In Anxious Times, Asian Columbia Students Turn to Buddhism

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Ling Lan was thrilled when she was accepted into the highly competitive Ph.D. program in mathematics at Columbia University in 2019. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York with a vengeance. Lan’s funding was suddenly in question and she had to find a new professor who could fund her before the deadline to ensure her study.

Lan, who is 24 years old and is from China, was so anxious. The immediate lockdown made it far more difficult for her to get in touch with potential funders. She could only send cold emails to professors and might not get any responses for a long time. She was so worried; she couldn’t fall asleep at night.

As a long-time Buddhist, Lan decided to turn to the Buddhist practice of meditation to calm and release her anxieties.

“Meditation allows me to focus on the difficulty itself, without any negative emotion that might affect my thinking,” Lan said. “I sit for an incense every day, and at night I can sleep well, for I don’t have to bring too many concerns into bed.”

Lan is not the only young student who turned to Buddhism to seek emotional support. Statistics show that Buddhism is quickly gaining popularity among younger people, especially well-educated college students. According to the Pew Research Center, from 2007 to 2014, in the U.S., the Buddhists' population between 18 to 29 years old increased by 11%, from 23% to 34%, being the fastest among all age groups they’ve researched. In China, a study by Peking University points out that Buddhism has more believers under 40 years old, and tends to attract more well-educated people than other religions.

At Columbia, the Zen Buddhism Club has more than 30 students from different backgrounds who speak Mandarin. Lan serves as the founder of the club. Once every two weeks, the members gather on Zoom for a discussion under the guidance of a Buddhist teacher named Master Jiantan.

Jiantan fully converted to Buddhism a few years after finishing his Ph.D. degree at Taiwan University Department of Electrical Engineering. He became a monk at ChungTai Zen Center, one of the biggest Buddhism temples in Taiwan, and then moved to Houston, Texas to operate an affiliate. “Jiantan” is his Dharma name after he became a monk. The name means “see ephemera” in Chinese. In Buddhism, believers should all call one by his/her Dharma name after he/she got one from a monk or a temple.

He and Lan met at NYU’s Zen Buddhism club. After a few lectures, Lan followed Jiantan and went to the 7-Day Meditation event he held at his temple in Houston. The event is so focused on meditation that the faithful who gather do not speak a word or use their phones, even when they were eating and going to bed at night.

When Jiantan started to advise the Columbia Zen Buddhism Club, he gave lectures on Dharma (Buddhism rules and philosophies). However, the leaders found that the members were not as interested as they thought they would be. Therefore, Lan and Jiantan decided to change to those topics that related closely to student’s daily life, like how to deal with peer pressure, anxiety, procrastination, or why chose to go vegetarian, and analyze it from a Buddhism perspective. Since lots of members are female, Lan also designed special topics for them about appearance and body anxiety.

Jiantan, around his 40s, teaches differently here and in his temple in Houston. Compared to Columbia, believers in Houston are around 50 to 60 and has more experiences and more “results” in their life. Usually, he teaches them how to find reasons behind their already-existed “unsatisfaction” and “suffering.” At Columbia, Jiantan encourages young people to use Buddhist techniques like meditation to help them achieve success, both in academics and careers.

“We changed the topics to make it compatible with student’s life,” Jiantan said, “it’s a starting point that brings students to the town hall of Buddhism, so when they are facing challenges, they can use the principles of Dharma to deal with it, instead of having negative emotions or feeling depressed and hesitant.”

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Besides academic and career life, young Buddhists are also exploring topics around dating and romance. Kuang Huang, 27, is one of the initial members of the club. At the beginning of the New York City lockdown, his love life fell into trouble. He didn’t tell anyone. However, one day after a regular lecture in the Buddhism club, Jiantan asked Huang how he felt about people's unhappy love life. Huang still doesn’t know how Jiantan found out about his trouble. “Probably through some of my expressions,” Huang said. “But when I actually spoke out my confusion and opinion [to another person], I felt relieved.”

To Huang, Buddhism not only taught him how to heal from a broken love relationship but also enabled him to actively strengthen his bond with his family. And that’s the main reason that prompted him to study Buddhism in the first place. Huang’s mother is a lay Buddhist in China. Initially, Huang thought Buddhism was just a way she uses to kill time and meet new people after retirement. She would go to temples and events near her home, chant with the monks there, and told her experience to Huang.

At first, Huang didn’t know what to say when she told him about her exciting new Buddhism experience. But after he started to learn Buddhism with Master Jiantan, he better understood his mother’s faith and practice. Their mother-son relationship improved. “We would talk about the books that Master Jiantan referred to during the lecture, and she would tell me what Buddhism book she was reading, and recommend them to me,” Huang said. “It’s a spiritual activity for her.”

Both Lan and Huang said the most popular topic in the Columbia club has been the negative circle of procrastination and anxiety. There were many questions for Jiantan after his lecture on that topic. Lan said she felt procrastination and anxiety were problems that everyone was facing now. “It’s not that kind of anxiety about your career or life plan for the next two years,” Lan said. “It’s happening now.”

Before the pandemic and lockdowns in New York, the club members would gather at school once a week, watching Jiantan’s live lecture on the big screen together in a classroom, meditate and chant with him. After the lecture, the club members would stick around for a while, share snacks and talking to each other. The club would also hold dumplings-making events during the Chinese spring festival.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

However, soon after the club’s event schedule got stable, the pandemic began. For the past year, members can only attend the lectures from their own homes through zoom meetings. But still, though physically distanced, the similar problem, choices, and ethnicity of its members made the club a “safe zone” for Chinese international students. It is a place where they have the chance to speak a familiar language, and address their confusion to a familiar crowd. “I feel a sense of involvement when we all have the same confusion,” Lan said. “We are a group. And then when Master Jiantan started to lecture on it, we would have a better understanding of what he said.”

At the end of each lecture, Jiantan leads students in a meditation. “Meditation helped to relieve our worries [towards our safety]”, Huang said referring to the recent spate of anti-Asian hate crimes. He explained that “the heart of compassion” is important for Buddhists, and protecting oneself is actually saving others, for “you won’t give others the chance to hurt you and thus do evil,” Huang said.

Lan noted that her fellow Columbia students have different concerns than their parents back in China. The older generation might wish for a stable life, for they’ve been through starving or social turbulence. While the younger Buddhists usually have a better material life, they might live with bigger mental pressure.

“Each generation has its own characteristics when studying Buddhism due to the era they grew up in,” Lan said.

But in Buddhism, their final destination might be the same.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Palm Sunday on a Christian Commune

ULSTER PARK, N.Y. -- Founded in 1920’s Germany, the Bruderhof (translated to “place of brothers”) is an Anabaptist Christian movement. Among other faith principles, the Bruderhof movement emphasizes pacifism, common ownership, adult baptism and evangelism. The Bruderhof has 26 settlements all over the world - 17 of which are in the United States - and all are organized around the customs in a book written and published by members of the community, Foundations of Our Faith and Calling.

On Palm Sunday, our class's reporters spent the holiday among one of the Bruderhof’s larger settlements, listening to their members' stories and seeking to break down barriers and understand this century-old religious crusade.

Scroll through the photos below for a glimpse of the day.

All photos by Riley Farrell, April 22.

A New Buddhist Ritual: Chanting Online to Release the Souls of the Dead

A Buddhist passed away in New York City.

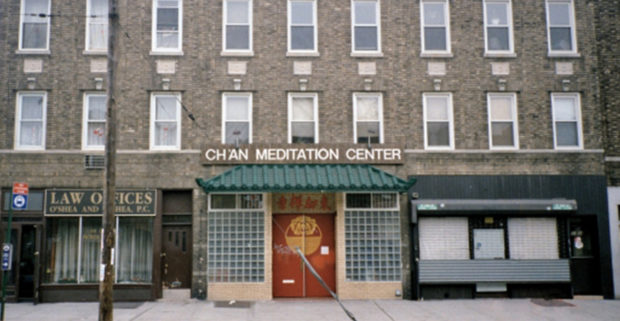

His funeral was two weeks ago. Only a limited number of family members were allowed at the scene because of the pandemic. Master Chang Xun and her “householders” from the Chen Meditation Center in Queens were unable to attend, so they decided to go online and chant with the family at the funeral service. Buddhists believe that the soul can be released from purgatory through religious changing.

The long-distance chanting at the funeral was only one way that the Chen Meditation Center, located at Corona Ave in Queens, has been coping with the pandemic that swept through the globe over the last two years.

Chan Meditation Center in Queens, New York City. Photo courtesy: Chan Meditation Center’s official website.

At first, the center, like many other houses of worship, closed its doors. It gradually resumed its regular activities by holding hybrid classes and services, both online and in-person. On Sunday evenings, about a dozen members gathered in their temporary “Bodhimaṇḍa”, a place of enlightenment for Buddhists to sit down and meditate, which usually has one or more Buddha statues in it to watch the 2020 movie “The Father”–and discussed it after the screening. The film, starring Anthony Hopkins, is about an aging man who must deal with his progressing dementia. Half of the members sat in a circle, talking, while others were busy preparing homemade marshmallow cookies beside the window. At the end of the hall, a golden statue of Buddha sat quietly, staring at people from on high. A robot vacuum wandered leisurely on the floor below his feet.

Chang Xun said that online classes have actually increased the center’s audience. “Around 70 to 80 people attend online classes and meditations,” Chang Xun said. “Comparing to 30 people in the old days when we were meeting in person.”

Ming Shi, a householder at the Chen Meditation Center, said that online Dharma classes allow her to listen to different Master’s classes from different places. “We invited Master Sheng Dian’s disciple in Europe to discuss Dharma this Sunday since there are no geographical restrictions online.”

However, Masters, householders, and other participants are all hoping the activities can soon resume in person, especially because of the lack of empathy when talking online. “We cannot see each other’s facial expression clearly”, said Chang Xun. She’s also concerned that online classes have a strict time limit of one hour, while they can go longer when meeting in person.

Shi, as one of the organizers of young Buddhists’ classes in the New York area, worried about how sincerely young Buddhists can learn from online classes and chanting: “I don’t feel elderly Buddhists affected by the online classes very much. Young people did. Because there are lots of distractions in your life. if you are physically going to the meditation center and learning with others, you don’t have the chance to do other things, but you might do other things simultaneously when learning online.”

Despite online classes, Master Chang Xun must also cope with the lack of volunteers in the center during the pandemic. Usually, some familiar participants and householders in the center served as volunteers to cook vegetarian meals, do cleanings, and organize events, but during the pandemic, some volunteers cannot come to the center very often. Chang Xun herself had to take all their jobs.

That wasn’t too bad until one day she had to go to the market.

Chang Xun, like many Buddhists, is a strict vegetarian. She accidentally walked through several meat stalls in the market to get to the stalls that sell vegetables. She smelt the odor of fish and meats, and can’t stop thinking about when they were still alive. “I almost cried,” She said. “I can’t stand their suffer.”

The day after she had come back from the market, Master Chang Xun still thought about these creatures, even when she was teaching Dharma classes. “I can still smell them,” she said. She made a special prayer for the livestock she encountered at the market.

Now, Chang Xun seemed not to have to struggle anymore. Volunteers are coming back these days as the positive cases in New York started decreasing. The center expects more volunteers to come back in the following month.

However, their coping moments never cease. To Buddhists, Dharma itself is the way that they are trying to cope with any new situation in their lives–Asian hate crime, diseases, kindness, wars… etc.—even though this situation seems to violate their belief.

The Meaning of Purim, the Jewish Identity

On Saturday evening, the Orthodox Jewish community of the Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun gathers in the Synagogue to close Shabbat with a Havdalah blessing.

Halfway through the service, one rabbi gives a pre-printed source sheet to each synagogue member. Rachel Kraus leaves her seat in the women's section and steps to the front of the synagogue audience. She cautiously removes her face mask to make her voice echo throughout the room as she adjusts her long dress and begins the sermon.

She encourages the faithful to use the 30 days between now and Purim to reflect on the nuances of the holiday. Purim is the 15th day of Adar and is a holiday for Jews to be happy. According to the book of Esther, in the 5th century BCE, the Jews survived after the Persian rulers ordered to kill them, and Purim was the day when they celebrated their salvation.

Kraus vigorously explains to the congregation her interpretation of Purim and what this holiday indicates about Jewish identity. To do so, she uses 13 texts that are listed on the source sheet.

"Just as with the beginning of Av, rejoicings are curtailed, so with the beginning of Adar rejoicings are increased" (Talmud Masechet Ta'anit 29a). This is the first source in Kraus' collection. She explains to the congregation that Purim contrasts with the month of Av, which represents disruption and is seen as the lowest and saddest time in Judaism. Both temples in Jerusalem were destroyed during this month, and other calamities struck the Jews.

On the contrary, Purim is a happy and festive day. However, Kraus mentions that there are phrases and passages in the biblical and historical Jewish texts where this day does not seem so happy. The question, then, is whether Purim is a joyful day or not. Kraus answers that it is both, and it is a moment when we need to take a deep look inside ourselves.

According to Kraus, one must use the month of Av as a counterpoint to make the best of the day of Purim and be happy. The believer is called upon to understand whether they are giving attention to the right things or taking the wrong path. She says that this idea also defines Jewish identity as a community that always looks to its past to know how to face the future; "These days of Purim shall never be repealed among the Jews, and the memory of them shall never cease from their descendants." (Esther 9:28) Jews must always have their entire journey in mind. "(Purim) Help us go in the right direction," says Kraus.

The congregation listens in respectful silence to Kraus' words. Everyone is seated with their gazes turned toward her. This is one of the only moments when no one speaks or prays simultaneously, as it sometimes happens during the intonation of the hymns.

Even the children who usually do not actively follow the evening services are now sitting and listening to the young woman's words in front of the congregation, who encourage the faithful to reflect. There are about 50 men and a dozen women in the synagogue, and they all follow closely, nodding when they recognize themselves in Klaus' explanations of the Talmud.

Kraus ends her sermon; Purim is not just a happy holiday. It is a day when the faithful reflect on their past to make the right choices in the future. "When we forget where we come, we forget where we go," she recalls.

The congregation thanks Kraus by saying "Shabbat Shalom," and she returns to the midst of the women, who greet her with congratulations.

The faithful pass around the Havdalah spice box, and each member of the congregation sniffs it to give themselves energies for the next week until the following Shabbat. The rabbi blows out the candles. The service is over, and with it, the Shabbat.

Shuckling In A Modern Orthodox Synagogue

I do not know what time it is when Cantor Chaim Dovid Berson begins to sing the Amidah, or Shemoneh Esreh, which is the central part of the Jewish prayer. It is a prayer recited three times a day - morning, afternoon and evening - in Orthodox Jewish communities.

On this Friday evening, I attend Ma'ariv, the Jewish service recited after the sunset. I am in the Orthodox Jewish synagogue of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, located at 125 E. 85th St. on the Upper Eastside of Manhattan. No cell phones or other electronic devices are allowed here; that's why I don't know what time it is. This is a sacred place where the faithful share a moment of prayer with the community, and I understand that cell phones would distract people from this purpose.

Men and women sit separately in the synagogue, and I join the few women present. It is the first time I have ever visited a synagogue and the first time I have ever attended a service. I look around. The men are dressed in a jacket and tie and wear the kippah, a brimless cap worn as a sign of respect. The women are elegantly dressed. The rabbi is in the center of the room on the bima, a raised platform. He chants and the rest of the congregation sometimes joins the intonation of the hymn.

When the prayer intensifies, and voices rise, the faithful begin to rock. The hands either go down the body or hold the prayer book; the feet are stuck to the ground. Some go back and forth, some go from side to side, and some make a deep bow at the end of the swaying motion. This movement is called “shuckling,” which comes from the Yiddish word that means "to shake." It is a profoundly private moment between the faithful and their prayer, and each person takes as much time as they need to make this movement.

While the faithful continue to shuckling, I observe them in silence. It almost seems like I can see the energy pouring out of their bodies and pervading them. Quickly, I realize that there is not a time when the worshippers are called to make that movement. The person begins to rock back and forth at their discretion, when they want to, and without needing someone to tell them to do so. Everything seems spontaneous and authentic.

Next to me, a girl named Mia is particularly focused in prayer as she moves her body back and forth, occasionally making a deep bow. At the end of the service, she tells me that that movement is her way of praying, and there is no precise explanation behind this gesture.

According to Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz, the swinging represents the total immersion of the believer's energy in prayer. He also jokingly tells me that it is a movement-related only to Jews, particularly Orthodox Jews, and that the Prophet Mohammed is said to have warned his adherents "not to do like Jews who move back and forth."

There is also another explanation of shuckling that can be found in the past, according to an article written in 2013 by Miriam Goldmann, curator of the Jewish Museum Berlin’s exhibition “The Whole Truth.” In the 12th century in Spain, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi reported that often the Torah was read by many men at the same time. To ensure that the process was quick, they developed this movement whereby they would bend forward to see the book and then quickly retract to make room for the faithful afterward.

However, the service is now over. I gather my things and present myself to the rabbis. Meanwhile, the community members greet each other by saying "Shabbat Shalom," which is an invitation to enjoy a blessed Shabbat. I greet everyone by thanking them, and as a response, I receive a warm "Shabbat Shalom, Eleonora.”