Day 3: Baptisms in the Jordan and the View From an Israeli Settlement

In the trusty hands of Zaki, our driver from East Jerusalem, we loaded into our big blue bus and departed Nazareth for a drive through the Jordan Valley toward Bethlehem.

In stop-and-go traffic, under a milky sky, we passed through rolling hills, a rainbow of greens, browns and purples, as we made our way to the West Bank and its Israeli-occupied settlements, which are illegal under international law.

The falling rain around us was an expression of the melancholy that professor Ari Goldman said he felt leaving Nazareth. To lift our spirits, he led the Hebrew song “Boker,” (or “morning” in English), our daily routine. “Morning comes, it’s time to work,” we all chimed in, finishing the lyrics.

We cut through the north of Israel, arriving at another place important to Christian pilgrims — the site on the Jordan River where Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, as recounted in the New Testament.

Sabri, an archeologist and guide, said baptism here is a ritual of purification and a way of entering the community for many worshippers. For those who have been previously baptized, it is a renewal and recommitment to their faith.

A cheer rang out from a crowd of pilgrims as a young girl burst from the water, eyes closed, waves rippling from her body and water cascading down her face. Some pilgrims tentatively dipped just their hands into the cool murky water. Another woman filled up plastic bottles of the water Christians believe to be holy. She’ll take them home and boil the water to use in future rituals.

Sabri’s wife, Abeer Mashni, a Palestinian from East Jerusalem, has strong views about the site. For her, it's a symbol of “refugees, borders, families separated and occupation." Standing nearby are heavily armed, green-clad Israeli soldiers — the Israeli Defense Forces keep watch over the Jordan border, just about halfway across the site, separated by a floating rope. “We need to see religion in political context,” she said.

We then drove to nearby Jericho for a quick lunch of hummus, pita and grilled meats, passing a large red sign. “The Entrance for Israeli Citizens is Forbidden, Dangerous to Your Lives and Is Against The Israeli Law,” it warned.

Leaving Jericho, adjunct professor Greg Khalil directed our attention to the Russian compound atop the Mount of the Olives, to orient us to Jeruselem proper on our drive to Efrat, an Israeli settlement. Among the buildings, there's one particularly notable distinction between the Palestinian villages and the Israeli settlements which populate the West Bank. Sitting on Palestinian roofs are black and white water tanks—residents' limited source of running water, which is subject to running dry. Israel controls 85 percent of the water in the West Bank, with control over licensing and distribution. It's a distinct difference from settlements with flowing running water and no visible tanks.

We walked through an open door at settler Sara Tesler’s house in Efrat. A grand entrance hall led into a large living room, where a semicircle of chairs were pushed together to join two sofas into a circle. A panoramic glass window stretched around two sides of the living/dining room. Tesler highlights the view of hilly landscape, two neighboring settlements and the Israeli wall. In the middle is a small patch of olive trees. Tesler doesn’t hesitate to tell us that the landscape is Palestinian land and that she, her family and her community are not allowed to go there.

Seven years ago Tesler made the decision to move her family from New York to Efrat. “I had this feeling that in America I was watching Jewish history unfold," she said. "Here, I am part of it." She took leave from the school she worked at in Riverdale and originally planned to spend ten months living in Efrat. Her family never left.

Tesler and her neighbor Kally Kislowicz told us we could ask them whatever we wanted; they assured us they wouldn’t be offended. Student Anvita Patwardhan asked what they would like the media to better represent about settler life. “I’d like to see the settler side humanized a little better,” she responded, adding that she’d prefer articles focusing on positive relationships being built among settlers and Palestinians.

Tesler said she had Palestinian friends from the neighboring villages. She was quick to tell us of her Palestinian carpenter whom she sees regularly. We asked whether she would be friends with Palestinians who are not supportive of her viewpoint. To this, she said no. “I would be too scared.” She said also never drives into Palestinian areas, noting she would never drive into Jericho. She takes detours to avoid interactions that make her anxious.

Tesler shared her views on the Israeli army. “They are portrayed as bloodthirsty and aggressive,” she said. She knows many of them personally and thinks the army should be humanized. More than 170 Palestinian civilians, including at least 30 children, were killed across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem in IDF-led raids last year.

Two of Tesler’s teenage daughters drifted in and out of the living room to join the conversation. One of them begins her military service in two years. While there are a few exceptions, military service is compulsory for both Israeli males and females beginning at the age of 18. Tesler pictures her daughter waiting at a bus stop wearing her army uniform and is anxious for her safety, saying this would make her a target. Kislowicz has three sons who will all be going through the military in the coming years. “It’s going to be a big part of our lives,” she said. They are both grateful Israel has power.

Aromas of the family’s dinner floated into the living room, signaling the time for us to leave. As we drove away, the volume rose on the bus as conversation broke out.

Day 2: From Mary’s Well, to a Church Halfway House to an Ahmadi Mosque

By Ania Gruszczynska and Nora Zaim-Sassi

This morning, we met Bassam Hakim, our tour guide around Nazareth. Hakim grew up in the city in a family devoted to hospitality.

"Nazareth is my passion," he said, by way of introduction.

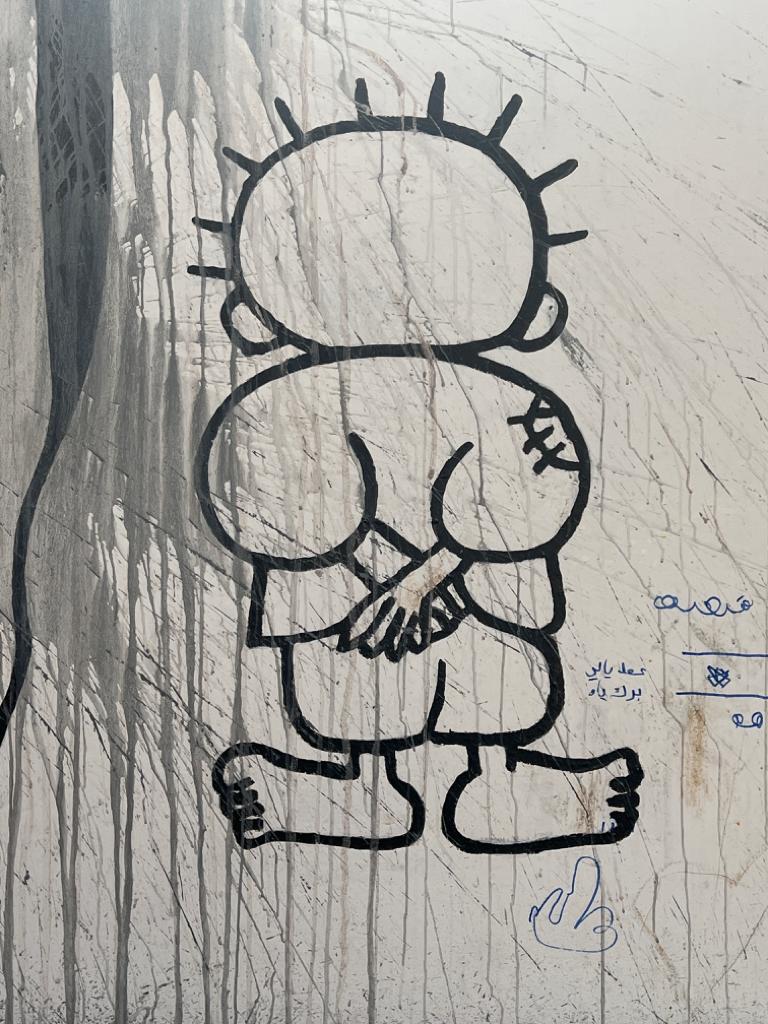

We made our first stop at Rehov Hagalil Street’s graffiti wall. Although Nazareth is in Israel, and everyone here is an Israeli citizen, the city is heavily Arab — 80% Muslim and 20% Christian — and support for the Palestinian cause is clear through the multitude of graffiti expressing solidarity for the struggle. One drawing says, "My homeland is not a bag, and I'm not traveling." The art is sometimes vandalized, but seems to always return, Hakim says. Another mural showed a little man turned away from the viewer, because he's always looking home. Hakim tells us this is a typical Palestinian symbol that is found throughout the Middle East.

Nazareth’s story centers on the Annunciation — the moment when Christians believe the Archangel Gabriel told a 13-year-old Jewish girl named Mary that she would give birth to God. We visited multiple religious sites in the city that claimed to be the site of this event.

One such site was Mary's Well. The original well was two sided, one for men and the other for women.

We then approached the Palestinian Orthodox Church of St. Gabriel, which also commemorates the Annunciation. The church was built in the form of a cross and split into two sections by a beautifully adorned iconostasis with scenes from both the New and Old Testaments. One side was dedicated to female saints, including Saint Barbara, an early Christian Lebanese martyr. At its furthest wing we looked into a water spring, still trickling, where Mary was said to have experienced the Annunciation. Coins lay on the bottom representing wishes and prayers.

We arrived at the Church of Annunciation. Monumental but stark, the structure was consecrated in 1969 and has been a Catholic site of worship ever since. Those countries who contributed the most to its erection are memorialized in a passage of Madonnas with Jesus, each visibly rooted in the local culture — Chinese, Brazilian, Polish or Ukrainian. We craned our necks to see a great geometric dome — a white lily representing purity, devotion and the Annunciation. Below it were two levels, the bottom one representing a fundamental darkness from which a Christian must emerge to enter light. The nave of the Basilica was the very cave that is believed to have held the New Testament scene. There is a marble altar illuminated in delicate blue light before which people pray. Letters on it spell: “Verbum Caro Hic Factum Est” — the word became flesh here.

As we walked through the city’s narrow streets, with mostly beige brick buildings, the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, hummed in the background. The call came from the White Mosque, the first mosque in Nazareth, constructed in 1805.

We traveled next to Haifa, a mixed Arab-Jewish town. We heard stories of coexistence and cooperation rarely found elsewhere in Israel, as well as stories of struggles and suffering.

Before 1948, Haifa had a population of 70,000 Arabs, but all but about 3,000 were expelled following the Arab-Israeli war, according to Jamal Shehade, the director of the House of Grace, a welcoming place for all regardless of religion, a rehabilitation center for prisoners, impoverished families and programs for children and elders.

Currently, the House of Grace houses 17 formerly incarcerated individuals in its rehabilitation program. Of these, 15 are Muslim, one is Druze and one is Christian. The House of Grace helps them find jobs, pay off debts and reintegrate into society.

As Easter, Passover and Ramadan approach, the House of Grace is preparing packaged meals of nonperishable food for 300 families throughout Haifa. Shehade, inspired by his father, who started this mission 40 years ago, serves and welcomes everyone into a space that does not discriminate, he said.

“This is not a missionary organization— we welcome anyone coming here asking for support as a human being.”

This theme of unification carried on into conversations with Imam Murad Odeh, Jamal Shehade’s friend and the Imam and General Secretary of the Ahmadiyya Shaykh Mahmud Mosque, which peers over the beach in the Kababair neighborhood of Haifa.

As we entered the congregation, a group of Jewish children headed out and Odeh greeted us. Odeh described his openness to all Jews, Christians and Muslims. He told us about a Jewish man wearing a kippah who prayed at the mosque. He told us — and anyone — “come and join me.” Odeh regularly leads interfaith discussions and panels with priests, rabbis, locals and foreigners.

We all silently entered the mosque, the women with their hair covered, with one man just wrapping up his prayer facing the center of the room, toward Mecca, with the Shahada in green Arabic script. Odeh passionately spoke about the importance of focus during prayer. “God warns people who come to pray without concentration,” he said.

He provided further insight during a conversation in his office, filled with books.

“Today all of us are suffering from wrong interpretations of holy scriptures,” he said. He continued to recite verses of the Quran and translate them into English, explaining interpretations that can lead to kindness, unity and altruism. Through this lens, he spoke highly of Haifa’s diversity and its residents' relatively successful coexistence.

“Haifa is the holiest city, in my perspective,” he said. “I think people make places holy — not the stones.”

Keep an eye out for Henrietta and Noelle’s post tomorrow about our trip to Bethlehem and Jericho!

Day 1: In the Footsteps of Christian Pilgrims

The New Testament describes the miracles Jesus performed — many of them near the Sea of Galilee, in the northwestern corner of Israel, where he spent much of his adult life. The Sea of Galilee, the lowest freshwater lake on Earth, was the focal point of today’s trip for us on our first day in the Holy Land.

At 7:50 a.m. sharp, we hopped on a bright blue bus, still jet-lagged and groggy from our late arrival in Nazareth the night before. After driving about two hours north, we were greeted by the sun sparkling on the lake on which Jesus once walked, Christians believe.

Our first stop was the Church of the Beatitudes, which was packed with pilgrims from all around the world. Built by Antonio Barluzzi in the 1930s uphill from Byzantine ruins where Jesus delivered the Sermon on the Mount. The church overlooks the Sea of Galilee. To the west of the lake are the towns of Galilee and Tiberias, and to the left was the Golan Heights.

It was here where our tour guide, Akiva Sygal, explained the significance of the lake, and why fish play an important role in Christianity.

Jesus began preaching after he turned 30. Surprisingly, there aren’t any accounts of what his life really looked like before this time. When he became the leader of a new faith in a place where Judaism was still very much the dominant religion, he started preaching to fishermen in the sea’s coastal towns — those men became his first disciples, and fish became a symbol in Christianity. — The symbol of fish was also a way for Christianity to differentiate itself from Judaism and represent a fresh new idea, which has now become one of the world’s biggest religions.

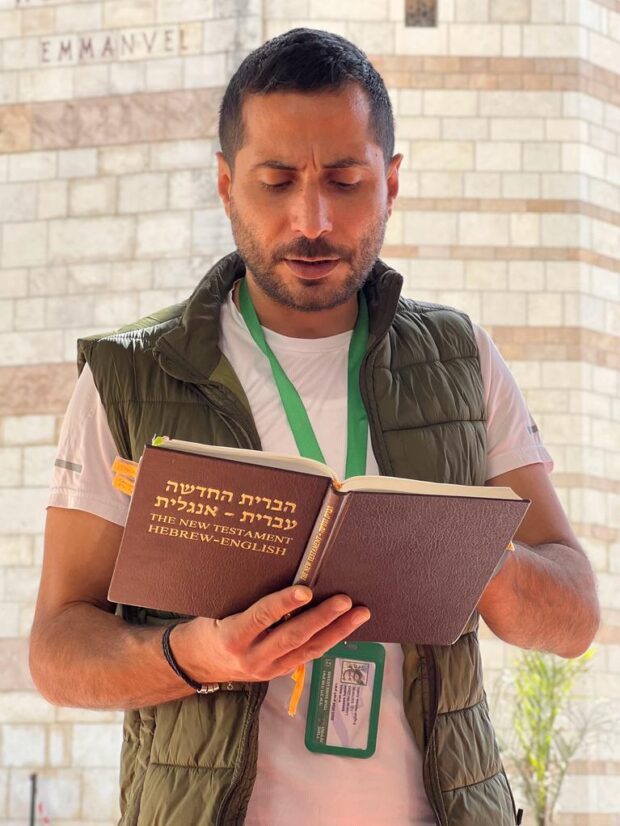

It was at the Church of the Beatitudes where we were introduced to a little book called the New Covenant. The Bible, the holy book for Christians, is composed of the Old Testament (which those who practice the Jewish faith refer to as the Torah) and the New Testament, which describes Jesus’s life . In Israel, most buildings, homes, and hotels already have the Old Testament. For those who are Christian, they can get a small book called the New Covenant which just contains the New Testament.

Our next stop was the Capernaum, a fishing village located on the northern shore. This is where it was believed that Jesus had given his first sermon in the synagogue.

For me, the most interesting thing about Capernaum was the history of how it slowly transformed from a Jewish town to a mixed Jewish-Christian community. In its early years, Christians practiced their faith secretly. Disciples designated a house in the Jewish village as a Church, and they slowly started coming to pray covertly. As Christianity grew more dominant, a formal church was built in its place. Ruins of a massive synagogue stand nearby.

It is here where we learned the verb “to capernaum,”–to be messy (a term Fiona actually already knew).

The next stop was the Church of Multiplication, a Roman Catholic church located at Tabgha, on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee. We were introduced to the Christian story of the 5 loaves and 2 fish, with which Jesus was able to feed 5,000 people. The courtyard was peaceful, with a small area for 2 fish and an olive tree.

We traveled next to the coastline town of Tiberias, a Jewish town. It’s an important area for the Jewish community today, but this was not always the case. When the Roman Empire swept past Jerusalem, they burned down the Jewish temple, and the community found refuge in Tiberias. It became a holy site for the Jewish community, where it could visit the graves of rabbis, scholars and poets who lived in the city. While the Jewish faith considers graves to be a space of impurity, they also represent history, and in time may become holy sites.

Before 1948, Tiberias was a mixed Arab and Jewish town, and in 1948, it became the first Jewish town of Israel. We visited the tomb of the Rambam, or Maimonides, and what remains of an abandoned mosque where Muslims once docked their boats and completed daily prayers.

Our next stop was onto a large wooden boat, which took us around the Sea of Galilee

This was the first time during the day that we were able to sit back, relax and enjoy Arabic songs and one of the most iconic pieces of music, “Here Comes the Sun” by the Beatles.

Refreshed and on the verge of an afternoon siesta, we headed to our final stop of the day - Kibbutz Ein Gev. It is here that we met a longtime Israeli resident of the kibbutz. He told us the history of kibbutzim, Israeli community settlements–often agricultural–where members live, work, and eat together.

The two most important values of a kibbutz are cooperative and communal living. In fact, we learned that the kibbutz was a safe space for refugees who fled the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Our conversation Was briefly interrupted as a group of children drove nearby on their toy tractor, waving at us before we headed back to Nazareth. The speaker told us that kibbutzim were uniquely Israeli, and that while other communities throughout history have tried to live communally, each culture had to find a version of that works for them.

“You can take the idea of a kibbutz, but you can’t copy it” exactly, he said.

Stay tuned for tomorrow’s adventures told through the eyes of the lovely Ania and Nora!