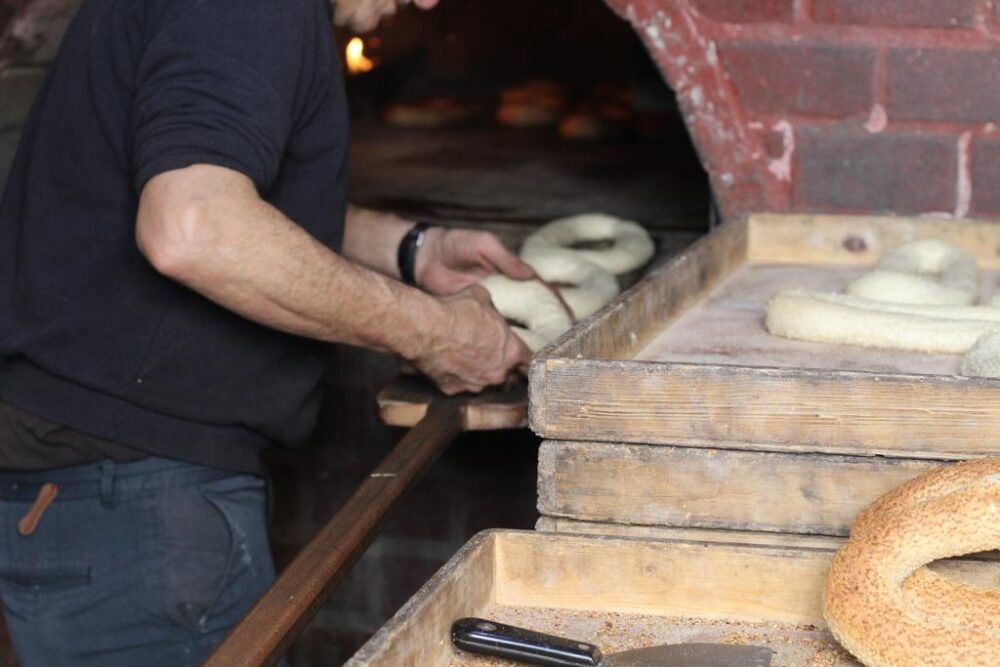

On Friday, we met tour guide Saleem Anfous, who took us through the Old City of Bethlehem. Our first task was to taste it. We stopped by a bakery for ka’ak al-Quds, a bread covered in sesame seeds that’s also called the “Jerusalem bagel.”

The bakery owner estimated that his traditional wood-fired oven, passed down by many generations of his ancestors, is anywhere from 700 to 800 years old. We got a bag of ka’ak bread fresh out of that oven to share. We split the freshly-baked, oval-shaped bread into four pieces per person. I opened up my piece, releasing the steam, and sandwiched falafel into its center.

Anfous described the city of Bethlehem, with its population of 33,000, as “tiny” and close-knit. Indeed, throughout the tour, our guide was greeted by friends and family on the street. So was Adjunct Professor Greg Khalil, whose family is from nearby Beit Sahour.

Anfous approximates that within the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Jerusalem, there are five million Palestinians (with Palestinian ID). Of that population, 40,000 are Christians. They’re a minority, but they punch above their weight.

Anfous cited Palestinian Christians’ contributions to the larger community. “We’re the salt of the community,” Anfous said, saying a small sprinkle of salt in one’s food is enough to get its flavor just right.

After sharing the story of Christ’s birth, Anfous delved into the history of the Church of the Nativity. Not only is it considered the oldest church in the world, it is also the holiest site for Christians.

In 70 AD, following the destruction of the city of Jerusalem, Christians gravitated towards a new superlative holy place: Jesus’s birthplace. Roman Emperor Hadrian ordered the building of the Temple of Venus, the Temple of Jupiter and the Holy Sepulchre — as a mockery towards Christianity, they were built on top of their house of worship. It wound up becoming a boon for the Chrstian faith as it allowed the church to remain preserved. Two hundred years later, the Roman Empire itself became Christian.

Unlike holy sites of so many other empires, this church has successfully avoided destruction. When we entered, we saw bits of the original floor, a remnant of the original Byzantine church that was built here in 335. High up on the wall were more mosaics, some of which were only recently uncovered.

Inside the adjoining Church of St. Catherine, signs were plastered along the walls that read “SILENCE.” Clergy and security staff roamed about to enforce the policy. Despite this, whispers abounded. When the choir began to sing “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” a hush fell over the crowd. The walls reverberated as their voices echoed throughout the chamber. It was eerie, yet beautiful.

We hopped on the bus to make our way to our next destination: the Tent of Nations, an educational, collaborative Palestinian farm. After crossing the muddy threshold, we walked the dirt path leading to the site. The view of the hill was breathtaking — but in the foreground, trash was strewn along the sides of the path.

We gathered in Meladeh’s Cave at the behest of its director Daoud Nassar. The cave was cozy yet accommodating enough for our entire group. Along the walls were vibrant paintings of orange human figures against a bright blue background, sprinkled with quotes in dozens of languages. One read: “Peace, justice and conservation of the creation.”

Nassar’s family has owned this farm for more than 100 years — since the time of the Ottoman Empire. Despite such a storied history, his family has had more than its fair share of legal struggles to validate their claim to their own land. Beginning in 1967, the Israeli government required them to register their land in order to pay property taxes — a tough ask for a community built on the principle of handshake agreements as opposed to documentation.

Nassar said he’s been involved in a legal battle over the land with the Israeli government for more than three decades.

But he hasn’t lost hope. In fact, that’s what his farm means to him. The planting of slow-growing olive trees represents the time investment and community effort required to maintain the land. The hands painted on the door represent people joining together to create something beautiful.

“Although the way for justice seems too long, too difficult, too complicated,” Nassar said, “we believe that one day justice will prevail.”

Our muddy and well-fed group piled back onto Lillian, our trusted bus, who carried us to Jerusalem, where we would spend our last two nights. In the late afternoon, as we approached Shabbat, we trekked to the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, for a tour.

Shelly Eshkoli, our tour guide for the afternoon, corralled the group into a small alley for a moment away from the crowds. “The hardest thing to find in the Old City is a quiet spot,” she said, as a passing car honked and we scurried out of its path.

Apart from leading nerve-fraying tours, Eshkoli is a biblical researcher, specializing in the women of the Old Testament — who she said have been “erased.” We all know Moses, she noted, but do we know the name of his wife? (Incidentally, one of my classmates did, but that is beside the point.) As we walked through the cobblestoned streets, polished from the footsteps of pilgrims and tourists, she explained how the city came to be divided into Christian Muslim and Jewish quarters: People lived everywhere but tended to concentrate close to religious sites that were important to their faith.

Eshkoli later stopped outside a small, stone-brick building, and pointed at a glass case affixed to the outside of the house. The Hanukkah candles were originally displayed on the window so that everyone could see the physical manifestation of the Jewish miracle. As she was explaining this, a man wearing all white (kippah and beard included), entered a kabbalistic synagogue, his pristine dress attracting curious glances within the group. For Shabbat, she explained, men dress in white shirts — the best of the best.

Fashion, in general, was a topic of curiosity on Friday. Some Ashkenazi Jews we saw were dressed in long, golden robes, unlike the black and white dress of the majority. This trend began hundreds of years ago, when the Ultra-Orthodox were first moving into the Jordanian-occupied territory and were living alongside Arabs.

Eshkoli explained that because they were quite poor, they began building their synagogue using loans from the Arabs, which they later defaulted on. In order to trick the lenders, who had come to mistrust them, they began dressing like rich Assyrians to emulate wealth.

We next visited the Western Wall, where we were reminded of a phrase Professor Ari Goldman used earlier in the trip — “holy envy” — meaning a wish to participate in another faith’s rituals.

Peeking out of the crevices of the wall were pieces of paper, on which visitors write wishes or prayers to converse with God. Eshkoll, however, told us she believed just thinking the prayer in the presence of the wall was enough.

At the wall, student Kelly Waldron said she felt “holy FOMO” (for the uninitiated, that’s “fear of missing out”) on the apparent catharsis experienced by the people surrounding us.

The sun was setting, and the air was charged by the hums, prayers and song of this congregation from all over the world. Wishes that had broken free scattered across the ground, like the suds of a wave in a sea of shuffling feet trying to make it to shore. As our group made its way to the exit, we could hear the Muslim call to prayer.