Day 2: From Mary’s Well, to a Church Halfway House to an Ahmadi Mosque

By Ania Gruszczynska and Nora Zaim-Sassi

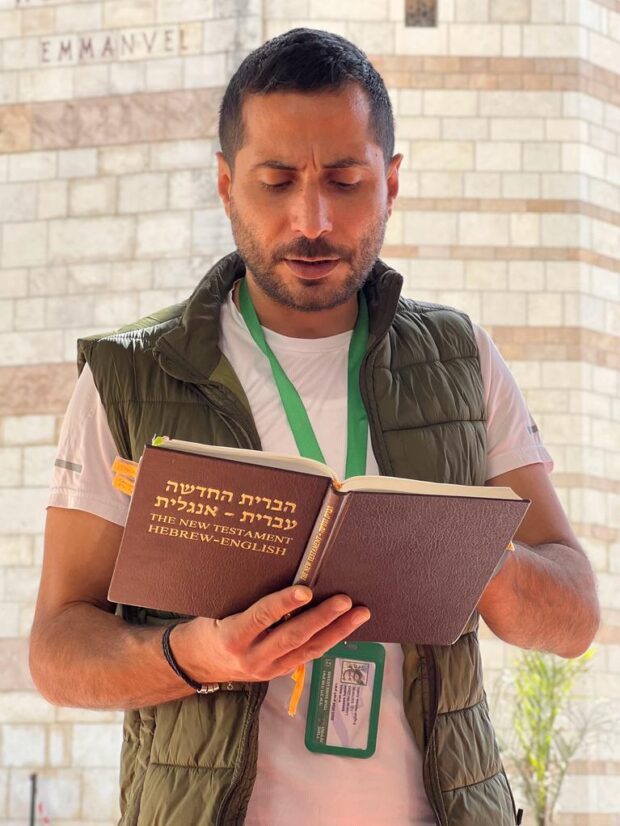

This morning, we met Bassam Hakim, our tour guide around Nazareth. Hakim grew up in the city in a family devoted to hospitality.

"Nazareth is my passion," he said, by way of introduction.

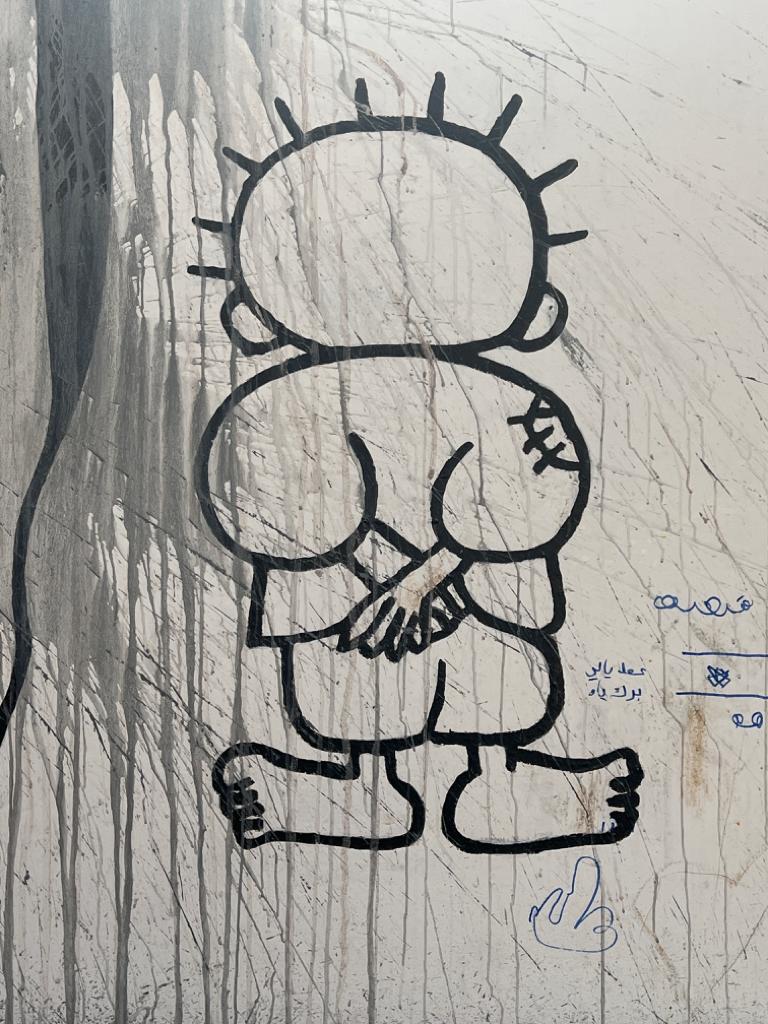

We made our first stop at Rehov Hagalil Street’s graffiti wall. Although Nazareth is in Israel, and everyone here is an Israeli citizen, the city is heavily Arab — 80% Muslim and 20% Christian — and support for the Palestinian cause is clear through the multitude of graffiti expressing solidarity for the struggle. One drawing says, "My homeland is not a bag, and I'm not traveling." The art is sometimes vandalized, but seems to always return, Hakim says. Another mural showed a little man turned away from the viewer, because he's always looking home. Hakim tells us this is a typical Palestinian symbol that is found throughout the Middle East.

Nazareth’s story centers on the Annunciation — the moment when Christians believe the Archangel Gabriel told a 13-year-old Jewish girl named Mary that she would give birth to God. We visited multiple religious sites in the city that claimed to be the site of this event.

One such site was Mary's Well. The original well was two sided, one for men and the other for women.

We then approached the Palestinian Orthodox Church of St. Gabriel, which also commemorates the Annunciation. The church was built in the form of a cross and split into two sections by a beautifully adorned iconostasis with scenes from both the New and Old Testaments. One side was dedicated to female saints, including Saint Barbara, an early Christian Lebanese martyr. At its furthest wing we looked into a water spring, still trickling, where Mary was said to have experienced the Annunciation. Coins lay on the bottom representing wishes and prayers.

We arrived at the Church of Annunciation. Monumental but stark, the structure was consecrated in 1969 and has been a Catholic site of worship ever since. Those countries who contributed the most to its erection are memorialized in a passage of Madonnas with Jesus, each visibly rooted in the local culture — Chinese, Brazilian, Polish or Ukrainian. We craned our necks to see a great geometric dome — a white lily representing purity, devotion and the Annunciation. Below it were two levels, the bottom one representing a fundamental darkness from which a Christian must emerge to enter light. The nave of the Basilica was the very cave that is believed to have held the New Testament scene. There is a marble altar illuminated in delicate blue light before which people pray. Letters on it spell: “Verbum Caro Hic Factum Est” — the word became flesh here.

As we walked through the city’s narrow streets, with mostly beige brick buildings, the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, hummed in the background. The call came from the White Mosque, the first mosque in Nazareth, constructed in 1805.

We traveled next to Haifa, a mixed Arab-Jewish town. We heard stories of coexistence and cooperation rarely found elsewhere in Israel, as well as stories of struggles and suffering.

Before 1948, Haifa had a population of 70,000 Arabs, but all but about 3,000 were expelled following the Arab-Israeli war, according to Jamal Shehade, the director of the House of Grace, a welcoming place for all regardless of religion, a rehabilitation center for prisoners, impoverished families and programs for children and elders.

Currently, the House of Grace houses 17 formerly incarcerated individuals in its rehabilitation program. Of these, 15 are Muslim, one is Druze and one is Christian. The House of Grace helps them find jobs, pay off debts and reintegrate into society.

As Easter, Passover and Ramadan approach, the House of Grace is preparing packaged meals of nonperishable food for 300 families throughout Haifa. Shehade, inspired by his father, who started this mission 40 years ago, serves and welcomes everyone into a space that does not discriminate, he said.

“This is not a missionary organization— we welcome anyone coming here asking for support as a human being.”

This theme of unification carried on into conversations with Imam Murad Odeh, Jamal Shehade’s friend and the Imam and General Secretary of the Ahmadiyya Shaykh Mahmud Mosque, which peers over the beach in the Kababair neighborhood of Haifa.

As we entered the congregation, a group of Jewish children headed out and Odeh greeted us. Odeh described his openness to all Jews, Christians and Muslims. He told us about a Jewish man wearing a kippah who prayed at the mosque. He told us — and anyone — “come and join me.” Odeh regularly leads interfaith discussions and panels with priests, rabbis, locals and foreigners.

We all silently entered the mosque, the women with their hair covered, with one man just wrapping up his prayer facing the center of the room, toward Mecca, with the Shahada in green Arabic script. Odeh passionately spoke about the importance of focus during prayer. “God warns people who come to pray without concentration,” he said.

He provided further insight during a conversation in his office, filled with books.

“Today all of us are suffering from wrong interpretations of holy scriptures,” he said. He continued to recite verses of the Quran and translate them into English, explaining interpretations that can lead to kindness, unity and altruism. Through this lens, he spoke highly of Haifa’s diversity and its residents' relatively successful coexistence.

“Haifa is the holiest city, in my perspective,” he said. “I think people make places holy — not the stones.”

Keep an eye out for Henrietta and Noelle’s post tomorrow about our trip to Bethlehem and Jericho!