Dharma Wisdom: Lessons From Zen Mountain Monastery

SHANDAKEN, N.Y. — On a recent Sunday morning at the Zen Mountain Monastery — nestled in the Catskill Mountains — more than a hundred worshippers gather for a service of chanting and meditation. Light floods through the windows of the lofted wooden room, illuminating the space. After two hours of chanting liturgy and sitting in Zazen meditation, the congregation stretches and shakes out their limbs before settling back down on their zabutons — cushioned mats. Some are crossed-legged, while others sit on their feet; all are turned towards the altar, prepared to receive the spiritual teaching known as the Dharma talk.

A man in a white robe — indicating his status as a senior student — walks down the aisle and approaches the altar. He performs a series of ritual bows, walks clockwise around his mat, and sits with his legs crossed. Then, a Buddhist priest walks down the aisle with a small lectern draped with a blue cloth and places it before him. The man unfolds the cloth to reveal a small notebook and reaches for a lavalier mic stowed beneath his mat. He clips the mic to his lapel, takes a deep breath, and presses his palms together, offering a gassho — a bow with hands in a prayer position — as an offering to the congregation and a sign that he's ready to begin his teaching.

A Buddhist priest in the corner of the room taps the rim of a large singing bowl three times, and the congregation begins to chant the names of the four bodhisattvas — enlightened beings who vowed to remain in the world to guide others, embodying central virtues such as compassion and wisdom that practitioners hope to cultivate.

In Buddhism, a Dharma talk is public discourse, given by a teacher or senior student, with the intention of providing practical wisdom about the practice. It is casual, with a conversational style, and has witticisms sprinkled throughout. It seems to balance the delight and discomfort of the practice perfectly, holding space for suffering while allowing joy to float to the surface.

On most Sundays at Zen Mountain, the Dharma talk is given by Sansho — the abbot of the Monastery — but he wasn't feeling well and asked Gikon — the man in the white robe — to fill in. Gikon opened by acknowledging his fear and anxiety, calling out his perfectionism and admitting that part of him didn't want to be giving this talk at all.

“The Buddhist teachings are often talked about like they're a raft,” Gikon said, “but for me, they are more like a life preserver.” He went on to give a testimony of his journey with the practice, starting with the first Buddhist teaching he read while in graduate school for social work. He learned that the ways we try to make sense of our lives are flawed. All of the great achievements that we value — philosophy, psychology, literature, art — take place just on the surface level of the mind and are therefore shallow pursuits. That was not what Gikon wanted to hear. At that point in his life, he had devoted himself to higher education — winning philosophy awards and studying the great poets. He had been in a desperate pursuit of something bigger, some undeniable truth that could give his life meaning. But when he read that first teaching, he realized there was something missing in his life and he turned to Buddhism.

The talk feels like a conversation. The congregation is deeply engaged, quick to laughter and hems and haws — vocal affirmations of a shared experience. Gikon speaks candidly about his fear and his daily struggle to go within. All the ways he used his mind to beat on his mind, in a failed attempt at mindfulness—or maybe control.

He encourages the congregation to sit with their fear, using it as a starting point to go deeper, through all their underlying assumptions, to the root of their suffering — the seed through which the fear was planted. Gikon credits the practice of Zazen — seated meditation — for changing his life and then presses his palms together, in one last gassho, indicating the end of his Dharma talk.

Rhythms of Reverence: Chanting and Meditation at Fire Lotus Temple

NEW YORK — On a recent Sunday morning, amid intermittent rain, worshippers leapt around growing puddles on the sidewalk outside Fire Lotus Temple in Brooklyn before entering through the large wooden doors. Located on the corner of Third Avenue and State Street in Park Slope, the temple’s aged brick facade and wooden placards stood out among the surrounding residential buildings. Upon entering the temple, the smell of incense greeted each visitor, inviting them into the sanctuary. One by one, people lined up in the vestibule, waiting to bow at the altar inside the temple to clear and purify their minds before crossing the threshold and entering the sacred space.

The sanctuary was a large room with low ceilings. There were 40 meditation mats, spaced out in even rows on the floor in front of the temple’s altar. Mara Leighton, a Brooklyn native dressed in navy sweats with her long brown hair thrown into a messy bun, entered the sanctuary minutes before the service began. She found a meditation cushion to her liking, and sat cross-legged, closing her eyes, taking a deep breath and settling into her mat.

After an opening procession and a series of bows, a Buddhist priest handed out liturgy books before taking a seat at the front of the room next to two large singing bowls. These bronze bowls—when gently struck or played with a mallet—produce rich, resonant tones that support the chanting by setting the rhythm and creating a meditative atmosphere. Everyone opened their books to page three, "The Heart Sutra." The priest scanned the room, waiting for everyone to settle before picking up a wooden mallet and slowly tracing the rim on the bowl three times. As the third ring started to fade, another priest made his way to a large bronze gong, or kesu, sitting in the back corner of the room. There was a brief pause, and then the priest struck the gong.

BONG.

The sound echoed through the sanctuary, and the head priest stood and chanted, “Maha Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra.” Then a third priest picked up a mallet and started banging a wooden drum carved like a fish holding a pearl in its mouth.

BOOM. BOOM. BOOM.

There was a moment of silence, and then the congregation joined in with “Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, doing deep Prajna Paramita,” spoken in traditional Sanskrit. The loud, rhythmic beats reverberated through the room. Even standing on thick mats, you still could feel the vibrations in your feet. Leighton stood, with her sock feet balancing half on her mat, glancing around the room, doing her best to pronounce the foreign lyrics. The chants got a little louder during the English verses, “Form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form. Sensation, conception, discrimination, awareness are likewise like this.”

The Heart Sutra is the most popular sutra, or sacred teaching, in Mahāyāna Buddhism. Every morning, Buddhists around the world chant this sutra together as a reminder that form is an illusion. The Sutra goes through five skandhas, or the mental factors responsible for the rise of craving and clinging: form, sensations, perception, formations, and consciousness. The lyrics encourage Buddhists to release association with form to connect with a higher realm. But the chanting is not about the lyrics; it’s an invitation to allow the practice to carry them beyond wisdom, towards “wisdom beyond wisdom,” to a far shore of awakening that exists beyond suffering.

The resonant sounds filled the air, pulsing vibrations swirled through the sanctuary. Everyone chanted in unison, “Far beyond deluded thoughts; this is Nirvana.” As they chanted the final words of the Heart Sutra, translated as "Gone, gone, everyone gone to the other shore, awakening, svaha, the perfection of wisdom,” all the voices funneled together in a deep monotoned decrescendo, ending in abrupt silence.

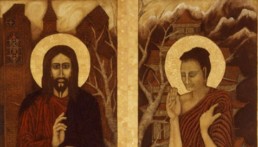

A Life of Double-Belonging: Some Religious Leaders Practice Two Faiths

In a dimly lit Roman Catholic church on a recent Monday night in Manhattan, around a dozen congregants sit in the pews watching the Rev. Michael Holleran as he leads them in what is known as contemplative prayer. During this kind of prayer, one word of the congregant's choosing is silently repeated over and over again. There is some singing, and some prayers said aloud throughout the hour-and-a-half-long worship. Every so often Holleran rings a bell three times, which is meant to awaken worshipers from “sleep and into a consciousness of God’s presence.” This form of prayer is often compared to meditation due to the silent repetition of one word and the focus required. Peace, love, truth; these are just a few of the word choices worshipers might repeat. If their mind wanders, they are instructed to return to the word.

Contemplative prayer was adopted by some Catholics in the 1970s and takes inspiration from faiths like Buddhism, so it’s no wonder that in addition to being a Catholic Priest, Michael Holleran is also a Buddhist Sensei.

Michael Holleran serves as the priest at the Church of Notre Dame, a Catholic church in Morningside Heights, but once a week he leads a Buddhist Zen Meditation session over Zoom. He practices double-belonging, a term coined in 2009 by Paul Knitter who wrote a book titled “Without Buddha, I Could Not Be a Christian.” Knitter is a major influence on many Catholics who subscribe to Buddhist ideology. He insists the two faiths do not conflict with one another. The teachings in his book have spread to some, including professors of religion like Chad Thralls of Seton Hall University and Catholic priests like Robert Kennedy, based in New Jersey. They too have followed a life of double-belonging as outlined in Knitter’s book.

Buddhism and Catholicism have been compared to one another in the past. In 1870, The Atlantic, an American magazine that was first published in 1857, reported on the similarities between the two faiths. “The Tibetan lama listened respectfully to the Jesuit priest and replied, ‘Your religion is the same as ours,’” reported Lydia Maria Child.

Buddhism originated around 1,500 years ago. Founded by Siddhartha Gautama the faith spread from India to the rest of Asia and eventually the world. In the tradition life is seen as a cycle, entailing suffering and rebirth. Finally, one can achieve enlightenment and break the cycle. Catholicism traces its roots to Palestine in 30 CE following the teachings of Jesus Christ. Catholics believe that if you confess your sins and base your life around the 10 Commandments you’ll go to Heaven after you die. Some Catholic theologians insist that the two faiths do not conflict, but in fact, build on one another.

As Holleran has explored his religious identity, he says he has found a “vibrant synthesis” between Buddhism and Catholicism.

“I don't see any conflict among any of these traditions,” he said. “If you're actually going deep enough into what they're really all about, that is to say, finding union with God, making the world a better place, transformation of your own consciousness, etc.”

For Holleran, this approach is specific to Catholicism and Buddhism and doesn’t necessarily extend to other faiths like Judaism and Christianity. A joint practice of those faiths might be harder to fit into the double-belonging theme.

Raised as a Roman Catholic, Holleran, 72, joined the Jesuits at Fordham University, where he took a course in various religions and learned about Buddhism. Holleran eventually became a Carthusian Monk in France, a contemplative order. Today, as the priest at the Church of Notre Dame, he keeps his two faiths separate, that is until he leads the Dragon’s Eye Zendo Wednesdays on Zoom. During Zen meditations, Holleran mentions Catholic scripture or figures but doesn’t mention Buddhism during Catholic services. Some people attend both the contemplative prayer and the Zen meditation each week like Chad Thralls.

Professor Thralls, who teaches at Seton Hall University, a Catholic institution, says that many of his students are excited to learn about faiths other than Catholicism. Therefore, whenever he involves Buddhism in his coursework, students are engaged. Holleran and Thralls cite theologian Paul Knitter as a source of inspiration in their journeys with double-belonging.

The Coining of the Term

Knitter, 83, began studying to be a priest in Rome during the Second Vatican Council, a major reexamination of Catholicism that took place in the 1960s. At the time, the Catholic Church encouraged students to learn about other religions in addition to Catholicism. This started his interest in other faiths and he began to question Christianity as the “superior religion.” Eventually, this inspired Knitter to write a book about how Christianity is just one of many traditions. From then on Knitter said he understood Christianity from a Buddhist perspective.

“It was as if I was wearing Buddhist glasses while reading Christian texts,” he said. Knitter was ordained a Catholic priest but then left the priesthood and became a professor of theology.

Knitter has questioned whether he is Christian or Buddhist in the past. Today, he is a member of a Christian parish and a Buddhist community. On the other hand, his faith identity has been a controversial topic in the academic community. Knitter says he has faced some backlash for preaching double-belonging. Many religious scholars think you cannot be both, but Knitter disagrees.

“Religions need each other to understand themselves,” he said.

This inter-religious study is called comparative theology, and it is more broadly accepted now in mainline Christianity. Knitter suggests this is likely because of the intercultural world we currently live in. In the 1980s Knitter and his peer, John Hick proposed a pluralistic understanding of religious diversity or as Knitter puts it “a pluralistic understanding of the world's religions.”

During one of Chad Thralls’ recent lectures at Seton Hall University, he explained the first chapter in Knitter's book to the students, then asked them some questions to see what they thought of it. He references Knitter each semester he can. To a room full of undergraduate students, all raised Catholic, he presents this prompt: “In the book, Knitter notes that one of his students questioned whether he was ‘spiritually sleeping around’ by practicing both Christianity and Buddhism. Is Knitter cheating on Jesus?” During that class discussion, Thralls says none of his students believed Knitter was.

Not every Catholic is on board with double-belonging and the ability to whole-heartedly practice two faiths. Another Catholic priest, the Rev. John D. Dreher, was outspoken about the matter in an article for Catholic.com. For him, the two are incompatible.

“In Catholic teaching, all men are creatures, called out of nothingness to know God. All men are also sinners, cut off from God and destined to death,” he said. “Eastern religions, in contrast, lack revelation of God as a personal Creator who radically transcends his creatures. Though possessing many praiseworthy elements, they nonetheless seek God as if he were part of the universe, rather than its Creator.”

Still, Holleran, who doesn’t mention Buddha during his Catholic services, is fairly open about his practice of both religions. His personal website plainly states his credentials as a former Carthusian Monk and Priest and as a Sensei. It also references Knitter and double belonging.

Holleran says he hasn’t received much backlash from anyone about practicing double-belonging. He continues to lead Catholic services and Zen meditations. Additionally, he gives lectures about the intersection of the two faiths to students every now and then.

Of the potential for backlash, he said “Mystics have been crucified in all traditions, not just Christian, Jewish, Muslim. They're always a problem, a danger because they challenge the limitations of the institution.”

The New York Archdiocese has not replied to repeated requests for comment about whether double belonging is something they support among their priests.

The Retreat

On April 10th and 11th, the University of Wisconsin-Madison held a retreat in which around 25 “Interfaith Fellows” from the university’s Center for Religion and Global Citizenry practiced a variety of faiths to better understand them. They met in person at Holy Wisdom Monastery, a Catholic Monastery of Benedictine nuns. During the retreat, they experienced contemplative prayer, Zen meditation, and Tibetan meditation, among other practices.

Paul Knitter was one of the event organizers. He says they focused on similarities and differences between faiths but argued that many have similar goals.

“Through the contemplative practice, we discover a larger self,” Knitter said. “We’re finding ourselves as part of a larger reality, which is called by different names. God, Nirvana, Allah, Gahe.”

Although none of the students definitely said they would practice double-belonging after the retreat, many said it was an enlightening experience.

In an ever-globalizing world, religions from the East and West build on one another, according to those who practice double-belonging. Scholarship has further spread this idea. “Without Buddha, I Could Not Be a Christian” has outsold all of Knitter’s other books. He said he gets thank you emails once a month, even now. Regardless, Knitter doesn’t think most people will ever become pluralistic in faith, but they may become more open to the idea that some are. “People might be more open to learning from others,” he said.

A version of this story has been republished by Religion News Service.

In Anxious Times, Asian Columbia Students Turn to Buddhism

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Ling Lan was thrilled when she was accepted into the highly competitive Ph.D. program in mathematics at Columbia University in 2019. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York with a vengeance. Lan’s funding was suddenly in question and she had to find a new professor who could fund her before the deadline to ensure her study.

Lan, who is 24 years old and is from China, was so anxious. The immediate lockdown made it far more difficult for her to get in touch with potential funders. She could only send cold emails to professors and might not get any responses for a long time. She was so worried; she couldn’t fall asleep at night.

As a long-time Buddhist, Lan decided to turn to the Buddhist practice of meditation to calm and release her anxieties.

“Meditation allows me to focus on the difficulty itself, without any negative emotion that might affect my thinking,” Lan said. “I sit for an incense every day, and at night I can sleep well, for I don’t have to bring too many concerns into bed.”

Lan is not the only young student who turned to Buddhism to seek emotional support. Statistics show that Buddhism is quickly gaining popularity among younger people, especially well-educated college students. According to the Pew Research Center, from 2007 to 2014, in the U.S., the Buddhists' population between 18 to 29 years old increased by 11%, from 23% to 34%, being the fastest among all age groups they’ve researched. In China, a study by Peking University points out that Buddhism has more believers under 40 years old, and tends to attract more well-educated people than other religions.

At Columbia, the Zen Buddhism Club has more than 30 students from different backgrounds who speak Mandarin. Lan serves as the founder of the club. Once every two weeks, the members gather on Zoom for a discussion under the guidance of a Buddhist teacher named Master Jiantan.

Jiantan fully converted to Buddhism a few years after finishing his Ph.D. degree at Taiwan University Department of Electrical Engineering. He became a monk at ChungTai Zen Center, one of the biggest Buddhism temples in Taiwan, and then moved to Houston, Texas to operate an affiliate. “Jiantan” is his Dharma name after he became a monk. The name means “see ephemera” in Chinese. In Buddhism, believers should all call one by his/her Dharma name after he/she got one from a monk or a temple.

He and Lan met at NYU’s Zen Buddhism club. After a few lectures, Lan followed Jiantan and went to the 7-Day Meditation event he held at his temple in Houston. The event is so focused on meditation that the faithful who gather do not speak a word or use their phones, even when they were eating and going to bed at night.

When Jiantan started to advise the Columbia Zen Buddhism Club, he gave lectures on Dharma (Buddhism rules and philosophies). However, the leaders found that the members were not as interested as they thought they would be. Therefore, Lan and Jiantan decided to change to those topics that related closely to student’s daily life, like how to deal with peer pressure, anxiety, procrastination, or why chose to go vegetarian, and analyze it from a Buddhism perspective. Since lots of members are female, Lan also designed special topics for them about appearance and body anxiety.

Jiantan, around his 40s, teaches differently here and in his temple in Houston. Compared to Columbia, believers in Houston are around 50 to 60 and has more experiences and more “results” in their life. Usually, he teaches them how to find reasons behind their already-existed “unsatisfaction” and “suffering.” At Columbia, Jiantan encourages young people to use Buddhist techniques like meditation to help them achieve success, both in academics and careers.

“We changed the topics to make it compatible with student’s life,” Jiantan said, “it’s a starting point that brings students to the town hall of Buddhism, so when they are facing challenges, they can use the principles of Dharma to deal with it, instead of having negative emotions or feeling depressed and hesitant.”

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

Besides academic and career life, young Buddhists are also exploring topics around dating and romance. Kuang Huang, 27, is one of the initial members of the club. At the beginning of the New York City lockdown, his love life fell into trouble. He didn’t tell anyone. However, one day after a regular lecture in the Buddhism club, Jiantan asked Huang how he felt about people's unhappy love life. Huang still doesn’t know how Jiantan found out about his trouble. “Probably through some of my expressions,” Huang said. “But when I actually spoke out my confusion and opinion [to another person], I felt relieved.”

To Huang, Buddhism not only taught him how to heal from a broken love relationship but also enabled him to actively strengthen his bond with his family. And that’s the main reason that prompted him to study Buddhism in the first place. Huang’s mother is a lay Buddhist in China. Initially, Huang thought Buddhism was just a way she uses to kill time and meet new people after retirement. She would go to temples and events near her home, chant with the monks there, and told her experience to Huang.

At first, Huang didn’t know what to say when she told him about her exciting new Buddhism experience. But after he started to learn Buddhism with Master Jiantan, he better understood his mother’s faith and practice. Their mother-son relationship improved. “We would talk about the books that Master Jiantan referred to during the lecture, and she would tell me what Buddhism book she was reading, and recommend them to me,” Huang said. “It’s a spiritual activity for her.”

Both Lan and Huang said the most popular topic in the Columbia club has been the negative circle of procrastination and anxiety. There were many questions for Jiantan after his lecture on that topic. Lan said she felt procrastination and anxiety were problems that everyone was facing now. “It’s not that kind of anxiety about your career or life plan for the next two years,” Lan said. “It’s happening now.”

Before the pandemic and lockdowns in New York, the club members would gather at school once a week, watching Jiantan’s live lecture on the big screen together in a classroom, meditate and chant with him. After the lecture, the club members would stick around for a while, share snacks and talking to each other. The club would also hold dumplings-making events during the Chinese spring festival.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club

However, soon after the club’s event schedule got stable, the pandemic began. For the past year, members can only attend the lectures from their own homes through zoom meetings. But still, though physically distanced, the similar problem, choices, and ethnicity of its members made the club a “safe zone” for Chinese international students. It is a place where they have the chance to speak a familiar language, and address their confusion to a familiar crowd. “I feel a sense of involvement when we all have the same confusion,” Lan said. “We are a group. And then when Master Jiantan started to lecture on it, we would have a better understanding of what he said.”

At the end of each lecture, Jiantan leads students in a meditation. “Meditation helped to relieve our worries [towards our safety]”, Huang said referring to the recent spate of anti-Asian hate crimes. He explained that “the heart of compassion” is important for Buddhists, and protecting oneself is actually saving others, for “you won’t give others the chance to hurt you and thus do evil,” Huang said.

Lan noted that her fellow Columbia students have different concerns than their parents back in China. The older generation might wish for a stable life, for they’ve been through starving or social turbulence. While the younger Buddhists usually have a better material life, they might live with bigger mental pressure.

“Each generation has its own characteristics when studying Buddhism due to the era they grew up in,” Lan said.

But in Buddhism, their final destination might be the same.

Photo courtesy: Columbia University Zen Buddhism Club