Day 8: Last Supper and Return to New York

It was not yet 6 a.m. when we were roused from our beds by a hotel-wide security alarm at the Batsheva Hotel in the heart of Jerusalem. The announcement was in Hebrew, and none of us could understand it. Was it a fire? A bomb? Our WhatsApp group kept buzzing: “What on Earth was that?” we asked. Five minutes later, a text from our guide Eli Philip calmed everyone’s nerves. “It’s all good. False alarm,” he said. We shuffled back to bed, bleary-eyed, and slept for a few more hours before we began our last day in Israel.

We woke up (for real) to gloomy skies. At the breakfast table, Philip methodically distributed the stash of spices he had purchased in the Old City for those looking to bring home a souvenir. The smell of sumac filled the room. We had the morning to ourselves, so a few people went out to report or explore. Laura visited the Razzouk Tattoo Studio, the oldest tattoo shop in the world, and returned beautifully inked with a Picasso dove. Laura chose the image, a symbol of hope from Noah’s Ark, to remind herself of her hope for humanity and her belief in people, she said.

With that, we bid adieu to Jerusalem and boarded Lilian to head to Tel Aviv.

There, we made a quick pit stop to pick up Jack Saba, a team member of the Telos Group. We then met Robi Damelin, a remarkable woman who is the spokesperson for the Parents Circle - Families Forum (PCFF), a joint Israeli-Palestinian organization of more than 600 families, all of whom have lost a family member in the conflict.

Damelin joined PCFF after her son David was killed by a Palestinian sniper in 2002. She has since dedicated her life to the cause of reconciliation and nonviolence. Recalling the moment she received the news of her son’s death, Damelin told us, “all of my life I spoke about coexistence and tolerance. That must be ingrained in me because one of the first things I said was, ‘You may not kill anybody in the name of my child.’”

Damelin, who described herself as “rather rebellious,” mentioned the difficulties she faced growing up in South Africa. Ignoring apartheid laws, she dated an Indian man against her parents’ wishes. Her personal story was painful and moving, yet she filled the room with warmth. She carried herself gracefully and spoke with conviction.

After our meeting with Damelin, we met Dahlia Scheindlin, one of the local experts who helped us in shaping our reporting topics. With a master’s degree in theological studies from Harvard Divinity School and a PhD in political science from the University of Tel Aviv, Scheindlin is a public opinion expert for political and social campaigns in Israel. Scheindlin answered our many questions regarding the conflict and touched on reporting techniques that could help us with our journalism moving forward. She addressed questions that had come up for us in our reporting. Sarah asked about claims she had heard from Christian clergy and advocates that Americans were involved in many of the attacks against Christian holy sites in Jerusalem. Scheindlin wasn’t aware of that trend, but noted that Americans tend to play an outsize role in Israeli politics – on all sides – because they tend to be financially better-off, and in many cases moved to Israel for ideological reasons, from more politically active backgrounds.

Back on Lilian on our way to Jaffa, Saba, who is Christian, shared his incredible love story with a Muslim girl. Early in their relationship, they faced backlash from both families and community members.

We were at the edge of our seats waiting to hear how the story ended, when our attention was redirected to the sun setting over the Mediterranean and the echoing call for the evening prayer from a seaside mosque in Jaffa. After acknowledging the moment, we turned back to Saba, who finished his story. With a lot of perseverance, secret dating and determination, he told us, the couple stood their ground until their families came around and accepted their decision to get married. Today, they live in Tel Aviv with their daughter.

“These relationships, although rare, can be found here,” Saba said.

During Saba’s story, Laura was nearly jumping out of her seat. She had been interviewing people from interfaith relationships all week, and this was just the kind of story she was looking for. Stay tuned to read her piece in the coming weeks.

We then headed to our final dinner in Israel at a Jaffa restaurant called Par Derriere. As we settled in our seats, it dawned on us that this was the last time we were all going to eat together at the table in the Middle East.

Goldman shared the founding story of our class, Covering Religion. After a trip to Israel with his family in the early 2000s, a representative of the Scripps Howard Foundation asked what he would do with his class if he had money, he recalled. “ I would love to take my students to Israel too,” he responded. That is how we came to be at the table with him, more than 20 years later.

Although experienced in traveling with students, Goldman acknowledged that this trip had been particularly challenging. He highlighted tough conversations between him and Khalil that shed light on the complexity of the conflict and how there was a lot he needed to reflect on personally. Khalil and Goldman toasted to each other, acknowledging that the difficult conversations had brought them closer. We took turns sharing lessons we learned during the trip and questions that still lingered.

We began this trip as strangers. After sharing 10 days together, we returned to New York City as friends with whom we shared a deep connection and experience with. In the weeks since the trip, we’ve remained a tight-knit group, digesting what we saw and the news that comes out of Israel/Palestine.

Day 7: 'The Past is my ID': A Visit to Dheisheh Refugee Camp

The wheels of the Lilian, our trusted bus, spun on empty streets this morning. It was Saturday, Shabbat — the Jewish day of rest. Roads that are normally busy and chaotic lacked any sign of life. But as soon as we left the bus at Bethlehem’s Dheisheh refugee camp, we were welcomed by blasting music, children running across houses and the owner of a coffee cart who pressed Adjunct Professor Greg Khalil to buy a round for the group.

We were welcomed by our local guide, Hamza, 35, who was born and raised in the camp and works with children at the Ibdaa Cultural Center, a local organization focused on community-building. As we walked through the center, walls of awards and athletic trophies greeted us.

We sat down and Hamza —who joked that he's “a bit afraid of journalists” — told us his story.

While he spent his whole youth only 40 miles away from the sea, he swam for the first time at 22, and he remembered finally feeling free. Years later nothing has changed. When Hamza asked the camp’s children one day if they had ever seen the sea, only one child raised his hand; he said he had seen the sea on his television.

The Israeli army routinely comes into the camp in the middle of the night to make arrests, he said. They come by jeep, sometimes shooting tear gas or rubber bullets, while children in the camp fight back by throwing stones.

“The day is for us,” Hamza said. “The night is for them.”

Established in 1949, a year after the start of the Arab-Israeli War and the associated displacement of Palestinians, Dheisheh is located in the south of Bethlehem. The land was originally filled with tents, but as the years passed, the United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNWRA) replaced them with concrete buildings. At the time, many of the camp’s inhabitants refused the switch, Hamza told us, because that would mean accepting that they were staying in a refugee camp. Many still hold keys to the homes they were forced to leave. But in the end, they had no choice.

The units were no bigger than three by three meters — Hamza called them “sardine boxes.” He grew up in one such box, which he shared with two parents and three siblings. As we walked through the camp and saw the residents’ cramped quarters, the reality of how small and confined that space is sank in.

Over time, Palestinian refugees started to build their own houses in the camp. As we walked through the narrow streets, walls of gray concrete towered over us. They are all built close to each other; after last month’s earthquake in Syria and Turkey, Hamza noted that if the same thing happened in this camp, it would be like “dominoes falling.” Some homes looked unfinished, with entire walls missing. Others appeared vacant, except for the laundry hanging to dry outside.

There are approximately 14,000 Palestinians in the camp. and more than half are children. We met several running around as chickens clucked in the background. “The camp is one family; it is full of life,” Hamza said.

The camp relies on humanitarian aid and sometimes loses basic services. Earlier this year, UNWRA, which supports health and education, was on strike, forcing schools and clinics to close for over two weeks.

Hamza lived in Paris for a few years and traveled to Sweden, Norway and Greece, but he has since returned back to his homeland. The fence around the camp came down in 1995, but Hamza emphasized the importance of staying in the camp, rather than moving away and starting a new life. Despite the many discomforts of living in the camp — including lack of reliable electricity or running water, to name a few — many of its inhabitants want to maintain their refugee status because it keeps them connected to their land and reminds the world that they have a right to return home.

“The past is my ID,” he said. “We are healing the past’s future.”

Driving back to Jerusalem, we reflected on the fact that the city felt like a whole other world, just 20 minutes away from the camp.

The rest of the day was filled with our own reporting, leaving Noelle Videon with her hands covered in Palestinian soil at the Tent of Nations, where she wheelbarrowed about olive plants across the property. For hours, she planted trees alongside other volunteers.

Others returned to Jerusalem, to explore and interview. Sarah Cutler spoke with a representative from the Greek Patriarchate about rising attacks on Palestinian Christians, while Laura Esposito spoke to interfaith couples. Hanna Nebiyu Vioque, Fiona André, Sherry Fernandes and Greg Dobak decided to visit Razzouk Ink, the oldest tattoo shop in the world, popular with pilgrims seeking a permanent reminder of their trip to the Holy Land.

As evening came and Shabbat ended, we headed to a bittersweet last dinner in Jerusalem. Apart from good food and cocktails, the night was filled with kind words and admiration. We toasted each other, realizing that, on this emotional trip, near strangers had turned into friends.

Day 6: Breaking Bread in Bethlehem, ‘Holy FOMO’ in Jerusalem

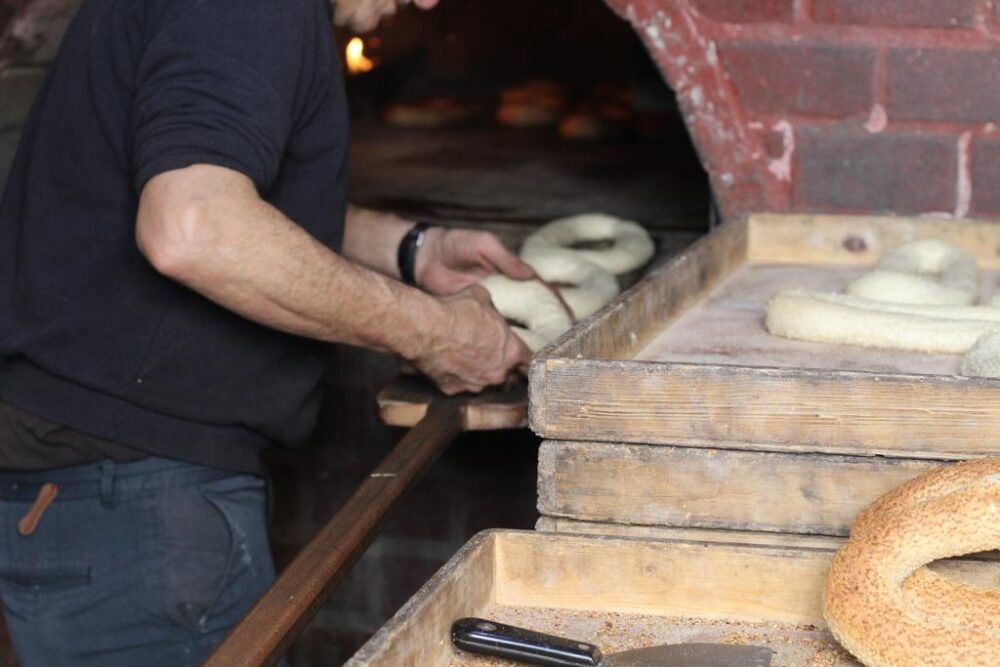

On Friday, we met tour guide Saleem Anfous, who took us through the Old City of Bethlehem. Our first task was to taste it. We stopped by a bakery for ka’ak al-Quds, a bread covered in sesame seeds that’s also called the “Jerusalem bagel.”

The bakery owner estimated that his traditional wood-fired oven, passed down by many generations of his ancestors, is anywhere from 700 to 800 years old. We got a bag of ka’ak bread fresh out of that oven to share. We split the freshly-baked, oval-shaped bread into four pieces per person. I opened up my piece, releasing the steam, and sandwiched falafel into its center.

Anfous described the city of Bethlehem, with its population of 33,000, as “tiny” and close-knit. Indeed, throughout the tour, our guide was greeted by friends and family on the street. So was Adjunct Professor Greg Khalil, whose family is from nearby Beit Sahour.

Anfous approximates that within the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Jerusalem, there are five million Palestinians (with Palestinian ID). Of that population, 40,000 are Christians. They’re a minority, but they punch above their weight.

Anfous cited Palestinian Christians’ contributions to the larger community. “We’re the salt of the community,” Anfous said, saying a small sprinkle of salt in one’s food is enough to get its flavor just right.

After sharing the story of Christ’s birth, Anfous delved into the history of the Church of the Nativity. Not only is it considered the oldest church in the world, it is also the holiest site for Christians.

In 70 AD, following the destruction of the city of Jerusalem, Christians gravitated towards a new superlative holy place: Jesus’s birthplace. Roman Emperor Hadrian ordered the building of the Temple of Venus, the Temple of Jupiter and the Holy Sepulchre — as a mockery towards Christianity, they were built on top of their house of worship. It wound up becoming a boon for the Chrstian faith as it allowed the church to remain preserved. Two hundred years later, the Roman Empire itself became Christian.

Unlike holy sites of so many other empires, this church has successfully avoided destruction. When we entered, we saw bits of the original floor, a remnant of the original Byzantine church that was built here in 335. High up on the wall were more mosaics, some of which were only recently uncovered.

Inside the adjoining Church of St. Catherine, signs were plastered along the walls that read “SILENCE.” Clergy and security staff roamed about to enforce the policy. Despite this, whispers abounded. When the choir began to sing "O Come, All Ye Faithful," a hush fell over the crowd. The walls reverberated as their voices echoed throughout the chamber. It was eerie, yet beautiful.

We hopped on the bus to make our way to our next destination: the Tent of Nations, an educational, collaborative Palestinian farm. After crossing the muddy threshold, we walked the dirt path leading to the site. The view of the hill was breathtaking — but in the foreground, trash was strewn along the sides of the path.

We gathered in Meladeh’s Cave at the behest of its director Daoud Nassar. The cave was cozy yet accommodating enough for our entire group. Along the walls were vibrant paintings of orange human figures against a bright blue background, sprinkled with quotes in dozens of languages. One read: “Peace, justice and conservation of the creation.”

Nassar’s family has owned this farm for more than 100 years — since the time of the Ottoman Empire. Despite such a storied history, his family has had more than its fair share of legal struggles to validate their claim to their own land. Beginning in 1967, the Israeli government required them to register their land in order to pay property taxes — a tough ask for a community built on the principle of handshake agreements as opposed to documentation.

Nassar said he's been involved in a legal battle over the land with the Israeli government for more than three decades.

But he hasn’t lost hope. In fact, that’s what his farm means to him. The planting of slow-growing olive trees represents the time investment and community effort required to maintain the land. The hands painted on the door represent people joining together to create something beautiful.

“Although the way for justice seems too long, too difficult, too complicated,” Nassar said, “we believe that one day justice will prevail.”

Our muddy and well-fed group piled back onto Lillian, our trusted bus, who carried us to Jerusalem, where we would spend our last two nights. In the late afternoon, as we approached Shabbat, we trekked to the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, for a tour.

Shelly Eshkoli, our tour guide for the afternoon, corralled the group into a small alley for a moment away from the crowds. “The hardest thing to find in the Old City is a quiet spot,” she said, as a passing car honked and we scurried out of its path.

Apart from leading nerve-fraying tours, Eshkoli is a biblical researcher, specializing in the women of the Old Testament — who she said have been “erased.” We all know Moses, she noted, but do we know the name of his wife? (Incidentally, one of my classmates did, but that is beside the point.) As we walked through the cobblestoned streets, polished from the footsteps of pilgrims and tourists, she explained how the city came to be divided into Christian Muslim and Jewish quarters: People lived everywhere but tended to concentrate close to religious sites that were important to their faith.

Eshkoli later stopped outside a small, stone-brick building, and pointed at a glass case affixed to the outside of the house. The Hanukkah candles were originally displayed on the window so that everyone could see the physical manifestation of the Jewish miracle. As she was explaining this, a man wearing all white (kippah and beard included), entered a kabbalistic synagogue, his pristine dress attracting curious glances within the group. For Shabbat, she explained, men dress in white shirts — the best of the best.

Fashion, in general, was a topic of curiosity on Friday. Some Ashkenazi Jews we saw were dressed in long, golden robes, unlike the black and white dress of the majority. This trend began hundreds of years ago, when the Ultra-Orthodox were first moving into the Jordanian-occupied territory and were living alongside Arabs.

Eshkoli explained that because they were quite poor, they began building their synagogue using loans from the Arabs, which they later defaulted on. In order to trick the lenders, who had come to mistrust them, they began dressing like rich Assyrians to emulate wealth.

We next visited the Western Wall, where we were reminded of a phrase Professor Ari Goldman used earlier in the trip — “holy envy” — meaning a wish to participate in another faith’s rituals.

Peeking out of the crevices of the wall were pieces of paper, on which visitors write wishes or prayers to converse with God. Eshkoll, however, told us she believed just thinking the prayer in the presence of the wall was enough.

At the wall, student Kelly Waldron said she felt “holy FOMO” (for the uninitiated, that’s “fear of missing out”) on the apparent catharsis experienced by the people surrounding us.

The sun was setting, and the air was charged by the hums, prayers and song of this congregation from all over the world. Wishes that had broken free scattered across the ground, like the suds of a wave in a sea of shuffling feet trying to make it to shore. As our group made its way to the exit, we could hear the Muslim call to prayer.

Day 5: Reporting in Jerusalem, and a View Behind the Wall

After days of gloomy skies, the sun returned to Bethlehem and Jerusalem, just in time for our first day of solo reporting. Most of us boarded our faithful steed, a bus we now call ‘Lilian’ at 9 AM (not so) sharp, and headed into Jerusalem. This morning also marked the first instance that our group was stopped by Israeli border police as we crossed from Bethlehem —land controlled by the Palestinian Authority — to Jerusalem. A man and a woman in green uniforms boarded our bus and requested our passports. After they made sure we all had identification, we made it across.

Before going our separate ways, a group of us followed our guide, Eli Philip, to Cafe Sira in Center City. Following a heavy few days of intense conversations, it was a refreshing break to sip on iced coffee and lemon tea, share sandwiches and chat at a table outside, relishing the sunshine that had evaded us the past two days. It was a busy day for all; students Kelly Waldron, Henrietta McFarlane, Greg Dobak and Hanna Nebiyu Vioque visited the Orthodox Jewish neighborhood.

Nebiyu Vioque went to the Ethiopian sector of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a small, sectioned-off area on the roof of the church. Nebiyu Vioque comes from an Ethiopian family, but struggled to communicate with the priest, who spoke only Amharic. She called her father, who is fluent in the language. Over the phone, he stepped in as an impromptu translator, while also engaging in an animated, laughter-filled conversation with the priest. By the end of the phone call, Nebiyu Vioque’s father was brought to tears, she told me. It’s significant to him and other religious Ethiopians that they have representation in the Holy Land, she explained.

Waldron, a native of Ireland, was invited to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day at the Representative of Ireland’s residence in Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem, where she mingled with other Irish citizens in the region. Waldron discovered the ambassador, Don Sexton, lived 20 minutes away from her family in Ireland.

While a few students stayed in Jerusalem until evening, most of our group headed to the museum of street artist Banksy’s Walled-Off Hotel, stopping first to walk along the adjacent Israeli wall, which the Israeli government began building in 2004, to block the main road from Bethlehem to Jerusalem in response, Israel says, to a wave of suicide attacks.

On the other side of the massive, graffiti-filled structure, is the tomb of Rachel, a matriarch from the Old Testament. Scripture says she died on a journey and was buried in Bethlehem, making her final resting place a holy site for all Muslims, Christians and Jews. Yet because of the wall, Palestinians don’t have access to the tomb.

The atmosphere in our group noticeably shifted as Philip guided us along the wall. It’s mostly covered with graffiti style-artwork, an initiative led by the infamous anonymous artist, Banksy. “Free Palestine,” “I Was An Angel And They Tear-Gassed Me”, “Forget Not the Tyranny of this Wall, Nor the Love of Freedom that Made it Fall,” were among the quotes that induced the pensive silence in our group. Right as we reached the street corner, and the Banksy Hotel was back in sight, we paused at a portrait of Holocaust victim Anne Frank, captioned with her famous quote, “In spite of everything, I still believe people are really good at heart.” A moment later, the sound of the Muslim call to prayer filled the streets. We stood transfixed, listening to the sound of the ritual and watching as the evening sun dipped behind the wall.

When we entered the Walled Off Hotel, we navigated through the museum inside, which explains the history of the wall, and the displacement and human rights violations Palestinians experience because of its existence. A video in the exhibit explained it simply: one persecuted group found its home, another lost its own. The United Nations asserts that the wall is illegal under international law and that Israel must stop building it and pay reparations to the Palestinian people. This was almost 20 years ago. “If you’re not completely baffled, you don’t fully understand,” a sign read.

With teary eyes and heightened emotions, we left the site and headed to dinner in Bethlehem with Reverend Sally Azar, the first ordained Palestinian woman. We ate hummus, salads and the traditional Arabic meal of mussakhan, then moved to a separate room for tea and a conversation with the pastor. She tells us she’s heard about all of the sites we’ve seen and is familiar with the emotions we’re experiencing.

“It’s something I experience everytime I come back,” she said.

Azar spent eight years studying theology in Germany and Lebanon before returning to Israel/Palestine in January and becoming an ordained pastor. As the conversation shifted to the wall, she shared her own personal experiences with it. She tells us it sometimes takes her hours to commute between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, a drive that took us 45 minutes that day. Still, she’s one of the luckier ones; a lot of Palestinians can’t legally travel between the two cities.

Palestinians “feel like second class citizens,” she said.

Choking up, Azar shared that the already-small Christian-Palestinian community dwindles more every day.

“I love my country, I love its people and I want to be there for them,” she said. “But at the same time, what can I tell them? Please stay?”

She emphasized her optimism in spite of increasing challenges as a stateless person and spiritual leader. “We always say hope is what the Palestinian people carry. If a Palestinian lost his or her hope, what's left?” she said.

“There are others still fighting and speaking out every day. It’s hopeful that social media has been helpful to raise more awareness. Our voices are sadly not heard, but we hope you and others can share our voices,” she said.

Resolved with this point of no resolve, we zipped up our coats and stepped outside into the darkness of Bethlehem.

Day 4: Rain on the Stones of Jerusalem: On the Ground in the Old City

The early-morning sun reflected off the rows of white houses of Bethlehem as we started the day. Storm clouds started to roll in as we packed into our blue bus that we’re affectionately calling Lilian.

As we started the journey towards Jerusalem, rain began to fall. There was a palpable energy from yesterday’s interviews with settlers Sarah Tesler and Kally Kislowicz. Both Professor Goldman and Adjunct Professor Greg Khalil took turns addressing that conversation as we passed through the checkpoint approaching Jerusalem.

At the American Colony Hotel, we met with our first speakers of the day, Palestinian journalist Dalia Hatuqa, based in Ramallah and focused on the Middle East, and Jalal Abukhater, a 28-year-old Jerusalem resident.

Hatuqa was quick to point out that she is not Israeli and is only allowed into Jerusalem on a permit. The conversation focused on the measures Palestinian residents of Jerusalem have to take to maintain their status as residents in the city, and controversial laws that the Israeli government often uses to force property transfers from Palestinian to Jewish residents. Non-Israeli Jerusalemites must show that their “center of life” remains in Jerusalem; this process can involve such measures as keeping food in the refrigerator in case of unexpected check-ins by authorities. This policy greatly complicates the lives of those who may have a partner or children in the West Bank, since it is difficult for those people to move into Jerusalem.

When the focus switched to what it is like living in Jerusalem, Hatuqa turned the conversation over to Abukhater. We embarked on a walking tour of the traditionally Muslim Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. Abukhater explained the Absentees’ Property Law, which transfers property to the state in cases where the government deems there is an absentee owner — usually in cases where the original owners fled during the 1948 war. Abukhater showed us the El Kurd home that was presented as an example of forced property transfer in a recent documentary, My Neighbourhood, by Julia Bacha.

We then walked to the Jaffa Gate of the Old City, where we met Walid Zahran for a tour through the narrow, winding alleys of the one-kilometer-square city that holds more than 200 historical monuments and religious sites significant to Muslims, Christians and Jews. Walid, a native and lifelong resident of the Old City, began his talk describing the history of the city’s walls built by Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent.

In the pouring rain, we entered the city and made our way to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The church was constructed on the Golgotha Mont, where Jesus was crucified.

At the entrance, pilgrims kneeled to kiss the marble slab at the place where Jesus’s body was laid. Dozens waited in line to see his tomb; one woman was so overcome with emotion that she started crying. In a corner, a group of people lowered their voices to pray while lighting candles.

At lunch, Goldman returned to the conversation with the settlers that had started on the bus, explaining his own ties to the country. “I have 100 cousins” in Israel, he said, much like Khalil, who has family living in both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Goldman used a metaphor borrowed from Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Isabel Wilkerson to describe the state of affairs in Israel and Palestine:

A country is like a house, he said, whose imperfections are the product of all its inhabitants. The condition of the house can’t be blamed on any single inhabitant, but that all of those who live in it have responsibility for what goes on there. Goldman connected this with the class’s response to yesterday’s conversation with two settlers, which elicited strong feelings. He urged the class not to blame any one actor for the larger conflict.

Khalil used the same metaphor but pointed out that his family — and that Palestinians in general — occupy a far less powerful position in that house, and that responsibility for fixing its problems is not shared equally. He urged the class to think about the role of power, and the baggage that comes with being in a less-powerful position. Khalil noted that in many situations, Palestinians and those with less power shoulder much of the burden of advocating for their rights, and highlighted the toll this takes and the physical risk it entails. He urged the class to reflect on why we assume that those who are oppressed must be the only ones to speak up for their communities.

The conversation brought into sharp focus the complexity and emotionally charged nature of the conflict, highlighting the way decades-old disputes that many of us had only read about affect the lives of real people.

We left the marketplace through the Damascus Gate to meet with Anshel Pfeffer, a journalist with Haaretz, who took us for a two-hour walk in Jerusalem’s Mea Shearim neighborhood, where Ultra-Orthodox Holocaust survivors settled after World War II. Over the years, the area expanded and is now home to a wide range of Jewish communities. On one street, men wear shtreimels, and large fur hats; women dress modestly. Smartphones are prohibited, in favor of kosher phones with no internet access.

“This is not a tourism neighborhood,” a young man yelled to us in Hebrew while we walked toward Beit Yisrael, an adjacent Ultra-Orthodox neighborhood. We stopped at Shabbat Square, a busy area during the week that is now closed to traffic on Shabbat after residents protested for a strict observance of the holy day. This visit pushed us to reflect on the dissensions and differences between secular and religious Jews in the country.

We ended the day amid the colorful stalls of the Mahane Yehuda market before heading back to the bus, happy to relax after this day in the rain. We climbed aboard wet and tired, and returned to Bethlehem. There was a consensus in the group for how lucky we are to be able to visit these places and talk with those who live here. We are led by a Columbia professor of 20 years, a self-proclaimed Zionist and writer for the New York Times alongside a successful entrepreneur, Yale Law School graduate and advisor for the Palestinian negotiations. These two individuals coming together despite all that might put them in opposition to show us a sliver of the land at the heart of civilization and religion. As the reality sank in of what could only be described as a life-changing trip, the clouds cleared and gave way to a beautiful orange sunset.