In Anxious Times, Asian Columbia Students Turn to Buddhism

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Ling Lan was thrilled when she was accepted into the highly competitive Ph.D. program in mathematics at Columbia University in 2019. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York with a vengeance. Lan’s funding was suddenly in question and she had to find a new professor who could fund her before the deadline to ensure her study.

Lan, who is 24 years old and is from China, was so anxious. The immediate lockdown made it far more difficult for her to get in touch with potential funders. She could only send cold emails to professors and might not get any responses for a long time. She was so worried; she couldn’t fall asleep at night.

As a long-time Buddhist, Lan decided to turn to the Buddhist practice of meditation to calm and release her anxieties.

“Meditation allows me to focus on the difficulty itself, without any negative emotion that might affect my thinking,” Lan said. “I sit for an incense every day, and at night I can sleep well, for I don’t have to bring too many concerns into bed.”

Lan is not the only young student who turned to Buddhism to seek emotional support. Statistics show that Buddhism is quickly gaining popularity among younger people, especially well-educated college students. According to the Pew Research Center, from 2007 to 2014, in the U.S., the Buddhists' population between 18 to 29 years old increased by 11%, from 23% to 34%, being the fastest among all age groups they’ve researched. In China, a study by Peking University points out that Buddhism has more believers under 40 years old, and tends to attract more well-educated people than other religions.

At Columbia, the Zen Buddhism Club has more than 30 students from different backgrounds who speak Mandarin. Lan serves as the founder of the club. Once every two weeks, the members gather on Zoom for a discussion under the guidance of a Buddhist teacher named Master Jiantan.

Jiantan fully converted to Buddhism a few years after finishing his Ph.D. degree at Taiwan University Department of Electrical Engineering. He became a monk at ChungTai Zen Center, one of the biggest Buddhism temples in Taiwan, and then moved to Houston, Texas to operate an affiliate. “Jiantan” is his Dharma name after he became a monk. The name means “see ephemera” in Chinese. In Buddhism, believers should all call one by his/her Dharma name after he/she got one from a monk or a temple.

He and Lan met at NYU’s Zen Buddhism club. After a few lectures, Lan followed Jiantan and went to the 7-Day Meditation event he held at his temple in Houston. The event is so focused on meditation that the faithful who gather do not speak a word or use their phones, even when they were eating and going to bed at night.

When Jiantan started to advise the Columbia Zen Buddhism Club, he gave lectures on Dharma (Buddhism rules and philosophies). However, the leaders found that the members were not as interested as they thought they would be. Therefore, Lan and Jiantan decided to change to those topics that related closely to student’s daily life, like how to deal with peer pressure, anxiety, procrastination, or why chose to go vegetarian, and analyze it from a Buddhism perspective. Since lots of members are female, Lan also designed special topics for them about appearance and body anxiety.

Jiantan, around his 40s, teaches differently here and in his temple in Houston. Compared to Columbia, believers in Houston are around 50 to 60 and has more experiences and more “results” in their life. Usually, he teaches them how to find reasons behind their already-existed “unsatisfaction” and “suffering.” At Columbia, Jiantan encourages young people to use Buddhist techniques like meditation to help them achieve success, both in academics and careers.

“We changed the topics to make it compatible with student’s life,” Jiantan said, “it’s a starting point that brings students to the town hall of Buddhism, so when they are facing challenges, they can use the principles of Dharma to deal with it, instead of having negative emotions or feeling depressed and hesitant.”

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Besides academic and career life, young Buddhists are also exploring topics around dating and romance. Kuang Huang, 27, is one of the initial members of the club. At the beginning of the New York City lockdown, his love life fell into trouble. He didn’t tell anyone. However, one day after a regular lecture in the Buddhism club, Jiantan asked Huang how he felt about people's unhappy love life. Huang still doesn’t know how Jiantan found out about his trouble. “Probably through some of my expressions,” Huang said. “But when I actually spoke out my confusion and opinion [to another person], I felt relieved.”

To Huang, Buddhism not only taught him how to heal from a broken love relationship but also enabled him to actively strengthen his bond with his family. And that’s the main reason that prompted him to study Buddhism in the first place. Huang’s mother is a lay Buddhist in China. Initially, Huang thought Buddhism was just a way she uses to kill time and meet new people after retirement. She would go to temples and events near her home, chant with the monks there, and told her experience to Huang.

At first, Huang didn’t know what to say when she told him about her exciting new Buddhism experience. But after he started to learn Buddhism with Master Jiantan, he better understood his mother’s faith and practice. Their mother-son relationship improved. “We would talk about the books that Master Jiantan referred to during the lecture, and she would tell me what Buddhism book she was reading, and recommend them to me,” Huang said. “It’s a spiritual activity for her.”

Both Lan and Huang said the most popular topic in the Columbia club has been the negative circle of procrastination and anxiety. There were many questions for Jiantan after his lecture on that topic. Lan said she felt procrastination and anxiety were problems that everyone was facing now. “It’s not that kind of anxiety about your career or life plan for the next two years,” Lan said. “It’s happening now.”

Before the pandemic and lockdowns in New York, the club members would gather at school once a week, watching Jiantan’s live lecture on the big screen together in a classroom, meditate and chant with him. After the lecture, the club members would stick around for a while, share snacks and talking to each other. The club would also hold dumplings-making events during the Chinese spring festival.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

However, soon after the club’s event schedule got stable, the pandemic began. For the past year, members can only attend the lectures from their own homes through zoom meetings. But still, though physically distanced, the similar problem, choices, and ethnicity of its members made the club a “safe zone” for Chinese international students. It is a place where they have the chance to speak a familiar language, and address their confusion to a familiar crowd. “I feel a sense of involvement when we all have the same confusion,” Lan said. “We are a group. And then when Master Jiantan started to lecture on it, we would have a better understanding of what he said.”

At the end of each lecture, Jiantan leads students in a meditation. “Meditation helped to relieve our worries [towards our safety]”, Huang said referring to the recent spate of anti-Asian hate crimes. He explained that “the heart of compassion” is important for Buddhists, and protecting oneself is actually saving others, for “you won’t give others the chance to hurt you and thus do evil,” Huang said.

Lan noted that her fellow Columbia students have different concerns than their parents back in China. The older generation might wish for a stable life, for they’ve been through starving or social turbulence. While the younger Buddhists usually have a better material life, they might live with bigger mental pressure.

“Each generation has its own characteristics when studying Buddhism due to the era they grew up in,” Lan said.

But in Buddhism, their final destination might be the same.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

The Meaning of Purim, the Jewish Identity

On Saturday evening, the Orthodox Jewish community of the Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun gathers in the Synagogue to close Shabbat with a Havdalah blessing.

Halfway through the service, one rabbi gives a pre-printed source sheet to each synagogue member. Rachel Kraus leaves her seat in the women's section and steps to the front of the synagogue audience. She cautiously removes her face mask to make her voice echo throughout the room as she adjusts her long dress and begins the sermon.

She encourages the faithful to use the 30 days between now and Purim to reflect on the nuances of the holiday. Purim is the 15th day of Adar and is a holiday for Jews to be happy. According to the book of Esther, in the 5th century BCE, the Jews survived after the Persian rulers ordered to kill them, and Purim was the day when they celebrated their salvation.

Kraus vigorously explains to the congregation her interpretation of Purim and what this holiday indicates about Jewish identity. To do so, she uses 13 texts that are listed on the source sheet.

"Just as with the beginning of Av, rejoicings are curtailed, so with the beginning of Adar rejoicings are increased" (Talmud Masechet Ta'anit 29a). This is the first source in Kraus' collection. She explains to the congregation that Purim contrasts with the month of Av, which represents disruption and is seen as the lowest and saddest time in Judaism. Both temples in Jerusalem were destroyed during this month, and other calamities struck the Jews.

On the contrary, Purim is a happy and festive day. However, Kraus mentions that there are phrases and passages in the biblical and historical Jewish texts where this day does not seem so happy. The question, then, is whether Purim is a joyful day or not. Kraus answers that it is both, and it is a moment when we need to take a deep look inside ourselves.

According to Kraus, one must use the month of Av as a counterpoint to make the best of the day of Purim and be happy. The believer is called upon to understand whether they are giving attention to the right things or taking the wrong path. She says that this idea also defines Jewish identity as a community that always looks to its past to know how to face the future; "These days of Purim shall never be repealed among the Jews, and the memory of them shall never cease from their descendants." (Esther 9:28) Jews must always have their entire journey in mind. "(Purim) Help us go in the right direction," says Kraus.

The congregation listens in respectful silence to Kraus' words. Everyone is seated with their gazes turned toward her. This is one of the only moments when no one speaks or prays simultaneously, as it sometimes happens during the intonation of the hymns.

Even the children who usually do not actively follow the evening services are now sitting and listening to the young woman's words in front of the congregation, who encourage the faithful to reflect. There are about 50 men and a dozen women in the synagogue, and they all follow closely, nodding when they recognize themselves in Klaus' explanations of the Talmud.

Kraus ends her sermon; Purim is not just a happy holiday. It is a day when the faithful reflect on their past to make the right choices in the future. "When we forget where we come, we forget where we go," she recalls.

The congregation thanks Kraus by saying "Shabbat Shalom," and she returns to the midst of the women, who greet her with congratulations.

The faithful pass around the Havdalah spice box, and each member of the congregation sniffs it to give themselves energies for the next week until the following Shabbat. The rabbi blows out the candles. The service is over, and with it, the Shabbat.

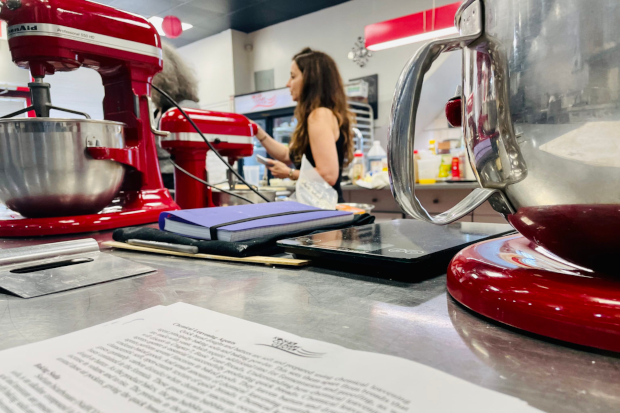

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Emma’s Torch: Religion and Food

Kathleen Shriver

Some of the best views of New York’s Statue of Liberty are from a waterside park in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood. From there, visitors can see the broken shackles at Lady Liberty’s feet, the golden fire raging from her copper torch, and the words to “The New Colossus,” the sonnet at her pedestal.

Just a few blocks from New York’s Statue of Liberty, a nonprofit restaurant and school labors to keep the spirit of Lady Liberty alive. It is known as Emma’s Torch, a tribute to Emma Lazarus, the Jewish American poet whose verse -- “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe” – decorates Liberty’s pedestal. Founded by Kerry Brodie, Emma’s Torch aims to empower refugees, asylum seekers, and survivors of human trafficking through culinary education.

When launching the nonprofit, 27 year old Brodie, thought back to her highschool -- Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School -- where she learned about Jewish leaders. She says Lazarus was one of the “unsung female heroes of Jewish history” whose work always stuck with her.

“I felt like Emma never got to see what her poem would become,” Brodie said. “ So my hope is that Emma's Torch will also be able to create that sort of lasting legacy and those ripple effects of change as well.”

In the Jewish tradition, when speaking of a righteous deceased person, many will say Z"l (pronounced zal), which is an abbreviation for Zikronam L'bracha. This literally means “may their memory be for a blessing.” “I think this definitely applies to how we are trying to honor Emma's legacy and memory. We are working in her memory,” Brodie says.

While for many restaurants, reopening after the pandemic means staffing up, adding tables, expanding menus, opening the doors earlier and closing them later, for Brodie, it means reprioritizing. It means reconsidering the purpose of Emma’s Torch and drawing from her past and, as it turns out, her faith.

Since its founding in 2017, Emma’s Torch has become a beacon of hope for hundreds. The nonprofit offers a full-time paid training program, during which students receive instruction, mentorship, and work experience, while also developing English conversation skills and other “soft skills” such as resume development and computer literacy.

In 2020, Brodie was looking forward to formalizing and publishing her curriculum and opening new locations around the country.

“2020 was supposed to be the year of stability,” she said. Instead, she got a global pandemic, an economic crisis, and a racial reckoning.

While the pandemic threatened the lives and livelihoods of everyone, the toll it took on those working in the restaurant industry was especially dire. To make matters even worse, Emma’s Torch doubled as a training program for immigrant communities, some of the country’s most vulnerable. Even so, Brodie had faith.

Brodie’s Jewish faith has gotten her family through a profoundly difficult past. “My great grandparents are among the only people from their families, to survive the Holocaust,” she said.

She recalled that several years ago she joined her grandfather on a trip to Lithuania, where many members of his family were murdered by the Nazis. “Standing there was just such an eye-opening experience of what happens when we don't remember that our neighbors are not that different to us, and that's just always stuck with me,” she said.

Ever since this experience, Brodie has been particularly motivated by the Jewish practice of welcoming the stranger. A commandment that is repeated 36 times in the Torah, the scripture reminds Jews that they once “were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 19:33-34). “We hope to live up to this commandment and imperative in our work.” At the same time, Brodie doesn’t see these values as exclusive to Judaism.

She loves learning from her students how these same values can come from different life experiences, including other religious traditions.

“At Emma’s Torch, a lot of times either our students come from very strong backgrounds of faith, or are supported and have found friends through their religious community, whether that be a church or a synagogue or mosque,” she said. “Faith in general can be such a powerful tool to bring people together.”

These universal values of unity and welcome have motivated every step of Brodie’s career. After graduating from Princeton University with a degree in Near and Middle Eastern Studies, Brodie hoped to effect change through public policy.

Following two years of policy work at the Israeli Embassy in Washington DC, she became the press secretary for the Human Rights Campaign, a nongovernmental agency based in Washington D.C., where she publicized the organization’s international work. At the same time, she spent her free time meeting with women who inspired her next endeavor.

“I started volunteering at a homeless shelter and was really struck by the conversations about food that I would have with the women at the shelter,” she said.

Brodie wanted to cook with the women. She grew up learning to cook different dishes that connected her to her family’s religious and cultural history and inspired her pride in that history. She wanted to find a way to use food to do more than just feed these women. She wanted food to empower them, too.

“Recipes are not simply a list of ingredients. Each is wrapped in memories,” she said. “Cooking simultaneously defines and transcends our communities.”

Growing up, Brodie would visit her grandparents in South Africa, where they had found refuge during World War II. Both of Brodie’s parents were raised in South Africa and her grandparents still live there today. And during her earliest visits to her grandparents, Brodie learned to cook.

“My grandmother makes the most incredible milchika which are basically South African cinnamon buns. One of my earliest cooking memories is helping her make these.” While many American Jews have foods like bagels-and-lox to break their fasts on the Jewish High Holidays, South African Jews break their fast with milchika–a kind of cinnamon bun. Dishes like milkchika and the religious traditions around sharing them with family and friends has always inspired Brodie to see food as a powerful element in strengthening her faith and in enforcing a shared sense of identity amongst her community of faith.

For this reason, she encourages her students to embrace and celebrate their origins and home countries when they cook.

“Food helps our students understand that they’re not victims and that their work is valuable,” she says. Brodie says that she wants her students to see that each of their unique understandings of flavor and culture can actually enhance our communities and inspire our kitchens.

Inspired by her love of food and her conversations with the women at the homeless shelter, Brodie started reading about the restaurant industry. She read about widening labor gaps and about restaurants struggling to find talent to build out their kitchens.In May of 2016, Brodie left the HRC and began studying at the Institute of Culinary Education.

When she wasn’t learning to cook, Brodie was working to build out the organization of her dreams: a restaurant that would provide opportunities for the most vulnerable, a restaurant that would tell stories through its food.

She wanted to provide jobs for those who were left out. She wanted to bring people of different backgrounds and life experiences together in a space that felt comfortable to all of them; in a space where they could connect and realize that they could, in fact, work together. That space was the kitchen. And after graduating from culinary school in June of 2017, Brodie launched her first pilot program at Emma’s Torch.

Emma’s Torch began offering a free 12-week apprenticeship program with up to 500 hours of culinary and professional training. What’s more, students were paid to participate, allowing them to train full-time and cover expenses.

By the end of 2019, over 100 students had graduated from the program with professional culinary skills, English proficiency, and a community of support. Ninety-seven percent of the graduates had been placed in culinary jobs around the city.

And then, the pandemic hit. Like most people working in the hospitality industry in New York, many alumni were laid off or furloughed and Brodie was forced to close her training program and restaurant. She closed the doors of her restaurant and sent her students and staff home. But Brodie didn’t give up.

She turned her faith into action. The organization remained stable due to support from donors and a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Meanwhile, the Emma’s Torch staff began volunteering to work with students and alumni online. They hosted online cooking classes while also helping students and alumni apply for unemployment benefits. And Brodie innovated, working with old and new partners on her “Culinary Council” to restructure the business in response to the shifting industry.

After six months of solely online programming, Emma’s Torch reopened in October of 2020 with a three track program including the original culinary program in addition to two new tracks for alumni: the first being a community building program and the second a management-level leadership development fellowship for select program graduates.

Ruslan Abdraimov, a graduate of Emma’s Torch, participated in the fellowship. Abdraimov arrived in New York from Russia in 2016 with just $216 in his pocket and no understanding of the English language. Fleeing cultural and political persecution, he left everyone and everything he knew behind – for a chance to start over in America.

He knew one person in New York, who loaned him his sofa and told him about Emma’s Torch. Abdrainmov applied to the pilot program in 2017 and became a student in the first graduating cohort at Emma’s Torch.

Abdraimov remembers making 12 dishes on his graduation night. “I can’t choose a favorite,” he laughs. “It’s like asking [me] to pick [a] favorite child.”

But four of the dishes made him especially proud – a combination he calls “Winter’s Heat.” The roasted buckwheat katah, celery potato mash, sauerkraut stir fried with German sausage, and deep fried mushroom stuffed meatballs use all the vegetables available during winters in Russia. “Winters in a large part of Russia are long and cold. And you have to eat a lot to keep yourself warm,” he says with a smile.

Abdraimov describes his experience at Emma’s Torch as more than just an education in the culinary arts.“You know, it’s one thing when you hear about different countries and religions, but the other thing is, when you actually have a chance to meet that person and spend some time in a kitchen with that person, you know, and be around them every day, like for eight to 10 hours a day,” he said, nodding his head. “You learn a lot. And behind all that history, it’s something universal -- things like kindness, friendship.”

As Brodie shifts her focus to the students and alumni, the flames of Lady Liberty’s fire continue to burn at Emma’s Torch, which has transformed into a take-out cafe. As it was before the pandemic, the menu remains “New American cuisine,” cooked by New Americans.

‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

As published in the Columbia News Service

‘Not Your Mother’s Potato Latkes’

Lily Lopate

Kosher cooking has a lot of rules, but that doesn’t mean that learning kosher cooking isn’t fun. During a pastry workshop at the Kosher Culinary Center in Brooklyn in July, the students — six women, one teenage boy and one man — were tasting bite-sized cocoa pear muffins that had just emerged from the oven. “These muffins are perfect for a ladies’ brunch, bridal shower or bris,” said Avram Wiseman, 64, the Center’s co-founder and chef. As the class inspected the flecks of melted chocolate and grated pears, the teenage student looked despondently at a muffin that overflowed in the baking tray. Wiseman noticed. “What do we do with our mistakes?” he asked. “We eat them!”

There’s plenty of humor at the Kosher Culinary Center, especially since it reopened to full capacity cooking classes this summer. Located in Sheepshead Bay, between Marine Park and Mill Basin, the center offers recreational cooking classes, a catering business and a professional culinary training program.

Because people experience faith at varying degrees, the center’s aim is inclusivity, and its students make up an eclectic mix of Orthodox, Conservative and Reconstructionist Jews. “We cater to everyone regardless of how religious they are,” said the center’s director and co-founder, Perline Dayan, 53. “One does not need to have knowledge of kashrut laws prior to starting our program.”

This attempt to create common ground, through food, among segments of the Jewish population that may otherwise be isolated from each other has made the center a place for members of the Jewish Brooklyn community to connect or reconnect. Recreational and professional classes are open to men and women, ages 16 and older. And things are getting busy again now that in-person gatherings are less restricted than they were last summer. “Once people got vaccinated, our class size shot up,” said Dayan.

The increased number of students has inspired the school to apply for full accreditation, which would grant it an added degree of recognition as an educational institution. It’s currently the only trade school licensed by the state of New York to teach the skills needed to work in the kosher food industry.

In addition to its classes, the center’s also seen an increase of customers who book the venue for social events. People come for Jewish Singles Night or Culinary Date Night. “The date nights always fill up fast,” said Dayan. “A few couples meet for the first time and make a signature cocktail, kalamata olive focaccia and the chef’s choice of hors d’oeuvres.” The center has also resumed catering for large party events up to 50 people, a significant increase from the 10-person average last summer.

The center certainly has the look of a place where serious cooking happens. In the airy, industrial-sized teaching kitchen are red cupboards filled with baking tools, large pieces of cookware hang from a pot rack that wraps around the ceiling and students wearing black aprons work at long silver tables. A Star of David and printouts of Hebrew prayers are taped to the entryway wall. Opposite the sink, a framed plaque displays the kosher certification signed by two rabbis from the Northern American Kosher Supervision. If it weren’t for these hints of Judaism, the Kosher Culinary Center — which founders say is the only school outside of Israel to offer professional training in the kosher culinary arts — looks just like any professional cooking school.

Wiseman’s classes are the most popular, said Dayan. “Students love him,” she said. It is easy to see why: his sense of humor and playfulness in the kitchen allows him to quote apt lessons from the Torah as he’s teaching. In a class on “quick dry breads,” Wiseman asked, “What is the origin of unleavened bread?” And when students answered “Passover,” he explained further. “When Pharoah agreed to let the Israelites go, they hurried out of Egypt. They were in such a hurry they could not let their bread rise all the way so they took it with them just as it was starting to rise. So, there you go — quick bread.”

Wiseman teaches classes in both the professional and recreational tracks. Recreational classes are shorter and focus on one theme, like breads, desserts or meats. Professional classes are much more intensive. They include 216 hours (or 54 days) of hands-on training in technical professional skills and techniques. Courses last 11-16 weeks, and participants must enter with a high school diploma or equivalent degree to obtain a certificate from the culinary program. Students are drilled on how to cook safely and skillfully in a kosher environment, and the course’s difficulty escalates from knife skills to breads, starches, stocks, fish and meat.

The school also provides counseling, networking opportunities and interview preps to help students make the transition into a full-time culinary job. Come the end of the term, students in the professional classes must take a final exam to test their knowledge of kosher rules.

Before co-founding the center with Dayan in 2015, Wiseman had been teaching for several years, most recently at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts in Brooklyn, which closed in November 2015. He had also worked in a variety of settings, including the United Nations, where he was the executive sous chef. In that role, he said, “I cooked for several presidents: Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon. Each one had their quirky favorites.” He also cooked there for Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen.

Though he keeps kosher, Wiseman’s years in the culinary industry were spent cooking in non-kosher kitchens at a large, restaurant scale. His vast career network allows him to connect students with colleagues in the industry. “I’m doing this so people can gain a parnassah [the tools to make a decent living],” Wiseman said. It’s a way of passing on the trade through generations.

Dayan met Wiseman when she took a class of his in 2013 at the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts. “It opened up a whole new world. I had never tasted a beet before,” she said. Dayan, like many of Wiseman’s students, is a career switcher. After years working in the trading firm Ladenburg Thalmann and Co., she wanted a change.When the Center for Kosher Culinary Arts was forced to close because it was operating without a license, Wiseman and Dayan decided to form a partnership. “I come from accounting and he’s a professional chef,” she said. “We decided to start our own school.”

Their vision was to create a modern twist on kosher cooking. “We do traditional Jewish foods, but we do them with style,” said Wiseman. “It’s not your mother’s potato latkes. We make it gourmet.” To stay relevant, they also teach a range of global cuisines including French, Italian, Vietnamese and Greek. Recently, at the request of one student, Sephardic dishes were added such as cassola (sweet cheese pancakes), buñuelos (puffed fritters with an orange glaze), keftes de espinaka (spinach patties), and keftes de prasa (leek patties).

For Dayan, an observant Jew, the kosher component was critical to the partnership. “If it wasn’t going to be a kosher school then I wouldn’t be here,” she said. To be fully compliant as “kashrut” (kosher), the kitchen must be supervised by a rabbi, and a certified “mashgiach” (the kitchen supervisor), must always be present. The kashrut rules are strict and unyielding: no meat can coexist with dairy in the kitchen and even meat and dairy utensils must be separated. Recently, a younger student entered class with a Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and, when asked whether it contained milk, was directed to go outside and immediately throw it away. It is common practice to toss out or “tear” food that is out of order. (The Yiddish word “treif” derives from the Hebrew word for torn).

Across the spectrum of Judaism, the level of piety in the kitchen may vary. A nostalgic relationship to Jewish cuisine is sometimes described derisively as “Kitchen Judaism,” referring to Jews for whom religion revolves mainly around food. At the center, the connection between faith and food is clearer. “There’s more to Judaism than just being Jewish and cooking at the same time,” said Dayan. “So, if we have someone who is new to Judaism, we educate them on aspects of the religion.”

But regardless of the degree of piety, once students come to the center, they are part of the “whole mishpachah” (family) as Leah Waronker, a recent high school graduate and volunteer at the center, described it. “To cook kosher is to have faith in Judaism,” she said. “There’s a real intimacy that comes from working inside this community. From the moment I first put on my apron, I was welcomed with warmth. I literally fell in love.”

Back in the kitchen classroom, the smell of baked apple and cinnamon fills the room as the students begin preparing country-style biscuits. “Gentlemen,” Wiseman said to the two males in the class, “when you’re working with the flaky dough, bring out your feminine side. Be tender.” If the dough lacks moistness, he recommended more kosher butter (a non-dairy substance akin to margarine). “We grab the block of frozen butter, and we grate it like mozzarella cheese into the bowl. Now, we add vanilla. Say it with me,” he said, waving a wooden spoon like a conductor. The class recited the words after him “van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a, van-i-ll-a.”

For Alla Dorch, an architect and student in the pastry class, baking kosher started as a peripheral activity and is now central to her life. “Cooking is usually something I do on the way to doing something else, you know?” she said. “I have my own design studio, so this started as something I could do with my family. But now I realize the crossover with architecture and pastry — both are very precise.” As Dorch’s interest in kosher culinary arts has grown, she is now considering starting a baking business. “It’s funny,” she said. “I used to go to synagogue to think about what comes next in my life. Now I come here.”

“The Whole Situation was Soaked in Love”

“The Whole Situation was Soaked in Love”

Lucy Soucek

When Hope Fried first received the text from her staff chaplain, she burst into tears. Pacing her Manhattan apartment, her mind was racing. It was spring of 2021 and she was working the on-call shift of her chaplaincy residency at nearby Mt. Sinai hospital. The message came in at around nine in the evening explaining that a mother in the labor and delivery unit was preparing to give birth to a baby either stillborn or expected to pass away soon after birth. The mother was Roman Catholic, Spanish speaking, and she was asking for her child to be baptized.

Fried, 32, is Jewish. Normally, she would have called for a Catholic priest to conduct the baptism, but this was during the overnight shift. If the baby was born alive and they waited for the priest to make it over to the hospital, they ran the risk that the baby might die before the priest arrived.

Fried wasn’t allowed at the hospital during the overnight shift because of Covid restrictions. She had never been to a Catholic baptism, and now she would have to talk a doctor or a nurse through one from her living room on the phone in Spanish in the middle of the night during a pandemic. After her initial bout of panic, she realized that she had a choice to make. And that choice was experienced by many chaplains over the past year and a half.

“COVID made it so that in the times where you would call for a priest or you'd try to call for an Imam, that wasn't available,” said Fried. “So it asked more of us because just the logistics weren't really possible. I think a lot of chaplains were like, okay, we just have to show up with our full humanity.”

In hospitals across New York City, pandemic restrictions have forced chaplains to navigate novel and potentially uncomfortable situations in their attempts to administer care. But what has guided them through the last year and a half is training that prepares them to honor the belief systems of their patients, even when those belief systems are dramatically different from their own. Now, chaplains and chaplain educators are focusing on how to care for themselves so that they can care for others as they continue to practice both in person and remotely.

For Fried, growing up in a multi-religious household influenced her eventual path to chaplaincy. Her mom is Catholic and her dad is Jewish. Ever since she was young, she’s felt more connected to Judaism, although she’s never had a strong belief in God. That’s where her humanism comes in. She identifies as a Jewish Humanist, which means she is ethnically Jewish, but in terms of spiritual beliefs, she doesn’t believe in a higher power.

When deciding what she wanted to pursue in her career, religion felt important. She thought, if she was meant to become a rabbi, God would reach out. But that just never happened. And so she turned to chaplaincy. It was a way for her to still feel connected with her faith, despite not believing in a higher power, and it allowed her to just sit with people and help them navigate hardships.

“I thought, ‘maybe I should try chaplaincy,’” said Fried. “It doesn't have to be super religious, but you get to be with people; you get to accompany people.”

She attended Union Theological Seminary, graduating in the spring of 2020. After taking four units of Clinical Pastoral Education to become board certified and participating in a yearlong residency. She is now a staff chaplain at the Hospital for Special Surgery in Manhattan.

It was during her residency that she navigated the baptism. And so on that night, Fried spoke with the doctor, who also happens to be Jewish, and they decided to make it happen. “We were both very firm,” Fried said. “I remember that feeling of being really grounded in our intention of like, we've been asked to do this; we are going to do this.”

After they made the decision, it was all about talking through logistics. Fried’s staff chaplain and clinical supervisor emailed her a guide to performing an emergency baptism, with details outlining the protocol, sample prayers and information on how to provide support over the phone.

She didn’t know Spanish, so she pulled up YouTube videos and practiced it with her husband over and over again, then walked the doctor through the ritual instructions on the phone. The doctor would need a little pill cup of sterilized water, which would act as holy water. Typically, holy water is water that has been blessed by a member of the clergy, but in the hospital, the protocol is different.

Dabble water on the baby’s forehead, and say:

“[Patient’s name,] Bautizo a ti en el nombre del Padre,” [I baptize you in the name of the Father].

Drop of water.

“y del Hijo.” [and the Son].

Drop of water.

“Y del Espiritu Santo,” [and the Holy Spirit].

Drop of water.

“Amen.”

The baby was born at around 4:30am, alive. A nurse performed the baptism, though Fried doesn’t know their personal religion or language preference. And then, at 4:45am, Fried called the on-call priest to come to the hospital to bless the baby and provide an official document. The baby survived for a couple of hours and then died later that morning.

In the Catholic church, baptism is seen as a way to cleanse infants from the original sin they were born with, and to welcome them into the Catholic faith. So Fried says the family was deeply appreciative that they were able to perform the ritual and receive the certificate.

“I think sometimes we attend to the worst moments in people's lives,” said Fried. “We try to be present and accompany and we try to lessen, slightly, their spiritual distress, and I think having their baby baptized was able to slightly lessen some of that spiritual distress.”

Throughout this whole situation was the tension between Fried’s Jewish Humanism and the Catholic ritual that she was being asked to lead someone through. But Fried, relying on what she learned about being a hospital chaplain where they often have to navigate interfaith situations, thinks of it as an expression of love.

“If a family has this request and this is their ultimate expression of love and will provide some sense of spiritual relief to know that their baby has been baptized and blessed by God and will be accepted into heaven, I think that's an ultimate expression of love and I will perform it,” said Fried.

Hospital chaplains navigate these complicated situations every day, but many also benefit from a system of training called Clinical Pastoral Education that is in place to guide them. During her yearlong residency, Fried was guided by her education supervisor, Rev. David Fleenor. He is the director of education for the Center for Spirituality and Health and the Assistant Professor of Medical Education at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai. He is also ordained as an Episcopal priest.

One idea that Fleenor, 46, taught Fried to keep at the forefront of her mind was to think about the context of the situation and how that determines her role as the chaplain. For Fried, the pandemic, the timing of the birth, the support she received from educators and other chaplains, and the importance of this ritual to the family all drove her decision to make sure it would happen.

“The whole situation was soaked in love,” Fleenor said. “People have their own convictions, but the beautiful work that she did was to dig deeper within herself and find that love was a deeper value; that love and care and compassion compelled her more to facilitate this meaningful ritual for this family, at such a profound time of loss in their life.”

Profound loss was ubiquitous throughout the pandemic. And hospital chaplains spent much of their time caring for not only patients and families, but staff as well. At Mount Sinai, chaplains had the option to administer care throughout the pandemic in person, and many did. Fleenor said their role of caring for staff at the hospital was vital and is too valuable for the field to be replaced by services done over the phone.

“What happens with chaplains is that they are embedded on units and they walk around and staff informally say, ‘Man I'm really struggling,’” said Fleenor. “They're not necessarily gonna reach out to the employee assistance program. But when the chaplain happens to be there, then they open up.”

But to be able to provide staff support, hospital chaplains also need to know how to take care of themselves.

At Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the staff chaplains were able to administer care in person throughout the pandemic, just not in the rooms of COVID-19 patients. Figuring out how to sustain care and avoid compassion fatigue is now one of their primary concerns.

“It’s like everyone's taking a vacation or is sick or something,” said Rev. Christine Davies, ordained Presbyterian minister and the director of pastoral care at Robert Wood Johnson. “They're all dropping like flies just because of the sheer amount of suffering that they witnessed; It’s unparalleled. And so I think they’re still carrying a lot of that.”

Davies, 38, teaches Clinical Pastoral Care Education courses as well, and she says that much of what she teaches her students has to do with learning how to maintain their own emotional wellbeing so that they can care for others. Especially after this past year.

“Even right now, when we're not in a surge, I'm cognizant of my students’ cumulative exhaustion since the pandemic started,” said Davies. “A lot of it is helping them to see and acknowledge and be aware of their own feelings and emotions so that they can honor the emotions in others.”

For Fried, practicing chaplaincy during the pandemic will stay with her for a long time, and she’s learned to recognize when she might not be able to give the care she wishes she could. “I think it just really made me aware of how long lasting the intensity of the pain that we're asked to witness and hold is, and that that can become sort of ingrained in your body and needs to be processed over a longer period of time,” Fried said.

When she got home from her shift the day after the baptism, her husband ordered her favorite takeout dish, Pad Thai, and she spent the afternoon watching The Real Housewives and taking moments to cry. Fleenor and she have a running joke that she’s the crying chaplain.

“Your body needs to release the anguish and the fear and uncertainty,” Fried said. “All that needs to come out, and my way is through crying.”