BELFAST, Northern Ireland — Yousif Alshewaili, a 24-year-old Muslim who fled his native Iraq (pictured above), was recently granted asylum status in Northern Ireland. He is thankful for the reception he has received in his new country but says that it often comes with strings attached.

“People are super nice,” he said in a recent interview, but they also want to convert him to Christianity. “Some grandmas volunteer to teach English also through Jesus,” he said. They are constantly giving him Bibles.

“Like I had more Bibles than clothes, you know?” He chuckles as he recalls his early days there.

Alshewaili recounted an encounter where his reluctance to discard Bibles led to amusing exchanges. “One time I was asked by the hotel staff, ‘Yousif, are you religious?'” he recalled. “I was like, ‘No, it’s just that each time I go to the church, they give me a new Bible. I don’t want to be rude or throw them away.'”

Christians form an overwhelming majority of the population of Northern Ireland. When people there speak of religious diversity, they mean Catholics and Protestants. Northern Ireland is still deeply divided, largely coming from the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict that enhanced segregation between Catholics and Protestants and lasted for about 30 years from the 1960s to 1998.

Even today, the population predominantly identifies within these two groups. According to the 2021 census, 42% of the population identifies as Catholic, 30% as Protestant or other Christian denominations. Muslims like Alshewaili are a small minority. There are only about 12,000 Muslims in a country of just less than 2 million people, the census shows.

Despite efforts to foster inclusivity at the churches, religious undertones often remain — even in casual events.

“One of the churches that we go to after football, they offer us water and oranges and biscuits, coffee, you know, for free and they talk about Jesus,” Alshewaili shared. “They invite us to come to the prayers and stuff.”

During Ramadan, which ended this year on April 10, Alshewaili and his friends shared an iftar meal in South Belfast. This reunion for Ramadan was one of the few ways Alshewaili has managed to keep his roots and practice his religion — Islam — in a city that has made headlines for racism against religious minorities and for burning down places of worship for Muslims.

Alshewaili fled Iraq because of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) and fear of prosecution. Iraq had become intolerable, prompting him to leave the country. Since then, he has endured significant challenges in his life, including living in refugee camps in Greece and the UK. Despite these hardships, Alshewaili has managed to teach himself English and photography while living in a refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece, mastering both skills with remarkable proficiency.

Now, he lives in Belfast, works as a photographer, and is slowly building a new life in Northern Ireland, a place he has called home for the past one and a half years. He was also recently accepted for a program in cybersecurity engineering at a university in Derry.

When I arrived one night of Ramadan to interview Alshewaili at his friend’s house, I was immediately greeted with food. His friend offered me dates, a sweet fruit from the Middle East, and grape juice while we waited for the main meal. We shared the meal with three of his friends, two from Yemen, and another from Iraq, whom he had met in Bangor, Northern Ireland, when he lived in a hotel hosting asylum seekers. They all cooked dinner together while chatting in Arabic, with Alshewaili translating the conversation for me.

When one of his friends offered me grape juice, I thanked him.

“We don’t say ‘thank you’ and ‘sorry’ in Arabic,” he told me. “Because everything you do, you expect to come back to you. If you do good, good comes.”

Upon arriving in Northern Ireland, Alshewaili felt welcomed. However, he also faced the restrictions of living in a hotel used to host asylum seekers, such as not being allowed to work while waiting for his documentation, being prohibited from cooking, being prevented from leaving the hotel on Fridays and receiving only £8.86 in weekly cash support — enough only for a one-way train trip to see his lawyer.

“It’s just frustrating to seek asylum here because they don’t allow you to work until you get your asylum. So you’re basically living at the mercy of the government,” he said.

Constantly looking over his shoulder in Bangor, located a little less than an hour by train from Belfast, he lived in fear of potential attacks. The threat of violence loomed close, as many of his friends fell victim to street assaults in Bangor. Transitioning to Belfast offered a somewhat improved environment due to its larger size and more diverse population. However, even here, Alshewaili encountered troubling incidents. He recalls being followed while attending the gym, even to the changing rooms. One day, a staff member approached him, questioning his choice of footwear.

“At the end, she was like, ‘Look, if you don’t have trainers, we can donate. People donate them all the time for free,’” he said. “I was like. ‘What do you mean? Why would you say that?’ It’s racist. I came here to train, I pay for my membership. I have been a long-time member. So I don’t understand.”

“Peace walls” stand as stark reminders of the division between Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods in Northern Ireland. Some of these walls soar over 40 feet high, stretching approximately 21 miles (or 34 kilometers) in length. Initially erected during the Troubles to mitigate the risk of petrol bombs and missiles, these barriers are now more used for psychological security to both communities. To this day, many on the Protestant side identify strongly with the United Kingdom and British identity, while several members of the Catholic community align with Irish heritage.

Upon his arrival, Alshewaili was initially optimistic, believing that the people of Northern Ireland would empathize with his refugee past. “I thought I shared a lot of things in common with these people. They will understand me because they went through it all, so they will understand why I am here,” he expressed. “But unfortunately, only one side of the wall understands; the other side has been racist. Not everyone, but a lot.”

I asked Alshewaili to spend a day showing me Belfast from his perspective. As we navigated the city streets, the disparity between the communities became evident. While strolling through South and East Belfast, we observed strong loyalist sentiments depicted in murals.

We also passed areas where Arab businesses were burned down in allegedly racially motivated incidents. However, upon turning onto Northumberland Street and passing through the gates that segregate Protestant and Catholic areas, we noticed a palpable shift in the atmosphere, with signs welcoming immigrants and an Irish sentiment.

“One side is way more welcoming, way more nice,” he said. “Those who cared for refugees, most of them were from the Irish side of the wall. They were trying to fix the situation and organize a protest against this system. They tried to support us in any possible way.”

In 2021, the Belfast Multi-Cultural Association (BMCA) building, situated in South Belfast, a mainly Protestant Loyalist area, was destroyed by arson. BMCA is an association that fosters cultural diversity and community services such as a food bank and prayer area. The crime was believed to be motivated by hate, according to police reports. Just hours after repairs were completed in 2022, the building suffered another arson attack, further reinforcing suspicions of a hate crime. Faced with ongoing safety concerns, the BMCA decided to relocate to a different site in February 2023. Naomi Green of the Belfast Islamic Centre explained that BMCA has moved to another building in a more mixed area which is considered safer, and where a previous mosque was located for over 40 years without problem.

“For the previous area, I wouldn’t consider it a safe area for Muslims in particular, or people who may be ‘coded’ as Muslims — Arabs, South East Asians or African,” Green said. “No one was charged for most of the attacks in those areas.”

Despite these obstacles, Alshewaili acknowledged recent progress with advocacy for the creation of multicultural groups. “You know, it’s getting better,” he said. “Lots of people working on it and speaking on it.”

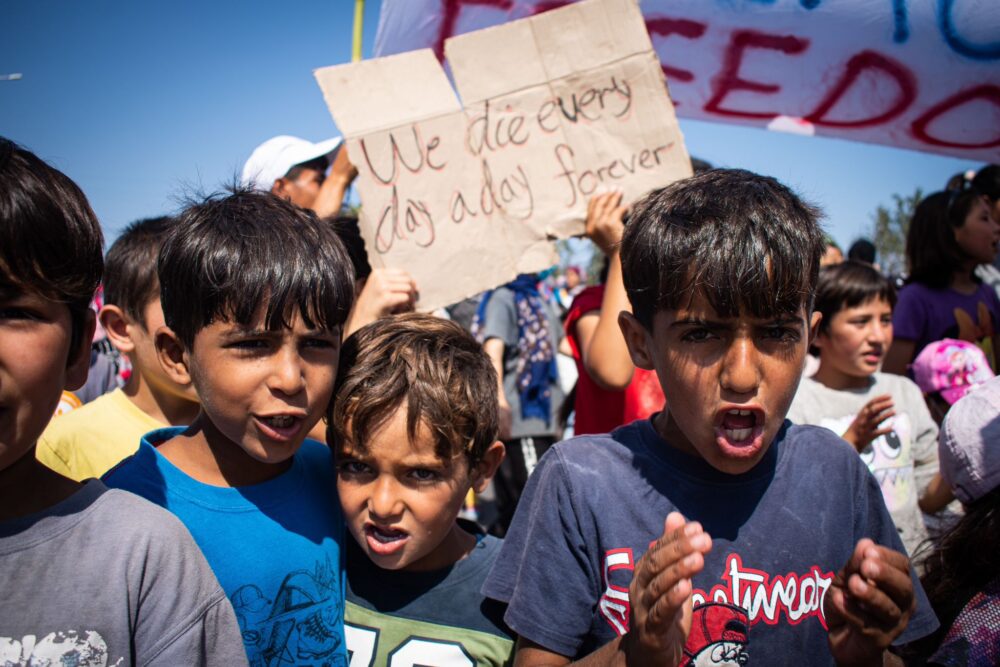

During his time in Bangor, Alshewaili believes he experienced his worst period yet. The region witnessed a surge of protests against immigrants residing in hotels, with demonstrators accusing them of various crimes and expressing discontent over government expenditure.

“Some people held different kinds of signs,” he said. “Signs accusing us of rape, theft, blaming the government for spending millions on us and labeling us as criminals, among other accusations.”

One notable example is the Facebook group “North Down Concerned Residents,” which attracted about 2,500 followers and serves as a platform for local opposition against refugees and asylum seekers. The group organizes protests outside hotels and voices grievances regarding the immigrant population in Northern Ireland.

Alshewaili perceived a deliberate attempt by the government to scapegoat refugees for economic woes. With private hotels housing immigrants paid for by the government, a large part of the Northern Ireland population is unsatisfied with the arrangement.

“The government is using refugees as scapegoats, telling them that the economy is bad because of refugees,” he said. “The asylum system in the UK is for profit. So they are profiting from me.”

A prior BBC investigation revealed that private companies are experiencing growing profits while the government spends millions of pounds daily to accommodate asylum seekers in the UK.

“Reducing the backlog in asylum cases and establishing a more efficient and robust decision-making system is not a strategy in and of itself to stop illegal migration but is important to taxpayer value and we have prioritised it,” said Minister for Immigration, Robert Jenrick, in a statement to the House of Commons on illegal migration.

There exists a suspicion that paramilitary groups may be orchestrating attacks against immigrants in Bangor. On one occasion, Alshewaili said the police had video footage of an incident but still did not get involved.

“We made two complaints about racism and racist attacks,” Alshewaili said. “They closed the investigation after two days only and told my friend that they could not identify the people. It is Bangor, it is not big. The police cannot act against the paramilitary.”

Alshewaili maintains that many of the tensions between the two communities could be alleviated through improved housing policies. “I would put more housing in Belfast for both communities,” he asserted. “Let everyone live with dignity.”