From the streets to the sanctuary

From the streets to the sanctuary

Kayla Steinberg

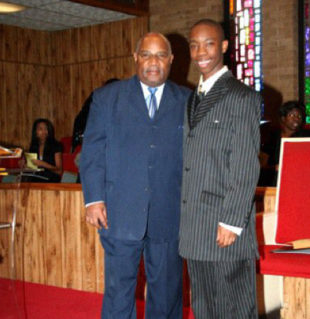

Don Abram was something of a prodigy growing up in his church in Chicago. As a 14-year-old in an oversized pinstripe suit, Abram preached from the pulpit of the Greater New Mount Eagle Missionary Baptist Church for the first time. When he finished, the crowd was on its feet.

But after he publicly came out as queer, Abram, 27, said he lost speaking invitations from pastors. One person even revoked an invitation.

Abram said the pastors offered seemingly innocuous excuses, like scheduling conflicts. But he thinks they silently were uncomfortable with his expression of his sexuality. “They just don’t say the quiet part out loud,” said Abram.

Elements of the Black church certainly have a problem with individuals who identify as LGBTQ+. But after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a white Minneapolis policeman and the nationwide protest movement that resulted, Abram believed there was an opportunity to help his community.

“I saw a renewed interest among the Black church to start having conversations around intersectional justice,” he said. “I thought that it was an opportune time for the Black church to recommit itself to freedom, liberation and justice for all of God’s children, including LGBTQ+ folks.”

So, Abram took to the streets.

He trekked to protests across Chicago, feet hurting, carrying a cardboard sign that read, in black letters, “SILENCE IS VIOLENCE.”

Abram refused to be silent. It was his spiritual beliefs — his belief in human dignity, a belief that all of us are children of God — that brought him to protest.

“It’s not just a cis, straight Black man who needs to be advocated for,” said Abram, who earned his Master’s of Divinity at Harvard but was never ordained by a church. “It’s also women, it’s also queer folk, it’s also differently abled folks.”

He wanted to make an effort to include them in a space he knows well: the Black church.

In March, Abram launched Pride in the Pews, an organization dedicated to the inclusion of LGBTQ+ people in the Black church. For its “Can I Get a Witness” project, Pride in the Pews is collecting 66 stories of queer Christians in the Black church, corresponding to the 66 books of the Bible. Abram hopes those stories will inspire change.

And change might be happening elsewhere. Earlier this month, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the largest Black Methodist denominations in the world, voted to create a committee that will study LGBTQ+ matters.

Dr. Teresa Fry Brown, the fourteenth historiographer of the AME Church, said the church has been discussing LGBTQ+ issues on-and-off for a number of years. Now that the AME General Conference passed the resolution, church leaders will look deeply into them.

The committee will study texts that discuss sexuality, hear testimonials from Black LGBTQ+ people within and outside the AME Church and propose legislation addressing the rights of LGBTQ+ people in the AME Church, all by the church’s 2024 General Conference. Abram and Dr. Jennifer Leath, a co-author of the resolution and the pastor of Campbell Chapel AME Church in Denver, spoke about a possible collaboration for the testimonials, though nothing is set just yet.

Leath, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, sees encouraging conversation about how the church views LGBTQ+ individuals as a “defense of my own dignity.” And, she said, “there are many, many others who are like me.”

The typical Black church stance toward LGBTQ+ people has been “don’t ask, don’t tell,” said Ronald Hopson, a professor of psychology and pastoral care at Howard Divinity School who teaches about sexuality and the Black church. Of course, he added, LGBTQ+ individuals have always been in the church.

“There’s a kind of anecdotal lore that the Black church would not have music without gay men,” he said.

But being gay has historically been considered a sin, said Hopson. At some churches, those who are openly LGBTQ+ could be ostracized or asked not to participate in a church role. Some LGBTQ+ church leaders might alternatively seek forgiveness from the church and ask to be allowed to continue in their leadership roles. Other LGBTQ+ church leaders might leave altogether, like the late writer James Baldwin, who ministered as a teenager.

Hopson attributes change to Black women in theological education, womanists (who see society and the world through Black women’s experiences) and young people who he said “have not been socialized with the same prejudices and bigotry that two generations of earlier people were raised with.” He considers BLM to be part of this larger, preexisting effort to create change.

The Rev. Vanessa M. Brown also credits young people with shifting the conversation in the church. The pastor and founder of Rivers of Living Water UCC, an LGBTQ+ affirming, “radically inclusive” congregation in the Upper West Side and in Newark, New Jersey, said before the Black Lives Matter movement was born, churches saw an exodus of young congregants who did not want to be part of an institution that wasn’t more inclusive.

“I don’t think Black Lives Matter is driving change,” she said. “It is young people who are helping churches to see that if you can’t open up, if you can’t really be inclusive, then I don’t want to be here.”

Brown, 50, knew she liked girls at around 12 but still married a man. She’ll never forget a conversation with her dad on her wedding day. “My own father said to me, ‘You look beautiful, but you don't look happy,’” said Brown.

She worried about what others would think of her and how it would reflect on her church if she walked away, if she left her fiancé at the altar. So she didn’t. Amid the divorce, which came just months later, Brown decided to leave the church.

But her friends encouraged her to start her own.

“The more you exclude, the more you run people away,” said Brown. “And people are looking for inclusive places to be themselves, whatever that looks like for them.”

But Rivers of Living Water is an exception. Many Black churches today, like Ebenezer Gospel Tabernacle in Harlem, do not fully affirm LGBTQ+ people. That’s a stance they attribute to several Bible passages, like Leviticus 20:13. “If a man lies with a male as with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination; they shall be put to death, their blood is upon them,” the verse reads.

The Harlem church welcomes everyone in prayer but not in leadership, said Jonathan Springer, a minister.

“If you’re preaching or teaching or in a position of authority, and you’re not living a lifestyle that’s consistent with the word, you have to go through a period of reconciliation or you have to step to the side,” Springer, 32, said.

Black Lives Matter has not changed Ebenezer Gospel Tabernacle’s stance on LGBTQ+ issues.

“I don't think that Black Lives Matter has influenced our church to think more reflectively from a theological perspective or from a sociological perspective about LGBT rights,” said Springer.

Hopson interprets Bible passages on sexuality differently. Considering the Hebrew, he said, can make the Leviticus verse about what distinguishes Jews and non-Jews rather than about homosexuality as an abomination. Hopson said some pastors understand that the verse doesn’t necessarily pertain to homosexuality but thinks they don’t want to disrupt harmony in their churches.

Abram hopes to create change on a larger scale — not through the Bible but through a different set of stories, those collected in Pride in the Pews’ “Can I Get a Witness” project. He imagines congregants will sit and listen to the wisdom from the stories, learn from them and create change.

“The same way that those texts and stories teach us about God and how we should relate to one another, the stories of queer and trans folks will teach us about God and how we should relate to one another,” said Abram. “Because our stories are sacred, too.”

Abram said he never believed homosexuality was bad though he recognized there was shame associated with it. He said he had tried to embody a sort of toxic masculinity. But it was more to secure his safety, he said, than because he believed being queer was problematic.

As time passed, he wanted to stand up for the LGBTQ+ community. Abram said so many people can’t be fully who they are because they have internalized anti-LGBTQ+ theologies. “For me, that is not what God has called us to do,” he said. “It is not the life that God wants for us.”