A New Buddhist Ritual: Chanting Online to Release the Souls of the Dead

A Buddhist passed away in New York City.

His funeral was two weeks ago. Only a limited number of family members were allowed at the scene because of the pandemic. Master Chang Xun and her “householders” from the Chen Meditation Center in Queens were unable to attend, so they decided to go online and chant with the family at the funeral service. Buddhists believe that the soul can be released from purgatory through religious changing.

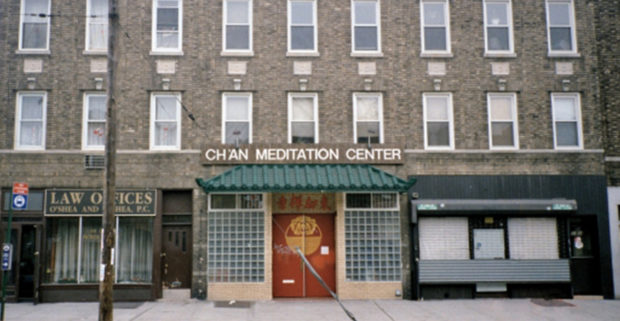

The long-distance chanting at the funeral was only one way that the Chen Meditation Center, located at Corona Ave in Queens, has been coping with the pandemic that swept through the globe over the last two years.

Chan Meditation Center in Queens, New York City. Photo courtesy: Chan Meditation Center’s official website.

At first, the center, like many other houses of worship, closed its doors. It gradually resumed its regular activities by holding hybrid classes and services, both online and in-person. On Sunday evenings, about a dozen members gathered in their temporary “Bodhimaṇḍa”, a place of enlightenment for Buddhists to sit down and meditate, which usually has one or more Buddha statues in it to watch the 2020 movie “The Father”–and discussed it after the screening. The film, starring Anthony Hopkins, is about an aging man who must deal with his progressing dementia. Half of the members sat in a circle, talking, while others were busy preparing homemade marshmallow cookies beside the window. At the end of the hall, a golden statue of Buddha sat quietly, staring at people from on high. A robot vacuum wandered leisurely on the floor below his feet.

Chang Xun said that online classes have actually increased the center’s audience. “Around 70 to 80 people attend online classes and meditations,” Chang Xun said. “Comparing to 30 people in the old days when we were meeting in person.”

Ming Shi, a householder at the Chen Meditation Center, said that online Dharma classes allow her to listen to different Master’s classes from different places. “We invited Master Sheng Dian’s disciple in Europe to discuss Dharma this Sunday since there are no geographical restrictions online.”

However, Masters, householders, and other participants are all hoping the activities can soon resume in person, especially because of the lack of empathy when talking online. “We cannot see each other’s facial expression clearly”, said Chang Xun. She’s also concerned that online classes have a strict time limit of one hour, while they can go longer when meeting in person.

Shi, as one of the organizers of young Buddhists’ classes in the New York area, worried about how sincerely young Buddhists can learn from online classes and chanting: “I don’t feel elderly Buddhists affected by the online classes very much. Young people did. Because there are lots of distractions in your life. if you are physically going to the meditation center and learning with others, you don’t have the chance to do other things, but you might do other things simultaneously when learning online.”

Despite online classes, Master Chang Xun must also cope with the lack of volunteers in the center during the pandemic. Usually, some familiar participants and householders in the center served as volunteers to cook vegetarian meals, do cleanings, and organize events, but during the pandemic, some volunteers cannot come to the center very often. Chang Xun herself had to take all their jobs.

That wasn’t too bad until one day she had to go to the market.

Chang Xun, like many Buddhists, is a strict vegetarian. She accidentally walked through several meat stalls in the market to get to the stalls that sell vegetables. She smelt the odor of fish and meats, and can’t stop thinking about when they were still alive. “I almost cried,” She said. “I can’t stand their suffer.”

The day after she had come back from the market, Master Chang Xun still thought about these creatures, even when she was teaching Dharma classes. “I can still smell them,” she said. She made a special prayer for the livestock she encountered at the market.

Now, Chang Xun seemed not to have to struggle anymore. Volunteers are coming back these days as the positive cases in New York started decreasing. The center expects more volunteers to come back in the following month.

However, their coping moments never cease. To Buddhists, Dharma itself is the way that they are trying to cope with any new situation in their lives–Asian hate crime, diseases, kindness, wars… etc.—even though this situation seems to violate their belief.

Anxious East Village Community Prays for Relatives Back Home in Ukraine

Among the worshipers at All Saints Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Manhattan on Sunday, Tetiana Geletei prayed fervently for her father.

Geletei’s whole family is in Ukraine, where her father has been called by the Ukrainian army to fight the Russian invasion. “I cannot connect to him,” she said. “I don’t know where he is now. Is he safe?” Her pitch rose as she voiced her last worry: “If he has something to eat at all.”

At the service, Pastor Vitaliy Pavlykivsky urged congregants to pray for Ukraine and to donate money to support the Ukrainian army. The church is located at 206 East 11th Street in the East Village.

A flier on a table near the prayer candles for sale at the church’s entrance listed a bank account and routing number for donations. “Ukrainian National Federal Credit Union has open account: ‘Help Ukraine’ for the Armed forces of Ukraine. Collected funds will be wired every day to support Ukraine,” it read.

At the end of the formal part of the service, when Pavlykivsky had blessed each of the worshippers individually, Iryna Rusyn, 22, asked where she could donate money to support the army. She’d brought cash with her.

Rusyn had spent more than an hour traveling to the church by train from Queens, she told me outside afterwards. She doesn’t have time to make the journey every Sunday. In fact, she’d only been to All Saints once before. But she needed to be there this week.

“I felt that I needed to pray for my country, for my people,” she said on the church steps, hands stuffed into the pockets of her long black faux fur coat. Despite the cold, she’d made plans to meet up with a friend, a fellow Ukrainian, to go to a rally in support of their homeland.

After she had left, most people still lingered in the church. “Because of this event, of course they pray a bit longer now,” she explained.

Inside, children ran from side to side along the back aisle and bounded up and down the stairs to the balcony where some of their mothers were singing in the choir. Four kids wore the colors of the Ukrainian flag, which flew outside the church door.

The mood among the adults was somber and anxious. One woman wiped her eyes repeatedly during prayers. She hastily stepped outside twice to take calls on her cell phone, pressing it to her ear before she’d even reached the door.

Geletei, 30, a human resources coordinator, is here in the United States by herself. She described the how church’s atmosphere felt changed: “It’s different because people are hurt.”

The president of the church, Oleh Mykulynskyy, had left New York for Ukraine that morning, Geletei said.

“He served [the] Ukrainian army before he came to the United States. So he felt like he needs to go back and try to help,” Geletei said.

As the whole church prayed for Mykulynskyy, his wife sang upstairs with the choir, as she does every Sunday.

“When we found out that he left, half of the choir was crying,” Geletei said.

Rusyn was not the only person who came to support the church community because of the ongoing crisis. Pavlykivsky greeted a small group of Georgians in English and thanked them for their prayers and support, and a young woman named Samantha whose grandparents had belonged to the church after they had immigrated from Ukraine visited for the first time. But for members, being together was emotionally intense.

“It’s really hard to be here. It’s really hard,” Geletei said. “Because, you know, you can feel the pain.”

“Praying helps,” Geletei said. “And all this long prayer at the end, it was specifically regarding the war. So we were praying for stopping the war, we were praying for strength for Ukrainians.”

No Compromise In Obedience

Ask one million people how they feel about COVID-19 lockdown measures, you will get 1 million strong opinions. Ask a Sufi what they think about lockdown, and you will get a reserved and resigned response.

“Obey Allah, obey the Holly Prophet Muhammad, and obey those who are authorities. This is the basis of our life.” This is the guidance of Shaykh Diomande Suleyman, leader of The Most Distinguished Naqshbandi Sufi Order in New York/New Jersey. “Those authorities can be male; they can be female. They can be president, they can be governor, they can be a health director, a police officer, a supervisor – whoever is in that position of authority, you must obey that person.”

Obedience is a key part of being a Muslim and Sufis have raised this attribute to something of an art form. In the four stages of Sufism, the first two stages – sharia, the religious laws, and tariqah, the inner mystical path – govern how to live your life outward and inward to achieve spiritual enlightenment. Their literal translations from Arabic both refer to a type of pathway that must be followed in order to achieve the higher stages of truth and knowledge. Following the rules is foundational to Sufi spirituality.

According to Suleyman, you cannot pick and choose who you listen to and which rules you will follow. When the rules from different sources of authority conflict, it is the duty of the faithful to try and make them work together as best as possible. You can draw from the Quran, Islamic Scholars, government guidelines, and Allah himself when trying to arrive at the best compromise, but the rules must be followed.

Suleyman made it clear why following the rules, all the rules, is so important, especially in a time of pandemic. “All life is sacred. You have to save a life! So, by not coming to worship, it’s not something you choose or you like. Because God says life is sacred, we have to save it. You save lives by respecting the restrictions the authorities put in place.”

Still, there is an element of worship that cannot be captured at home, and no amount of justifying why a rule was put in place can overcome the sense of loss that follows. Zoom meetings are fine for passing a sermon, and the musical poetry of the Qasidas can be found on any platform that allows audio uploads. It’s ok – but it cannot capture the power of a zikar meditation in the dark, surrounded by the voices of other practitioners. You cannot pass the warmth of a shared meal through a screen as easily as you could a plate of food to a person beside you. Worship is about community, and the digital realm can only take you so far into the spiritual realm.

The Most Distinguished Naqshbandi Sufi Order had to abandon in-person worship in March of 2020, just like most other houses of worship around the United States. . Despite the yearning for their shared community, the members dutifully stayed apart for 15 months until the authorities told them they could return. They masked and sanitized as they were told, and refrained from shaking hands, an important part of establishing a connection to each other. Now, nine months later, they were able to worship with few restrictions. They could even share a meal again.

Speaking privately, Suleyman explained why he didn’t mind the lack of physical connection at first. “If you wear a nice perfume, and I sit near you for one hour, what happens? I will smell like it! When we sit together, the goodness is like a contagious disease. It jumps from one person to another person.” His measured and steady voice did not waiver as he made the analogy, but the barest hint of wry smile crossed his face as he let the comparison sink in before moving on. “One good person in the room means the whole group gains from that individual.”

As restrictions begin to ease in New York, the Sufis allow themselves to become closer physically and spiritually once more. Whether the rules change again or the path ahead becomes unclear, they know to accept and obey what they are told. For now, they revel in the spread of the spirit while the spread of COVID dies down.

During COVID-19, a Gurdwara in Queens Informs and Feeds

Like houses of worship all around New York City, the Sikh temple on 97th avenue in Queens was closed in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was no service, no washing, no head covering, no offerings.

But one element of the Sikh temple continued.

The gurdwara’s kitchen stayed open to serve meals to the city’s essential workers and members of the Black Lives Matter movement. At a time when many people did not have access to meals, the kitchen was open 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Such a kitchen operation, run by Sikh volunteers, is known as langar.

Japneet Singh, a Sikh activist and community member of District 28 in Queens, estimates that 100,000 meals were distributed from March 2020 to March 2021.

In Fall 2020, the congregation resumed prayer within the halls of the temple, known as a gurdwara, but with a new accessory: masks. They were largely hesitant to participate in langar so instead bowed in the Darbar Sahib prayer hall and left—forgoing an integral part of the faith’s routine.

Their skepticism came from evidence. In January 2021, the Richmond Hill section of Queens had one of the highest COVID-19 positivity rates across the city. This rate lingered. The community saw spiked rates because it is made up of an immigrant population with a large proportion of essential workers.

Singh, who ran for City Council in 2021, lost the primary election. Democratic opponent, Adrienne Adams, resumed her incumbency. According to Singh, no one from the city government came to the gurdwara to inform the community or train them on the health protocols to undertake during this time. Pamphlets were provided by the city but were not translated for the community that understands Punjabi, Hindi or Urdu, he said. Community members took to using the gurdwara as a site for distributing personal protective equipment such as masks and hand sanitizer.

The neighborhood was without a vaccine or testing facility until community leaders advocated for them. When they were unable to get them from the city, they reached out to third parties. Mobile vaccination vans, also offering testing, were set up outside the gurdwara in 2021.

Today, as COVID-19 positivity rates stabilize across the city, the vaccine vans are a less common sight. On Sundays, the day when Sikhs are off from work and find the time to worship en masse, they walk past a desk in the corner of the gurdwara, where two city employees sit, offering COVID resources like literature for the community.

Worshipers today will also notice a small, black webcam propped tall on a stand before the priests. The Sikh Cultural Society has over 7,500 followers on its Facebook page and uploads its prayer sessions to the page. The page’s photo gallery is also packed with images displaying the day’s holy scripture, hukam.

These technological innovations were started prior to the pandemic, at the suggestion of the head Granthi, or ceremonial protector of the Sikh holy book, to meet the needs of the community. At one point, WhatsApp Messenger, which is popular among the South Asian community, was used to deliver the daily hukam, but Facebook provides a larger reach.

Today, Singh, who is running for election in State Senate District 17, notices more food pantries popping up across the city. He recalls the efforts he witnessed from his community and is hopeful about the next stage.

“Humanity is a beautiful thing,” he said. “We can climb out of the hardest of hard.”

A Renewed Connection on the Upper West Side

Every Sunday since the pandemic began Hope West Side hosts two services. The evangelical Christian congregation rents the sanctuary of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism on West 86th Street and Central Park West. Inside you won’t see a cross, but you will see Jewish symbols in the colorful stained-glass windows. Under every seat are Shabbat prayer books instead of Christian Bibles. Hope West Side is a newer congregation, only founded in 2018. Because the Society for the Advancement of Judaism holds its services on Saturdays, it allows Hope West Side to have the space on Sundays. When the pandemic hit, though, the building went dark and both the Jewish and the Christian congregations were homeless.

The services went online, starting out with pre-recorded live streams and moving on to Zoom meetings, but some of those involved with the church felt this deprived them of a sense of community within the church. Christina Jackson serves as the communications director and tries to engage members during the year of virtual worship.

“I think it’s hard because part of the reason why I come to church at least is for the community,” Jackson said. “We tried our best to have the chat box going on the YouTube Live Stream and reach out to people we were already connected with, but for new people, it was really hard.”

Finally, last June, after 14 months, the church was able to hold services in person, while also streaming to the web, but not without challenges. The church had to purchase and set up cameras, WIFI and projectors. In the back of the worship space a large camera manned by volunteers captures the worship music, the sermon and then the worship music again, but of course it misses the connection between worshipers before and after the services. Those who did attend in person, didn’t fully get that connection either.

The Society for the Advancement of Judaism lowered the number of people permitted in the building at any given time, to ensure proper social distancing requirements were met. Hope West Side switched from holding one service, as they did before the pandemic, to two services. This way, half of the churchgoers would attend each one, with around 30 at each. This worked for a while, but once the Society for the Advancement of Judaism lifted that restriction, Pastor Mike Park enthusiastically announced that the congregation would return to one service. This announcement was met with cheers from the churchgoers.

“I realize there’s a couple things that we’ve lost in having two services,” Park said. “We are never in the same room together.”

On February 27th, Hope West Side held their first in-person singular service since the beginning of March 2020. Nearly every seat was filled, with around 70 people in attendance, all wearing the name tags given to them at the door when they completed their Covid-19 screenings. Before and after the service people laughed and talked. They poured and sipped on coffee provided in the lobby. This 11 AM service represented a return to normalcy after nearly two years navigating Covid-safe services.

Along with this return, came the announcement of the first church retreat in two years. Taylor Fagins is the community life coordinator at the church and was excited to inform everyone of the trip upstate.

“It’s gonna be amazing, and I say that because I planned it,” he said to the congregation with an enthusiastic smile. This was met with laughter. “There’s gonna be hiking, board games, there might be some karaoke.”

Still, the church does take precautions to keep everyone safe, such as required masking and then health screenings at the door. They look forward to a time when they won’t have to do these things anymore.

“Maybe somewhere down the line we can unmask,” said Christina Jackson. “I think we are just playing it by ear and just doing what the whole city is doing: trying to keep everyone safe.”