LONDONDERRY – On Wednesday morning, we checked out of Gresham Hotel in Dublin, met our bus driver, Kevin, and began our trip to Derry. (Or is it Londonderry? More on that later.) Most students slept on the bus, curled up in their seats as the rain pattered down the windows. Others had a variety of conversations on journalism, the conflicts in Ireland and Israel-Palestine and Cadbury chocolate while we cruised through the hills of the Irish countryside.

Midway through the bus ride, Trisha Mukherjee broke out her white ukulele and played a variety of songs, accompanied by Professor Ari Goldman on the harmonica. Classmates sang along and took photos and videos of the spontaneous performance.

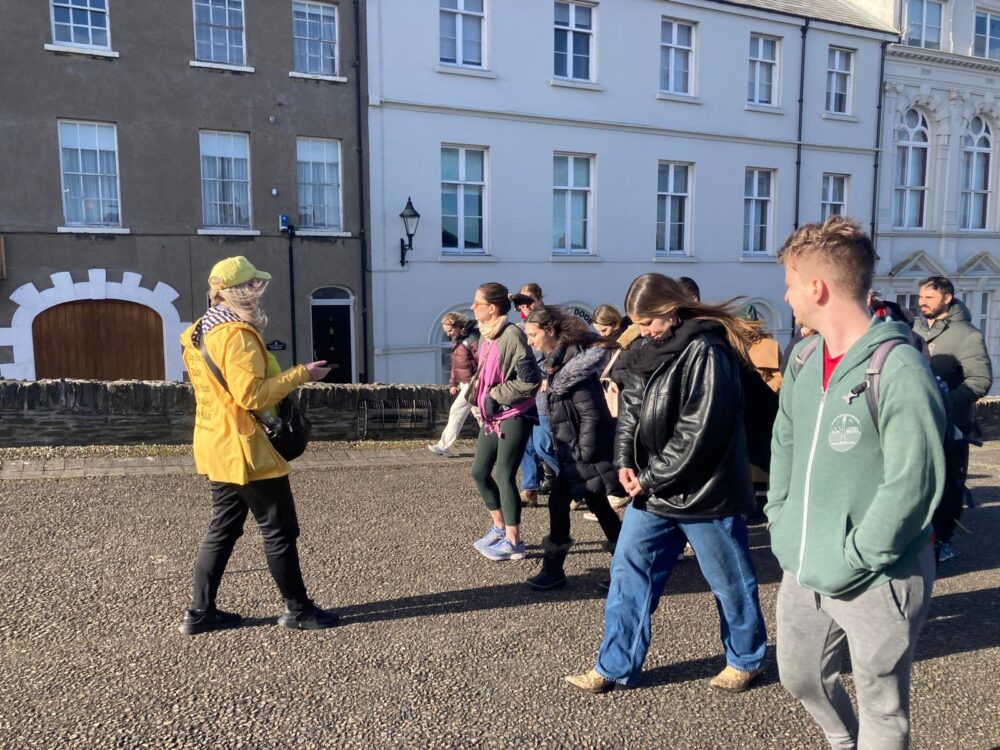

Around 2:20 p.m., we arrived at the Maldron Hotel in Derry and promptly embarked on a tour of the city led by Charlene McCrossan. Her late father, Martin, started Martin McCrossan City Tours during the Troubles. Charlene, who took over the business, is also the youngest tour guide in the United Kingdom to have received the Blue Badge, a prestigious certification for giving tours.

McCrossan led the tour around Derry, beginning with the River Foyle, which surrounds the city from almost all sides. She talked about the era of emigration from Ireland after the Great Famine. According to McCrossan, there are 75 million people in the world that claim Irish ancestry. “There’s an Irish pub in every capital in the world. Two or three if you’re lucky,” McCrossan said, echoing Ian Bermingham’s earlier point that celebrated the Irish people’s diaspora culture.

She walked us through Derry’s founding from the 17th century, including the history of the building of the city’s infamous walls, making Derry the youngest fully intact walled city in the UK.

According to McCrossan, 72% of the current population of Derry is Catholic, and 28% is Protestant and other religious groups. But is it Derry or Londonderry? It’s clear even locals are undecided — with Catholic Irish nationalists mostly preferring the former and Protestant loyalists mostly the latter. Some signs show the “London” crudely scratched out (and on at least one sign, it had been written in again over the graffiti paint). Despite relative peace in the city for over 20 years, both loyalists and Irish nationalists still feel under attack in the city.

McCrossan peppered her tour with several references to the Netflix show Derry Girls. She spoke about the nostalgia it brought as she watched it and how it jogged her memory of the smaller details of her Protestant schooling as a Catholic during the 1990s. “More importantly, it’s educating our children as well,” she said. Later, the class even posed by a mural of the famous five protagonists!

McCrossan also broke down years of conflict between nationalist forces in Derry, showing us the cannons that remain in the walls from the siege of the city in 1689 and detailing the the Troubles, from the three-day riotous Battle of the Bogside in 1969 to Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British troops opened fire on unarmed protestors in the city, killing 13 at the scene.

Around 5, we got to tour the First Derry Presbyterian Church and hear more about the church’s history from volunteer Joe Cuwan. He described the stained glass and how elaborate it is for a Presbyterian church. He then explained the reasoning behind why the burning bush is the symbol of Presbyterianism. There are hardships in life, but knowing that God is there gives comfort, Cuwan said.

We ended the day over a long, lingering dinner at the Walled City Brewery, in which Professor Greg Khalil proposed a “game” of answering questions about ourselves and our feelings about the trip thus far. It was enlightening and emotional to learn what our fellow classmates were experiencing. We walked back to the Maldron, noticing how the shape of the Peace Bridge over the river takes the form of a handshake: a wavy path to peace as imperfect and unpredictable as our journey through Ireland has been.

Edited by Samuel Eli Shepherd