you still accept the control of the British over Northern Ireland?” in opposition to the Good Friday Agreement, which ended most of the conflicts of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict that segregated the population between Catholics and Protestants.

But the prospect of a united Ireland still seems distant, McDade explained. Despite nationalist sentiments, economic and trade opportunities and benefits like universal healthcare often dictate voting behavior.

After seeing the influence of the conflicts in the streets of the Bogside, we reached The Museum of Free Derry, which opened in 2007 to memorialize the events that occurred in the city known as ‘Free Derry’ from 1968 to 1972. This era encompasses the civil rights movement, the Battle of the Bogside, Internment, Bloody Sunday and Operation Motorman. Located in the middle of the Bloody Sunday conflict zone, it was right outside the museum that British officers wounded three men and killed two others.

The visit to the museum had a personal touch with the family history of the museum guide. Our guide, Eoin Yates, 30, wasn’t yet born on Bloody Sunday but has a personal connection — his great uncle, Patrick O’Donnell, was wounded after throwing himself across a woman to shield her from gunfire.

Yates explained other tactics employed by the authorities during the conflict, such as adding glass to rubber bullets to maximize harm. He described the contemporary relevance of these historical events, showing the parallels of modern instances of injustice. "‘Bloody Sunday’ is something that happens around the world,” he said.

Yates also shared that many visitors, particularly those from Britain, don’t know about the events that led to Bloody Sunday until they visit the museum.

In the years following the atrocities, the struggle for justice and recognition of Bloody Sunday continues. Yates discussed the ongoing legal proceedings against Soldier F, a former British soldier on trial for two murders and five attempted murders. Yates also criticized recent legislative efforts that seem to undermine the quest for accountability.

The Museum of Free Derry is not just a memorial, but also a means of engaging with global patterns of state aggression. Yates believes in the power of shared experiences to foster understanding and solidarity. "If we can use that experience to help others, then that’s what we have to do," he said.

After the museum, our class dispersed for several hours of reporting time.

Ellie Davis, Katelin Moody and Emma Paidra visited Oakgrove Integrated College to learn more about integrated schools in Northern Ireland, which attempt to bring together children from both sides of the primary religious divide in Northern Ireland — Catholics and Protestants. They explored why the schools are still such a small segment compared to maintained (Catholic) and controlled (Protestant) schools.

Indy Scholtens interviewed Susan Gibson of Derry Well Woman about the Legacy Act. They talked about Gibson growing up in Derry during the Troubles. She founded Derry Well Woman because she believes that women suffer most often from conflicts yet don’t receive any special care.

Refael Kubersky, meanwhile, traveled back to Dublin to report at a mosque — he will meet up with our group in Belfast tomorrow.

As we mentioned before, stay tuned to read these pieces in the coming weeks.

Later, at 6:00 p.m., we gathered for dinner, joined by guests Bishop Andrew Forester from the Church of Ireland, Bishop Donal McKeown of the Catholic Church, Rev. Gordy McCracken from the Presbyterian Church, and Rev. Stephen Skuce of the Methodist Church. Surrounded by green and gold banners in preparation for St. Patrick’s Day, we learned about their journeys to faith and their initial interactions with Christians from other denominations. Overall, there was a shared optimism regarding the efforts of various churches to foster peace in Northern Ireland.

Edited by Trisha Mukherjee

Day Four: Onto Derry, Where an Imperfect Peace Persists

LONDONDERRY - On Wednesday morning, we checked out of Gresham Hotel in Dublin, met our bus driver, Kevin, and began our trip to Derry. (Or is it Londonderry? More on that later.) Most students slept on the bus, curled up in their seats as the rain pattered down the windows. Others had a variety of conversations on journalism, the conflicts in Ireland and Israel-Palestine and Cadbury chocolate while we cruised through the hills of the Irish countryside.

Midway through the bus ride, Trisha Mukherjee broke out her white ukulele and played a variety of songs, accompanied by Professor Ari Goldman on the harmonica. Classmates sang along and took photos and videos of the spontaneous performance.

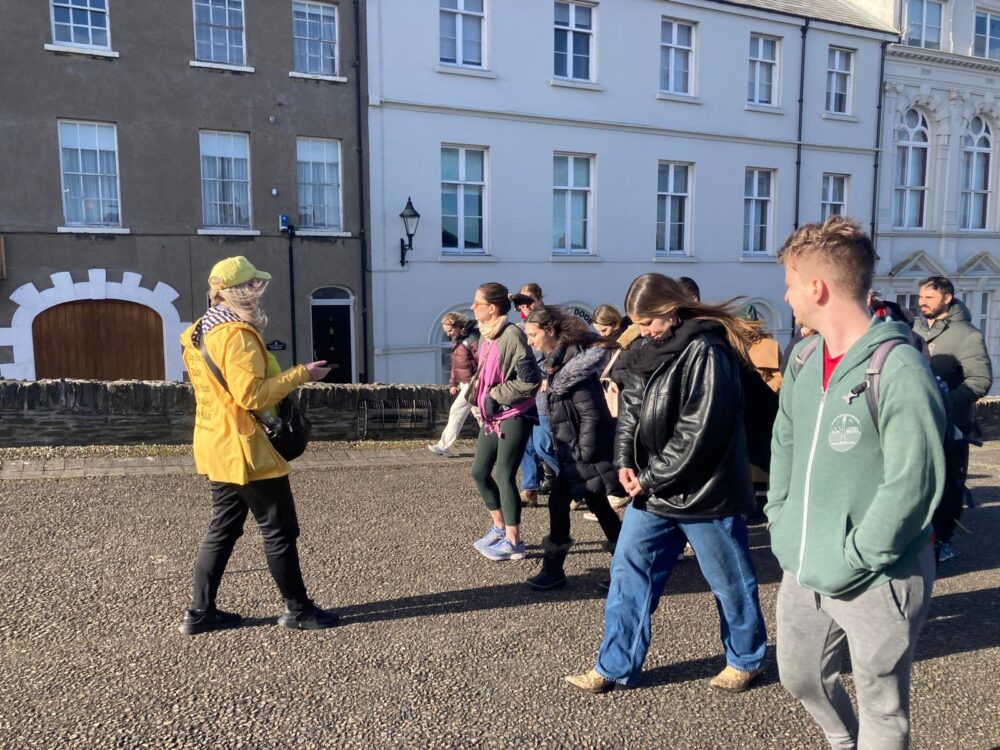

Around 2:20 p.m., we arrived at the Maldron Hotel in Derry and promptly embarked on a tour of the city led by Charlene McCrossan. Her late father, Martin, started Martin McCrossan City Tours during the Troubles. Charlene, who took over the business, is also the youngest tour guide in the United Kingdom to have received the Blue Badge, a prestigious certification for giving tours.

McCrossan led the tour around Derry, beginning with the River Foyle, which surrounds the city from almost all sides. She talked about the era of emigration from Ireland after the Great Famine. According to McCrossan, there are 75 million people in the world that claim Irish ancestry. “There’s an Irish pub in every capital in the world. Two or three if you’re lucky,” McCrossan said, echoing Ian Bermingham’s earlier point that celebrated the Irish people's diaspora culture.

She walked us through Derry’s founding from the 17th century, including the history of the building of the city’s infamous walls, making Derry the youngest fully intact walled city in the UK.

According to McCrossan, 72% of the current population of Derry is Catholic, and 28% is Protestant and other religious groups. But is it Derry or Londonderry? It’s clear even locals are undecided — with Catholic Irish nationalists mostly preferring the former and Protestant loyalists mostly the latter. Some signs show the “London” crudely scratched out (and on at least one sign, it had been written in again over the graffiti paint). Despite relative peace in the city for over 20 years, both loyalists and Irish nationalists still feel under attack in the city.

McCrossan peppered her tour with several references to the Netflix show Derry Girls. She spoke about the nostalgia it brought as she watched it and how it jogged her memory of the smaller details of her Protestant schooling as a Catholic during the 1990s. “More importantly, it’s educating our children as well,” she said. Later, the class even posed by a mural of the famous five protagonists!

McCrossan also broke down years of conflict between nationalist forces in Derry, showing us the cannons that remain in the walls from the siege of the city in 1689 and detailing the the Troubles, from the three-day riotous Battle of the Bogside in 1969 to Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British troops opened fire on unarmed protestors in the city, killing 13 at the scene.

Around 5, we got to tour the First Derry Presbyterian Church and hear more about the church's history from volunteer Joe Cuwan. He described the stained glass and how elaborate it is for a Presbyterian church. He then explained the reasoning behind why the burning bush is the symbol of Presbyterianism. There are hardships in life, but knowing that God is there gives comfort, Cuwan said.

We ended the day over a long, lingering dinner at the Walled City Brewery, in which Professor Greg Khalil proposed a “game” of answering questions about ourselves and our feelings about the trip thus far. It was enlightening and emotional to learn what our fellow classmates were experiencing. We walked back to the Maldron, noticing how the shape of the Peace Bridge over the river takes the form of a handshake: a wavy path to peace as imperfect and unpredictable as our journey through Ireland has been.

Edited by Samuel Eli Shepherd

Day Three: The Sun Rises — As Do Tensions in Dublin’s Religious Communities

DUBLIN — We started our third day in Ireland at 8:30 a.m. by walking along the south bank of the River Liffey to Christ Church Cathedral. The Protestant cathedral was founded almost 1,000 years ago under the reign of Viking King Sitriuc, according to the church’s website.

Housed within the cathedral are several storied artifacts, such as the metal-encased heart of Archbishop Laurence O’Toole, patron saint of Dublin. The stone crypt — one of the largest in Ireland — contains a copy of the Magna Carta and a mummified cat and rat which were found trapped inside the organ pipes and are now affectionately called “Tom and Jerry” by the Irish, our tour guide Ian Bermingham told us.

After the tour we met with Very Rev. D.P.M. Dunne, dean of Christ Church Cathedral, who shared an overview of his own religious history. The dean said he grew up Roman Catholic in County Cork, which he described as being deeply religious.

“The whole town literally came to church,” he said.

Seminary school opened his eyes to philosophy and religious inquiry, setting him on a path to convert to Anglicanism and eventually become a leader in the Church of Ireland.

Dunne spoke about aspects of Catholicism with which he takes issue, namely the faith’s stance on human sexuality and treatment of women. Catholicism is dogmatic, he said, comparing the religion to mushrooms, which are kept in the dark to grow. Whereas Anglicism is a “living faith,” which adapts based on the experiences of its practitioners.

“I’d prefer a thinking congregation,” he said.

He noted, however, that Catholicism in Ireland is undergoing a period of change. He said he’s noticed a shift under Pope Francis, and described faith in Ireland as experiencing a “questioning” or “in-between” phase.

While there are far fewer practicing Catholics in Ireland today than there were several decades ago, many people remain nominally Catholic, said Dunne, adding that the state is secular, but religion remains a strong undercurrent.

The dean said that through immigration, people have brought their religions to Ireland, which has been one of the greatest developments for the country.

“All of that has diluted the monochrome experience of faith in Ireland,” he said.

Also of note, we learned that Dublin’s sister diocese is the Diocese of Jerusalem. Some Protestants in Ireland still associate Palestinians with the Irish Republican Army, said Dunne, because of the IRA’s historical connection to the Palestine Liberation Organization.

On our way to the next stop, we passed the Abbey Theatre. Bermingham filled us in on the Gaelic revival movement, during which plays written about historical Irish figures were performed on the Abbey Stage. “[The Irish] were imagining their future by reimagining their past,” said Bermingham.

Since more than half of Ireland’s population identifies as Roman Catholic, according to 2022 census results, we rounded out the morning by walking through St. Mary’s Pro Cathedral. Several of us stopped to observe the “Candle of Innocence,” which burns in memory of survivors of clerical and institutional abuse.

Notes From The Field

The sun came out for a moment as we parted ways for another afternoon of reporting and exploring the city.

Ellie Davis visited a classroom at a nondenominational school to learn about their ethical-based education model and how it compares with Catholic schools’ religious-based education.

Ann W. Schmidt left Dublin and traveled to Northern Ireland’s first co-op farm in Larne. She witnessed volunteers feeding chickens, Shetland sheep and pigs.

Natalie Demaree took a peaceful stroll through Glasnevin, Ireland’s National Cemetery and home to the world’s largest collection of Celtic crosses.

Eleanor H. Reich met six men holding a sign that said “Grandfathers Against Racism.” They told her they stand there once a week in response to what they view as a rise in racism and xenophobia towards migrants in Ireland.

Other classmates bought souvenirs, toured Trinity College and grabbed lunch.

Kosher Dinner and Discourse at the Synagogue

In the evening, we went to the Dublin Hebrew Congregation, the only Orthodox congregation in the Republic of Ireland.

Edwin Alkin, president of Dublin’s Irish Jewish Museum, led a talk on Jewish Irish history. He told us about the rapid growth in the local Jewish population as persecuted Jews from Russia and Lithuania immigrated to Ireland.

The discussion shifted from the past to the complex present of the Jewish experience with the arrival of guests from both the Israeli expat community in Ireland and the local Jewish community.

We paused the conversation momentarily for a Kosher dinner. Before digging in, Prof. Goldman taught the group an English version of “Shalom Aleichem (Peace be Upon You),” a Jewish song traditionally sung in Hebrew.

During dinner, there was a spirited debate between the Irish Jews and Israeli expats about their views of antisemitism in Ireland. Most of the local Irish Jews insisted antisemitism was not felt in Ireland, while the Israelis accused them of turning a blind eye to the growing antisemitic rhetoric in the country.

Overall, the experience was tense but insightful. In class, Prof. Goldman told us that where there are two Jews, there are a million opinions, and this is exactly what we experienced.

When we left dinner, a pleasant surprise awaited us: a double decker bus all to ourselves. We rushed in with child-like enthusiasm and headed back to the Gresham Hotel.

Edited by Ann W. Schmidt and Natalie Demaree