LONDONDERRY, Northern Ireland — Christine Cowley still remembers what it felt like to lose her first love. She was just 19 when the young man she loved, Colm Keenan, was killed by a British army patrol in this divided city. But for more than 50 years, she’s kept that part of her life secret.

“One of the hardest things in my life was coming to terms with this,” she said, tears filling her bright blue eyes.

It didn’t happen all at once. As Cowley got married and raised a family, she kept her secret buried deep inside. It wasn’t until after her children were grown that she began considering sharing her story. In 2020, she shared a short poem she’d written about Keenan anonymously in a stage presentation at the local Playhouse Theatre. Then, in a recent conversation over a scone and tea in a Derry café, Cowley revealed herself as the author and opened up about her pain for the first time.

Cowley grew up in a Catholic family in Derry during The Troubles, a 30-year period of violent sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland between Protestant unionists who wanted the province to remain part of the United Kingdom and Roman Catholic nationalists who wanted to be part of the republic of Ireland.

She met Keenan when they were both 16. She was studying at Thornhill Grammar School, an all-girls school in Derry, and he was at St. Columb’s College, a nearby all-boys school, she said. Over the next three years, Cowley would come to know Keenan as studious, creative and gentle.

Both Cowley and Keenan were Catholic, but the Keenans were far more active in Republican politics. While Cowley’s parents loved Keenan, they knew about his family’s radical politics and worried about her safety, she said. Keenan’s dad, Seán, was chairman of the Derry Citizens Defence Association in 1969, and would play a pivotal role in the events that led to the creation of Free Derry.

“They believed so much in a united country,” said Cowley. “My family weren’t really like that.”

While her family too hoped to see a united Ireland, they didn’t believe in going so far as to take up arms, she said.

On Sunday, January 30, 1972, violence peaked in D

erry as British paratroopers opened fire on civilians in the Catholic part of town, killing 13 and injuring 14 others. The day came to be known as Bloody Sunday, and ushered in the darkest year of the conflict — with over 450 people killed and nearly 5,000 people injured throughout Northern Ireland.

“The whole ethos of the city changed that day,” said Cowley, adding that the event led many men and women in the community to join the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

On March 14, Keenan and his best friend, Eugene McGillan, were shot by British Army patrol in the Bogside area of Derry. According to Irish news sources, both men were unarmed.

Cowley was heartbroken. The following days were hazy, but what she does remember is the tri-colored flag that was displayed at his funeral and the pain she felt piercing her heart and stomach when she saw his body, she said.

Over the coming months, her grief would lead her through some major life decisions, like applying to finish her nurse training in County Armagh, just to get out of Derry.

“I wasn’t conscious, but when I think back on it, that was the way that I survived,” she said.

As a melancholic smile stretched across her face, Cowley said life has a way of continuing. And it did for her — she became a successful nurse, married her husband Pat, moved back to Derry and raised her four children.

When Cowley mentioned Keenan in passing to her family, she said they were supportive. But she never truly revealed the impact he had on her. “I just got on with life,” she said.

In her loss and in her silence, Cowley is not alone. Although this month marks 26 years of relative peace in Northern Ireland, with the Good Friday Agreement putting an end to much of the violence in 1998, hundreds of survivors are only in recent years opening up about what they lived through during The Troubles.

Intimately involved with this process is Norma Patterson, a therapist at WAVE Trauma Center, one of the few places in Northern Ireland working specifically with survivors of The Troubles. She explained that many people keep living as if they’re still in the war because of the impact trauma has on the nervous system. But now that many survivors are older and the busyness of life has started to slow down, people have room to process.

“They can begin to think ‘okay, maybe I don’t have to just survive anymore,’” she said.

In Derry, community members have started looking to the arts as a means of healing, said Kieran Smyth, community relations officer at The Playhouse Derry.

Smyth heads a program called Leaders for Peace, designed to encourage self-care and peacebuilding strategies through storytelling. He said that while it seems counter intuitive that healing can come through reliving a traumatic experience, the opportunity to do so as means of creating art often empowers people.

In 2020, when the Irish playwright Damien Gorman came to town, several survivors had the opportunity to share their story publicly. Working with Leaders for Peace, Gorman invited anyone with an association to the year 1972 to join his new production, called “Anything Can Happen 1972: Voices from the Heart of the Troubles.”

Getting people to open up about their experiences was no easy feat; many chose to include their stories on the condition of anonymity. Actor Pat Lynch played the role of The Caretaker, a narrator-type character who showed up multiple times throughout the play to perform anonymous stories.

At that time, Christine Cowley was one of the people who chose to have her poem performed by Lynch. Her poem was about a moment when she thought she saw her lost love, Keenan, and even though she had spoken about it to her family before, she still felt strange sharing about it publicly, even under the cloak of anonymity. At one point, Cowley almost pulled her submission entirely.

“After this length of time of being married to my husband, I felt it was disloyal,” she said.

Cowley said that Gorman encouraged her to tell the story, and her husband thought it was a nice story. In September, the production opened. It was broadcast to the public because of the pandemic. Cowley only saw it once, surrounded by a group of her closest girlfriends.

“Most of the words I didn’t hear. It was weird to hear someone else read my words,” she said.

Nearly four years after the production, Cowley’s feelings about sharing her story have changed. In recent months, it had been on her mind to own those words, she said.

She said she’d encountered angels throughout her life in different people, and some of her more recent supernatural-feeling encounters emboldened her to tell her story as her own.

“I love the concept of angels,” Cowley said from her table at the café. “For me, they’re guides.”

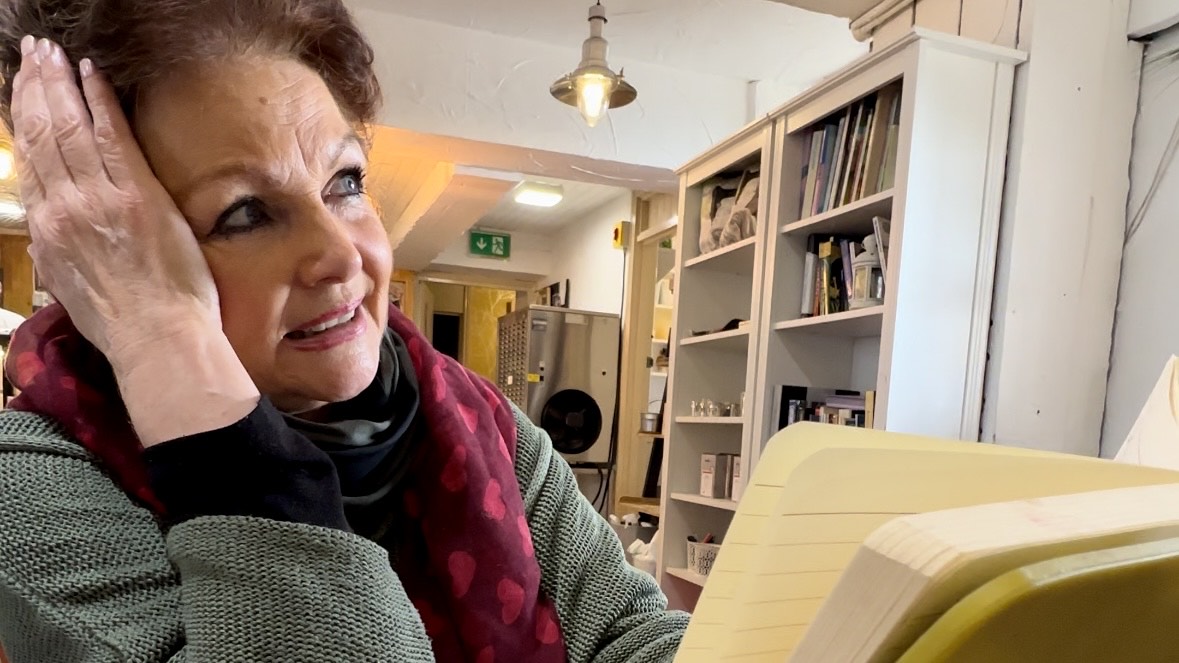

With steady hands, Cowley flipped to a page in a bright yellow notebook where she’d written the poem four years ago. At first, she was timid, realizing that in the busy café in a town as small as Derry, she could run into anyone she knew. She put one hand over the side of her face and began reading with a tension in her voice:

“Did you just walk by me then

In the daylight

Or was that a dream

My heart surged with sadness

Tears ran down my cheeks

At the vision I had just seen.

Please, oh please, look over here.

This yearning is unreal

Your hair, your body

Your clothes the same!

My mouth wide open, to call your name”

Cowley moved her hand away from her face and continued, but this time, with a softened voice:

“You turned my love

Your loving eyes met mine

They melted like snow

Through my body

To stay with me for all time”

At the end of her poem, she lifted her teary eyes from the page, coming out of her trance.

“It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” she concluded. “It’s actually something to be very proud of, but it’s taken a long time to come out.”